Each Monday morning, VOA’s features staff gathers to rattle off the compelling stories on which we’re working or hope to work at some point in our lives.

When it was my turn last week, I mentioned that I was going to write about the wrenching, sometimes scary, process of examining one’s own life through words and then sharing this memoir with the world.

As I spoke I could not help but observe a startled look and arched eyebrow on the face of one of our editors. Not a skeptical arch. A knowing one. It signaled that she knew all too well of what I spoke.

Especially the scary part.

Jane Friedman then disclosed that she, herself, has been writing a memoir, in fits and starts, lo these many years. After some cajoling on my part and much mulling on hers, she agreed to share not only some insights from her journey of self-exploration, but even a few excerpts of the incomplete results.

The book-in-progress is called The Diamond Dealer’s Daughter, with the subtitle, Escaping 47th Street Through a Life in Journalism.

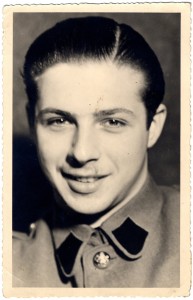

Willem Friedman had been a conscript in the Belgian Army. He became a prisoner of war but was released by the Germans. Willem made his way to Free France and Marseilles, where the Belgian consulate drew up papers that helped him finesse his way to a reunion with other Belgian Jews in Portugal. (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

That’s 47th Street in Manhattan, the center of New York’s Diamond District, where her father, Willem, cut and sold diamonds for half a century after a harrowing escape from his native Belgium through Nazi-occupied France and fascist Spain into Portugal in 1940.

Jane is our cultural-affairs editor. She hones my colleagues’ stories about the arts, movies, and other matters related to human imagination and skill.

She has worked for other prestigious news organizations besides VOA, including Newsweek magazine and CNN, in exotic posts such as Paris, Jerusalem, Beirut, and Cairo. In the last of these, she was the first Jewish woman to head the bureau of a leading news organization.

Jane is white. Her former husband is black. And Egyptian. And Muslim. That’s just the beginning of her yeasty memoir material.

In her manuscript, she writes:

I married Aziz in a grubby Egyptian government office, his relatives snapping away. We were next after the aging Saudi in a long white robe and keffiyah with his 16-year-old peasant bride, who he obviously had paid for.

Jane had thought back to her unprincesslike wedding ceremony while sitting in a different grungy room at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, where agents had pulled aside several Third Worlders — and New York-born Jane — for closer customs inspection. She was returning to the United States with Aziz and their two children.

“I was home,” as she puts it, “after seventeen long years and four presidencies.”

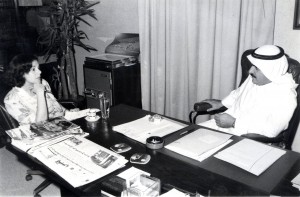

Jane interviews a prominent Kuwaiti newspaper editor in 1984, during the 'Tanker War' in the Gulf. 'Kuwait was difficult,' Jane writes. 'No drink. Very hot. And very government controlled.' (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

At the beginning of my self-decreed exile, I had set off for France, believing that, because my family was French-speaking, I belonged there. After seven years as a journalist in Paris, and my fill of left-wing intellectuals discussing nouvelle cuisine at cocktail parties, I moved to Israel. Four years in the holy land, again as a journalist, taught me that, although Jewish, I wouldn’t parlay that identity into an Israeli one. The Israelis were tough, brusk and nosy, and the nation had lost it moral compass. It was not the light unto the nations that [Israeli Prime Minister Menachem] Begin said it was.

Jane says that among the toughest stories for her to tell are her recollections of her young life as a sheltered child in a Jewish neighborhood on New York’s Long Island.

Sheltered, she says, because her mother, Helene — pronounced “el-ENN” in the elegant French fashion — who coincidentally had also fled Belgium but had not yet married Jane’s father-to-be, thought of herself as a refined European in a culture of unsophisticated, loose-living Americans. She kept herself and her daughter dressed to the nines and did not want Jane associating much with the casual, carefree urchins around her.

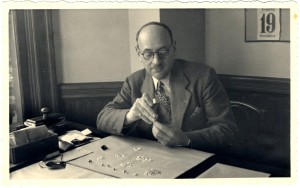

Marcel Ginsburg, Jane's grandfather, sorts diamonds. The diamond business goes back many generations in her family, to Antwerp and beyond. (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

Jane was cloistered in, as she puts it, the “Belgian Jewish bubble.” It was bilingual and intellectually stimulating thanks to her father, a voracious reader and student of history. But bubbles can be lonely places when you see all the fun that people outside are having.

