In the give and take over immigration policy in this country, it is sometimes correctly pointed out that we are all immigrants to this land. Or descendants of one. Even American Indians trace their lineage to peoples who crossed a land bridge from Asia.

The “golden door” was actually a long staircase, two rows of which, as I explain in a bit, led to a land of opportunity. The other could lead to disappointment and despair. (Carol M. Highsmith)

And at least one-third — some say 40 percent — of us are descended from someone who arrived here through a single portal: an infamous flight of stairs at a place called Ellis Island, up the Hudson River in New York Harbor.

For more than 12 million newcomers, it was their “golden door” to a new life in America.

At first, when what became a sort of polyglot city of strangers from many lands opened in 1892, the influx was a nearly unceasing flood of humanity.

Then, in 1924, almost in an instant, restrictive immigration quotas squeezed the stampede into a trickle.

Ellis was converted into a Coast Guard station and wartime detention center before being abandoned and its structures left to molder.

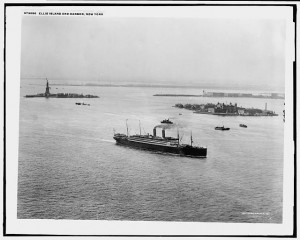

The Statue of Liberty is an ever-present symbol in the distance, beyond Ellis Island’s original administration building, right, and hospital. (Carol M. Highsmith)

But in the 1980s, a $315 million restoration project — the most ambitious in U.S. history — refurbished Ellis’s Main Building processing center as well as nearby the Statue of Liberty — that beacon of freedom that many of the immigrants first saw from the low decks and portholes of the steamships that brought them to this new land.

Nowadays more than 6 million visitors a year ferry from lower Manhattan or New Jersey to Liberty Island to see the statue, and about 2 million go on to Ellis Island.

In 1882, worried about the spread of dreaded diseases such as typhoid fever, the Federal Government took over the immigration process from the states. It set up stations in New Orleans, Louisiana, up the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico; at Angel Island in California’s San Francisco Bay; and in a creaky old fort called Castle Garden at Battery Park on the southern tip of New York’s Manhattan Island.

But Castle Garden’s administrators were unprepared for what was to come. Ships, packed with refugees from European wars and others seeking religious freedom, descended upon them.

So the Immigration Bureau commissioned a new processing center on a 1.6-hectare (four-acre) speck of land off Lower Manhattan once called Oyster Island and then Gibbet Island because a number of pirates were hanged there. A gibbet is a gallows.

For nine years in the late 18th Century, the sandy, scraggly island was owned by a colonial New Yorker, Samuel Ellis, a Welshman about whom not much is known. His heirs had little interest in the place when Ellis died in 1794, and they sold it to the young federal government, which admired its strategic location. The government built a fort there, and for the better part of a century, the public generally ignored the little lump in the harbor.

In 1892, to replace the older and overcrowded immigration gateway at Battery Park, engineers used subway rubble and ships’ ballast to connect Ellis to two adjacent islets, quadrupling the size of the island.

They built a sizable new processing station — only to see it and tons of immigration records dating to the 1850s burn a crisp one night five years later, in 1897.

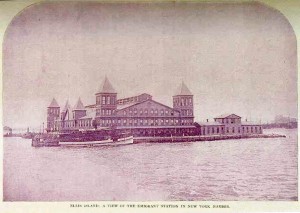

To replace it, they outdid themselves, constructing the 33 ornate, red-brick and white-limestone structures that are in place today.

Ellis Island’s magnificent new main building, with four soaring cupola towers, opened on December 17, 1900.

And this was its replacement, now a memorable immigration museum. (Carol M. Highsmith)

More than a century later, it and two other buildings that sat empty and decaying after immigration processing ceased, have been restored. But hospitals, quarantine buildings, and detention centers on the former unnamed islands Two and Three are decrepit today, their hallways heaped with fallen plaster.

