Could it be that parochial Fluffya is changing?

Who would have thought that after more than three centuries of mostly minding its own business, the hard-working city of narrow streets, grimy factories, and quaint colonial buildings in the southeastern corner of Pennsylvania would be transformed into one of America’s most dynamic and appealing tourist destinations.

“Fluffya?” you’re saying. “I’ve never even heard of the place.”

Yes, almost certainly, you have. You’ve spelled and pronounced it “Philadelphia.” “Fluffya,” is how the locals say it — especially those in South Philly and Senda Siddy. (That’s Fluffians’ twist on their term for downtown, their Center City.)

Philadelphia at nightfall. (Carol M. Highsmith)

In deference to the historical significance of the place, I’ll mostly refer to the nation’s fifth-largest city as “Philadelphia” from now on.

But I wanted you to know that the wellspring of our democracy is both an intellectual university town and a blue-collar community where people consider long, thick cheesesteak sandwiches and Tastykake snack cakes delicacies, where they will stand for hours in snow or biting rain to watch “mummers” cavort on New Year’s Day, and where they root, fiercely and often quite rudely, for their Iggles.

Iggles: the Philadelphia Eagles American football team. Rudely — drenching opposing teams in boos and curses and, from time to time, any of those teams’ fans who dare show up with beer. Philadelphia has never lived down the day, 44 years ago, that Iggle fans booed, and threw snowballs at, Santa Claus.

This, in a place whose name, taken directly from the Greek, means “brotherly love.”

I should explain “mummers,” in the event you missed my posting a year ago January, after I returned, gushing with appreciation, from the Mummers Parade.

Mummers are masked and elaborately costumed frolickers who dance and sing, play the lowly kazoo — which sounds like one of those little noisemakers that kids blow at birthday parties — and choreograph amazingly intricate spectacles — right on the city’s main streets.

The comic brigades sashay before the crowd in incredibly lavish costumes, often lugging their own backdrops, while poking fun at politicians, issues in the news, and economic vagaries. Last year, for instance, the Goodtimers Club presented a riff on an insect scare at the time, called “Bed Bugs on Broad Street.”

To illustrate how far from snootiness Philadelphia has fallen since the days when the country was founded there 236 years ago, the Mummers’ “wench division” — a madcap collection of hairy men in dresses, bonnets, accessory bags, bloomers, and excessive makeup — parades in spray-painted sneakers. A far cry from “dem golden slippers” for which the mummers are famous.

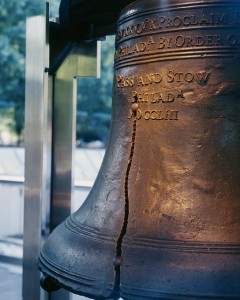

The Liberty Bell cracked almost as soon as it arrived in town, in the 1750s, long before bells all over Philadelphia pealed to celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Anyone who visited the nation’s birthplace 25 years ago or so, perhaps to see Independence Hall — where the Declaration of Independence was adopted on July 4, 1776 — and the famous, cracked Liberty Bell that hailed that dramatic event four days later when it was announced, would hardly recognize the town. Invigorated by a sleek new skyline and revitalized waterfront, an exploding arts scene, and a profusion of renowned restaurants, clubs, and sporting events, Philadelphia has shed what had been almost an inferiority complex and blossomed into what some have called the “Paris of America.”

And why not? Its tree-lined, flag-festooned Benjamin Franklin Parkway, connecting City Hall to the Philadelphia Museum of Art — with the Rodin Museum and one of seven copies of Auguste Rodin’s famous The Thinker statues midway — was designed by French landscape architect Jacques Greber with the Champs Elysées in mind.

What Paris does not have that Philly does, however, is a sizable, rundown, largely African-American ghetto as well.

Although the birthplace of the United States grew to become the nation’s greatest manufacturing center, Philadelphia was often overlooked in the roll call of important American cities. Part of the reason was its proximity to New York, only 130 km (81 miles) away. New York had a bigger harbor right on the ocean, and soaring skyscrapers, at a time when a gentleman’s agreement kept Philadelphia buildings lower than “Billy Penn’s hat” atop City Hall. The “Big Apple” was also a media and public-relations juggernaut with a much stronger penchant for self-promotion.