One cannot minimize the impact of such emotional tyranny on an impressionable little girl. Jane describes it starkly: It was “a ghetto existence that led to my escape into journalism.”

Since she is extremely sensitive and perceptive, I was surprised to learn that Jane finds writing with emotion to be the most difficult part of the memoir chore. But her explanation makes sense: “It’s because I am trained as a journalist — detached. Writing about yourself, your family and friends, and your life, you have to write about feelings, write WITH feelings.”

“This does not come naturally to me,” Jane admits. And she’s a ruthless critic of her own work. “It’s only enjoyable if I see something I’ve written that I like,” she says. “So far, that’s not frequent.”

At last back in what she describes as “home sweet American home” in 1990, Jane and her family settled in a furnished apartment in Falls Church, a leafy Virginia suburb of Washington. “I spied a yellow school bus,” she writes, “and at the sight of something so familiar, so quintessentially American, so wrought up with my childhood, I began to cry.

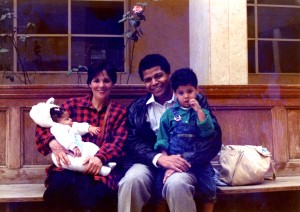

Jane, her husband Aziz Fahmy, and their two children, Ines and Adam, in happier days in Cairo in 1989. (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

After long years, I was back. My family — my father, my brother and uncle, Jews originally from Belgium — were nearby in New York. My brother had encouraged me to return and rejoin the family.

The career stuff was a snap to write about, she says. But she turned out those chapters years ago. With a fresh eye, she finds that they need work. Jane is an editor, and thus a perfectionist, after all. She’s toughest on herself. “You keep evolving as a person,” she realized. “You look back at what you’ve written and are certain that some things need to be recast.”

“That is the problem with a memoir,” Jane says. One of them, anyway.

A part of her manuscript that she calls her “France chapter” tells the story of a memorable “get,” as we say in the journalism game — an unforgettable interview with an elusive subject.

Shown here soon after she'd been named CNN bureau chief in Cairo in 1984, Jane looks confident and content. (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

Jane had already scored plenty of them as a Newsweek correspondent in Paris, including fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent and the philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. And a few years later, she would interview some of the men who had, in Jane’s words, “stormed the barricades” in a student revolt 10 years earlier but had turned “paunchy and disillusioned.” It gave her what she calls “an understanding of the post-’68 malaise.”

The crowning scoop involved an encounter with Eldridge Cleaver, the Black Panther militant who was on the FBI’s most-wanted list and had fled the United States after exchanging gunfire with police in California. After stops in Cuba and Algeria, he was welcomed into France on, as Jane writes, “one condition: he had to be politically invisible.”

Circumspect with the media, too. But having heard that Cleaver hung out at the Shakespeare Book Company on what Jane calls “the funky Left Bank” of the River Seine, she left a scrap of paper for him there, with an interview request and her phone number.

About six months later, she relates in her manuscript, “my telephone rang. ‘Mademoiselle Friedman, s’il vous plait,’ said a man with a deep voice in a heavy American accent. I could feel my heart racing, with both excitement and fear.”

Jane Friedman and Eldridge Cleaver look over something, perhaps a scrapbook, at his apartment in a working-class neighborhood of Paris. (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

An interview was arranged in Cleaver’s loft apartment. Speaking, rather bizarrely, from a red-leather dentist’s chair, he told Jane that he was ready to — wanted to, actually — return to the United States and face charges.

“With his two children scampering around, and with Panther memorabilia plastered on the walls like posters of rock stars in a teenager’s bedroom,” Jane writes . . .

. . . he said his journey though the largely “socialist” developing world had taught him that there was a “cultural chasm” between Black Africa and African-Americans. He said he had renounced political violence and wanted to settle in California where “people have the room to be human.”

Cleaver was apparently not in a terrible rush to leave Paris, however, for Jane writes that after her story hit the wires and newsstands “Eldridge and [his wife] Kathleen quickly became the toast of the town in what became the Paris version of radical chic.”

A few months later, Cleaver appeared before a phalanx of microphones and photographers and announced that a deal had been brokered that would allow his return to the United States. Here, he pleaded guilty to an assault charge in return for probation rather than jail time. He became a devout Christian; published his own memoir, Soul on Fire; and, in 1998, died of undisclosed causes — perhaps the diabetes or prostate cancer from which he was reported to be suffering.