Walking in and among them all, an almost tactile connection with the past is unavoidable. One can easily visualize steamships entering New York Harbor, and immigration inspectors sailing out for a perfunctory check of the paperwork of first- and second-class passengers. See, too, the barges carrying the liners’ steerage passengers to Ellis itself, where they received far closer scrutiny.

In this photo, taken about 1910, one of many visiting steamships sits off Ellis Island. (Library of Congress)

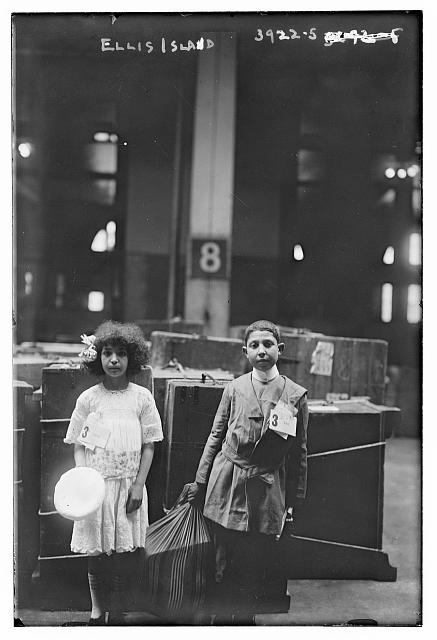

Each of these less-privileged immigrants wore an an identification tag from the steamship company, which had vetted the lower-class passengers almost as thoroughly as would government inspectors at the island. That’s because the ship lines bore the full cost of returning any immigrants deemed “undesirable” and marked for immediate deportation.

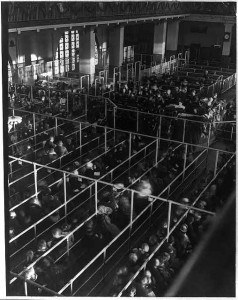

Five thousand arrivals a day — the record was 11,747 on April 7, 1907 — were sorted into lots of 250. At the processing building, they were required to leave their bags — a nerve-wracking proposition, for these were often the immigrants’ sole possessions — on the first floor, which became a chaotic baggage room.

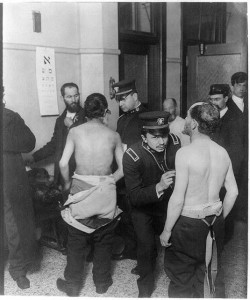

Then, anyone over 2 years old was required to walk unaided up a steep stairway to the mammoth Registry Room, which had all the comforts of a cattle pen. There, physicians looking for contagious diseases and emotional impairments administered a “30-second medical.”

A hasty but life-changing examination, in other words.

Thereafter, the immigrants were chalked with a code — including “S” for suspected senility, “SC” for scalp issues, and “X” for apparent mental disability.

Those who were not pulled from the queues for hospitalization, and likely expulsion from the country, were shunted into more lines, often for hours, before being questioned about their paperwork, criminal records, and work status.

It was an ordeal, as many of the immigrants were illiterate. Fortunately, many inspectors were fluent in several languages, and other interpreters were brought in to help as needed.

Despite the undercurrent of fear that pervaded Ellis Island, officials generally tried to humanize the registration experience.

Children were given warm milk, and those who arrived late and had to stay overnight were fed meals and housed in tight dormitory quarters — men in certain rooms, women and children in others.

There was even a rooftop play area.

But that hardly mitigated the terror. Immigrants well knew that families could be split apart based on the snap judgments of doctors and clerks. Youngsters with infectious diseases were segregated in a Children’s Ward. If the symptoms didn’t abate, they — and their mothers and siblings — were sent back to steerage quarters for a heartbreaking voyage home.

Such stories flashed back when Ellis’s processing center reopened in 1990 as the National Park Service’s immigrant museum.

At the time, Felice Kudman, a Park Service tour guide, showed Ken Reed, a VOA colleague of mine, around. “They would come up the steps directly into this room, the Great Hall” she told him.