That's Billy Penn (or rather his bronze likeness) atop ornate Philadlephia City Hall. (Carol M. Highsmith)

“Billy Penn,” if you’re wondering, is William Penn, the Quaker immigrant who founded both Pennsylvania and Philadelphia. A bronze statue of him stands atop the City Hall tower.

Philadelphia was, in fact as well as name, “the Quaker City”: a historical curiosity whose introversion and dislike of ostentation traced to its modest Quaker roots. No one should stand out, so Philadelphia did not try. Then, as it grew bigger and bolder in the 20th Century, its reputation as a gruff blue-collar town held it back. Word of the city’s incredible cultural diversity and educational resources — there are 17 four-year colleges inside its city limits — did not always spread beyond the adjacent Delaware River.

“We arrived in Philadelphia on Sunday,” veteran broadcast journalist Jack Smith once observed, “but it wasn’t open.” Cranky stage and film comic W.C. Fields suggested as his epitaph, “On the whole, I’d rather be in Philadelphia,” meaning that even a stay in the plebian city he had often made fun of in his vaudeville routines beat the alternative he’d be facing on his deathbed.

The Ryerrs Victorian mansion was built in Philadelphia's fancy Fox Chase neighborhood. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Because many of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods had once been independent towns — with distinct industries, ethnic makeup, even accents and expressions — its politicians perfected ward politics and rarely cared what the outside world thought about the city’s affairs. Many important political and business decisions were finalized over cigars and brandy at private clubs. Writer John Gunther called city leaders “an oligarchy more compact and more entrenched than any in the United States.”

It was Philadelphia, for instance, that elected its gruff, bombastic police commissioner, Frank Rizzo, as mayor twice in the 1970s. He told reporters, dignitaries — even church and ethnic leaders — what he thought of them, in clear, often profane, terms — and was proud of it.

A lot of Fluffians were proud of it, too.

No one seemed to hurry much there; projects such as a new city hall or performing-arts center would often take 20 or more years just to agree upon and get going, let alone build. So the end product sometimes seemed old-fashioned the day it opened.

Swedes and Finns, then Dutch, among European newcomers to North America, first settled the area in the 1640s. But the English soon booted them out. On March 14, 1681, Britain’s King Charles granted most of what is today Pennsylvania to William Penn in payment of a large debt owed to Penn’s father by the Duke of York.

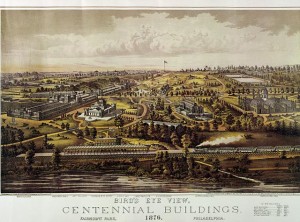

This poster from the 1876 world's fair celebrating America's centennial shows the city quite a few decades after Billy Penn lived there. (Library of Congress)

Penn journeyed to “Pennsylvania” — Penn’s Woods — only twice, staying two years during his longest visit. He actively advertised for colonists in England, Holland, and Germany, and he soon attracted a diverse mix of Quakers, Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Catholics. Even Jews, who were shunned in many other colonies. Although its harbor was far up the Delaware, Philadelphia prospered as an entrepôt for timber, furs, and farm products from the fertile Pennsylvania countryside. And because Penn actively recruited shipbuilders, glassmakers, wheelwrights, and silversmiths, skilled crafts got a strong foothold in the city.

It wouldn’t be long before refineries, breweries, mills, and other heavy industries and their belching smokestacks followed.

Benjamin Franklin, a brilliant and eccentric inventor, publisher, scientist, diplomat and wit, moved to Philly from Boston in 1723 at age 17 to work as a journeyman printer. Franklin then dominated the scene for 60 years. He was the city postmaster and founder of the college that became the Ivy League’s University of Pennsylvania. In his bicentennial history of Pennsylvania, Thomas Cochran noted that Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack, which he edited under a pseudonym, reached a circulation of 10,000 and became, “next to the Bible, the most universally seen book in the colonies.”

This statue of Benjamin Franklin at the school he founded — the University of Pennsylvania, which, with 23,000 academics and workers, is Philadelphia's largest employer. (Carol M. Highsmith)

It was the droll Franklin who, when John Hancock urged unanimous adoption of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence in 1776, signaled his agreement to the assembled Continental Congress by saying, “We must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

It was not just a metaphor. For more than a year, British soldiers with ample muskets and powder had taken active exception to the colonists’ notion of independence in battles throughout the Northeast.