Telling this and the rest of her story, Jane Friedman was inspired by Suzannah Lessard, who now teaches a Master of Fine Arts writing course at Goucher College in Baltimore. Some years ago, Jane had earned a fellowship that gained her entry into another of Lessard’s creative-writing workshops at George Washington University in Washington, and the experienced writer became her beau ideal.

Lessard had written her own highly charged family story, The Architect of Desire: Beauty and Danger in the Stanford White Family. As one review put it, White was “Suzannah Lessard’s great-grandfather [and a] prominent architect, socialite, and hedonist who was murdered by the husband of a showgirl White had seduced when she was 16.”

Talk about fodder for a memoir!

I reached Lessard between classes. She told me that memoir writing is surprisingly “hospitable” to novice writers because they know the material so intimately. But, she says, it requires understanding and guidance to organize that material and to come to grips with what is often a “deeply emotional psychic struggle to deal with areas of family life that may have been excluded from consciousness.”

Memoirs are not for dilettantes, Lessard warns her students, since they are bound to “shed light on others’ private lives as well as their own.” This does not always go over well.

That may not be a problem in Jane Friedman’s case, however. “I believe it will be helpful for my kids — and also my relatives — in understanding the past of our families and why things happened the way they did,” she told me. “My cousins are very interested in seeing this manuscript because they grew up exactly like I did.”

The most satisfying aspect “is that I’ve been able to see the broad strokes of my life, not just the events,” Jane says. “It has helped me understand what my life has been about, why I had — even in adulthood — the problems that I’ve had, how they go back to my parents’ escape from Europe.” And why, to use her word, her parents “brainwashed” her and her brother to live and think a certain way.

Jane was about 2 when someone snapped this photo of her and her dad on the boardwalk at Atlantic City, New Jersey. A little later in her life, he interested her in history and politics, and they watched shows such as 'You Are There,' which included historical re-enactments. (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

So Jane figures the memoir “has been instrumental in helping me get myself together, as they say.”

She has set 2013 as a target date for completion. “Enough is enough,” she laughs. Once again she will seek a coach — another author whom she met at a workshop. And probably a spot in another seminar, at the Writer’s Center in Maryland, “so I’ll have deadlines.”

Why all the mentors and seminars for someone who is already an accomplished writer? “Insecurity, of course,” Jane answered. “Not in writing about my journalistic exploits but about my childhood, the way I was brought up. There is so much. What to cull, how to organize it, not to go into unnecessary detail, how to build characters so they’re understood.”

Indeed, unlike memoirists, journalists don’t have to start from scratch. The pieces of their stories are laid out before them, ready to be assembled.

Suzannah Lessard was especially helpful in making the daunting task manageable, Jane says. “She helped us all with structuring, what should be in the memoir, what does not belong. Where a memoir should start and where it should end. What should be in a basket of sorts, a subchapter. How to lead so the reader understands what’s going on. Legal issues with memoirs. We wrote and wrote and critiqued each other’s writing.”

Jane says she is not much interested in walking through the minefield of rejections that typically accompanies a search for an agent and a publisher. Some of her friends have found satisfaction and success in self-publishing, she found, thanks to the Internet revolution and a flourishing market for “e-book” memoirs.

Perhaps fortuitously for Jane, Suzannah Lessard told me that the spike in interest in memoirs has coincided with a burst of women’s accounts of their lives that have been critically acclaimed and snapped up by readers — other women in particular.

Biographies had been mostly about famous men, she reminded me. Suddenly, “ordinary women’s life stories were coming out of the shadows and into the light.”

As for a timeline, Jane Friedman’s narrative in The Diamond Dealer’s Daughter ends in 1999, two years after she and her husband separated. They would divorce nine years later.

She told me that the story of what had changed between them, and what led to the dissolution of their marriage, is one of those toughies that, she figures, “I guess I’ll have to deal with” in the manuscript before putting her memoir to bed.

I saved this photo of Jane for last. I think it says something, something quite nice, about her and her memorable life of adventure. (courtesy, Jane Friedman)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Beau ideal. A person who represents the highest standard. An exemplar or role model.

Dilettante. Someone who flits from subject to subject or activity to activity without putting a lot of effort into any of them.

Dressed to the nines. This is thought to be a corruption of the Old English “to the eyne,” or eye. So you’re dressed to the eyes. “All dolled up” is another way of putting it.

Nouvelle cuisine. Fresh, light, usually French food, contrasted to classic French dishes that are buried in sauces.

Urchin. A street kid, usually dressed raggedly.

One response to “More On Memoirs”

Awesome blog article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.