As they were coming up the stairs, doctors were watching them to make sure they were not limping or breathing a little heavy. If they saw something that they thought was wrong with you, they would set you aside for medical examination.

If you got past the doctors, you would wait in this room to get to the legal inspectors. They would ask you questions that had already been asked of you in Europe. So if you answered any of the questions differently than you had in Europe or answered any of the questions wrong, you would be set aside for legal questioning.

When Carol photographed this iconic Main Hall window, the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers still stood in the distance. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Ultimately, the immigrants were funneled down “Stairs of Separation” that were divided into three sections. Those descending on the right proceeded to a New Jersey transit station; those on the left caught a ferry to Manhattan’s squalid tenement district. The center section was reserved for detainees bound for legal hearings, hospitalization, or immediate deportation.

Still, while Ellis Island has been called the “Isle of Tears,” about 97 percent of arriving immigrants were eventually approved for admission. Once they made it through the inspection gantlet, they could change their money into U.S. currency and buy a ticket to anywhere in America.

For Irish immigrants, that ticket was often marked “Boston.” For Italians — and for Jews from several European lands — “New York,” which loomed just across the water. Among the poor newcomers who entered the United States through Ellis Island and went on to fame, fortune or both were songwriter Irving Berlin, actress Claudette Colbert, aviation pioneer Igor Sikorsky, and Vaudeville singer Al Jolson.

Most immigrants, though, quickly learned that America’s streets were not “paved with gold.”

Galleries at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum are packed with haunting photographs as well as religious icons, household goods, humble valises, and recollections by the immigrants and guards.

Outside is a curving, stainless-steel Wall of Honor into which more than 500,000 names have been etched as a memorial gift from immigrants’ descendants.

Many of those names are altered from those that the immigrants carried to the embarkation dock. They were shortened — “Americanized” — for a variety of reasons. The legend that inspectors changed them to suit their own comprehension appears to be mythology. But some had been scribbled by steamship companies and never corrected, and others were simply misunderstood in the teeming inspection process.

Others were changed by the immigrants themselves or by their children so as to sound less “foreign” or “ethnic” and thus be acceptable to those who might be hiring them or renting them places to live. “Irving Berlin,” for instance, was born Israel Isidore Baline, and “Al Jolson” as Asa Yoelson.

The visitor experience can be profound. With Lady Liberty towering in the distance, Ellis Island stands as a monument to the figurative “golden door.” That’s a reference in Emma Lazarus’s poem “The New Colossus,” inscribed nearby at the Statue of Liberty. It mentions the opportunity for “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” to undertake a new life beyond that door.

One of Ellis’s decayed old buildings that sits in desperate need of salvation and renovation. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Those who did so included Felice Kudman’s grandmother, a Lithuanian, and an uncle, a German.

Standing where they stood, Kudman told Ken Reed, “You can feel the immigrants here. Sometimes you just stop and shiver a little. It makes you remember what it is like to be an American, and it is very nice to be reminded of it periodically.”

If you get there, you may be surprised to learn that you’re visiting Ellis Island, New Jersey.

In 1998, the U.S. Supreme Court settled a dispute in that state’s favor, in part because Ellis’s main island in the Hudson lies in New Jersey waters, closer to Jersey City than to Manhattan.

Since the Federal Government owns the island, this hasn’t helped New Jersey much. But it gives that state in New York’s shadow something to brag about.

One wonders what became of these children who passed through Ellis Island. (Library of Congress)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Molder. To rot or decay. The word is sometimes spelled with a “u,” as in the lyrics to the mournful song, “John Brown’s Body”: “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave.”

Polyglot. Multilingual. The term often describes a gathering of people who are jabbering away in many languages.

Vet. The verb form has little to do with the familiar nouns, referring to veterans or animal doctors (veterinarians). The verb describes the process of checking, verifying, or investigating the authenticity of something or someone. Many job candidates are carefully vetted before being hired.