At the moment that the nation’s founders scribbled their names on the Declaration, Philadelphia was the second-largest English-speaking city in the world (to London), and the leading city in Britain’s worldwide colonial empire.

Bet you didn’t know that; I didn’t.

The winning colonists returned to Philadelphia to draft the nation’s constitution in 1787, and two years later moved the capital from New York City to Philadelphia, just in time for newcomers to face a terrible yellow-fever epidemic that killed one-tenth of the population. Philly remained the capital until 1800 when the virtually new city of Washington, D.C., opened to federal business.

New York overtook Philadelphia as the nation’s largest and most dominant city soon thereafter. It benefitted from it deep-water port and location at the mouth of the Hudson River, down which goods from the heartland flowed after traversing the bustling Erie Canal. Philadelphia responded by extending the Pennsylvania Railroad through the Allegheny Mountains, but New York countered with the westward extension of the New York Central.

Still, Philadelphia evolved industrially to become “The Workshop of the World.” It eventually formed the nucleus of America’s textile, apparel, machining, furniture, boiler, and shipbuilding industries — the hub of the Industrial Revolution.

Saws, gears, rugs, streetcars, women’s hose, and handbags by the millions — and uncounted tons of sugar and flour — poured out of 20,000 Philadelphia plants and mills. The giant Baldwin Works turned out thousands of locomotives right in Center City, and the whole town was blanketed in black soot.

Immigrants poured in from Italy, Poland, and Russia, settling along the Delaware River and in outlying neighborhoods. Once the breadwinner was employed, some families rarely left their neighborhoods. Why should they? The job was nearby, the language of the Old Country was spoken on the streets and in churches and pool halls, and even the newspapers were in German or Polish, Yiddish or Italian.

But universally understood expressions took shape. “Yo,” for instance, is still the all-purpose “naydiv tawk,” as Philadelphia columnist Clark DeLeon called it. “It’s more than an accent; it’s an attitude,” he wrote. “Or as we pronounce it, ‘attytood.’”

If you’re heading to Fluffya, other DeLeon translations might be of assistance:

Kwawfee. “The liquid stuff that keeps cab drivers going.”

Purdy. “The view of the Senda Siddy skyline out the windas.”

Youze. “Second person, singular,” as in “Where youze goin’?”

South Philadelphia, with its five-block-long Italian Market full of fresh produce, cheeses, fish and squid, skinned rabbits, and a hundred other delicacies, remains Fluffya’s most distinctive neighborhood.

It has its stereotypes, which author Murray Durbin calls “13-year-old girls with big hair or tough guys in tee-shirts named Tony.” And it’s from South Philly that the mummers march to Senda Siddy.

Literally hundreds of thousands of two- and three-story row houses appeared in South Philly and elsewhere across the city. Politicians and the city’s strong unions worked to see that everyone who wanted one had a good-paying job had a house to go home to.

But Philadelphia ultimately declined as an industrial center. The Great Depression of the 1930s took a terrible toll, the need for steam locomotives vanished, and after World War II the Navy stopped ordering many ships.

But it wouldn’t be the brunt of an old joke — “What’s the difference between Philadelphia and yogurt? Yogurt has culture.” — for long. New concert halls and museums turned South Broad Street into “the Avenue of the Arts.” Proof came in 1996 when the touring Cézanne Exhibition made its only U.S. stop there. Each Spring to this day, the “Olympics of Gardening” — the Philadelphia Flower Show, attracts more than 250,000 visitors from around the world.

Fluffya is stronger and more confident than it was a half-century ago. It’s still tinkering with its mix of modern and historic, cultural and brash. But people don’t snicker so much any more when someone writes that what was once grimy Philadelphia may have become not only our “Paris,” but also — as the touchstone of our democratic ideals — “The Athens of America.”

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Entrepôt. A port where goods are imported and exported, duty-free.

Festooned. Richly adorned with decorations.

Ostentation. A lavish display, especially of one’s wealth, to impress others.

Plebian. Ordinary. The term traces to the plebes, or common people, as distinguished from wealthy patricians, in ancient Rome.

Sashay. Walk or strut in an exaggerated, ostentatious manner.