I know, an ode is a lyric poem, something short and sometimes sung. I’m no poet, I don’t do “short” well, and you don’t want me to sing.

But this story is an encomium to majestic train terminals between which America’s passenger trains once traveled each day by the hundreds.

I should point out that there’s a very real distinction between “train people,” as I call them, and those who appreciate magnificent train terminals — as Carol and I found out the hard way many years ago. I’ll explain at the end of this story.

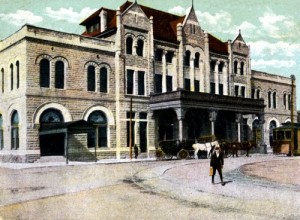

You don’t have to be New York or Chicago to have had an elegant train station, as this old postcard view of the Louisville & Nashville Raildroad terminal in Evansville, Indiana illustrates. (Library of Congress)

Nobody writes lonesome songs like the railroad ballads “Orange Blossom Special” and “The City of New Orleans” about train terminals. But there should be a Grand Central Station love song, or the like. A city’s, and even a small town’s, train station was usually a lasting landmark, a popular gathering place, and sometimes even an architectural jewel. Given our urge to tear old, decrepit things down, many of these rail terminals are, surprisingly, still around, all fixed up and looking as good as ever.

Washington’s terminal, for example. It’s one of many “union” stations across the land. The name refers, not to the American Union but to the consolidation, or uniting, of separate companies’ train operations across a city.

Railroads were king across America in 1903, when no less than President Theodore Roosevelt signed an act to provide for just such a station in the nation’s capital. A transportation palace, no less — a masterpiece of the “City Beautiful” urban-renewal movement that had swept the nation following the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago.

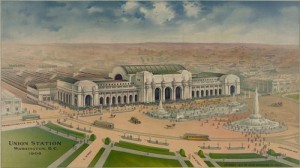

Washington Union Station, shown in another postcard view in 1906, as it was readying to open. (Library of Congress)

In fact, it was the impresario of that world’s fair, architect Daniel Burnham, who designed the neoclassical terminal a stone’s throw from the U.S. Capitol. The effect was properly pompous: Constantinian arches, delicate molding and sun-streaked gilt leafing, coffered ceilings, magnificent skylights, and towering statues by Louis Saint-Gaudens, inside and out.

Burnham’s train concourse, spacious enough to hold the Washington Monument laid flat, immediately became the world’s largest hall. Thirty-three platforms and 100 kilometers of track spread out behind it.

In the century that followed, remarkable stories unfolded there. Here’s just one:

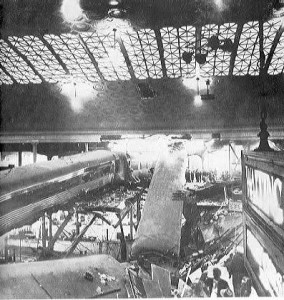

Thursday, January 15, 1953, had dawned cloudy and unseasonably mild as the Pennsylvania Railroad’s crack Federal Express gobbled its last taste of speed. Churning 18 minutes late on the overnight “owl run” from Boston, its GG-1 electric engine No. 4876 and 16 silver coaches pounded onto the switching tracks outside Union Station. Many of its 400 or so coach and sleeping-car passengers were coming to town to see General Dwight Eisenhower’s inauguration as president five days hence.

At the Ninth Street overpass, engineer Henry Brower coaxed the brake, but the train only hiccupped and did not slow down. He rammed the brake to “Full Emergency” for what should have been a squealing panic stop, but the Federal never responded. So Brower sounded the trainman’s desperate, staccato “Runaway!!” call on his whistle.

Four city blocks from the terminal, the train barreled into the 1° decline toward the station as a signalman in C Tower nearby grabbed the direct line to the stationmaster’s office and shouted the alarm.

Frantic warning cries were still clearing the concourse as the engine hit the track’s rigid end bumper head-on, reared like an enraged mustang, burst with a shower of sparks and dust through the station’s rear wall, and then crashed through the floor, carrying two lead coaches with it into the basement.

People later spoke of a miracle there, for dozens of baggage and mail workers would have been posted directly below the exploding crater created by the tumbling engine. Instead, they were on a coffee break. No one died, and only 43 people required hospitalization.

If you get to talking about Union Station with an old-time Washingtonian today, he or she will most likely mention that event, perhaps adding, correctly, that had that concourse floor not collapsed, the Federal Express almost certainly would have busted ahead into the waiting room, out the front door, and onto Massachusetts Avenue or beyond.

By that year, 1953, Americans had taken to the air and the highway and had begun deserting the nation’s passenger trains in droves. Over the next two decades, Union Station became a veritable mausoleum, grimy and soaked by water leaking from its ceiling.

What to do with the sad and sagging old structure?

Seers in Congress and elsewhere were looking ahead to the nation’s Bicentennial of 1976. They foresaw a gigantic pilgrimage to Washington, looking for a big birthday party. Where better to hold it than in a grandiose visitor center? And where better to create that locale than in the giant train terminal, all dolled up for the occasion?

“The Pit.” Visitors sat on the carpeted risers to the right and watched video presentations. (Carol M. Highsmith)

What materialized, though, was what Washingtonians cruelly dubbed “the Pit” — an enormous hole gouged in the station’s beautiful terrazzo floor. It led to a lounge in which tourists could watch a $1.5-million audio-visual show about the very things they could see for themselves if they looked out the front door. Around the Pit in the Main Hall, a cocoa-colored rug was soon pocked by cigarette-burns — $20,000’ worth of damage at one inaugural ball alone.

Anyone arriving and wishing to actually take one of the few trains that were still running was shunted to a walkway of wooden planks, leading to a narrow concrete path behind the station and ticket counters in a building the size of a gardener’s shed.

The short of the story is that the National Visitor Center was an embarrassing disgrace. The Pit closed in 1978, and with rainwater still dripping on what few strangers wandered in, the whole place shut down three years later. The public would not set foot inside Union Station for nearly eight more years.

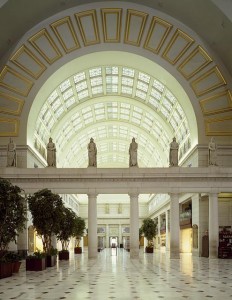

When they did, they beheld a renaissance in which the sodden, abandoned transportation shrine had been transformed into a gleaming multi-purpose showcase of theaters, cafes, and train portals. Rail passenger service had come alive in the interim, at least in the crowded Northeast, and so had Union Station.

The West Hall in the reopened Union Station, beneath some of Louis Saint-Gaudens’s Centurion statues. (Carol M. Highsmith)

At the grand reopening in 1988, Project Manager Don Cooper waxed philosophic. “Our hope is that, 80 years from now when people go to restore this building again,” he said, they’ll be able to come back to the work we did, go through our research and records and patterns that we used to re-create 1907, and have a solid base from which to again perpetuate the inspiration of Daniel Burnham.”

But it wasn’t 80 years before this happened. This very month, just 24 years after Burnham’s creation reopened, Amtrak, the nation’s passenger railroad — which counted 30.1 million departures and arrivals at Union Station in FY 2011 — announced that it and several partners would be remaking the terminal yet again as a “world-class transportation hub.”

The estimated $7-billion project will result in, among other things, new passenger concourses — including one for ultra-high-speed trains — and a high-rise building, called “Burnham Place,” above it all.

From all this, I hope you get the idea that, far from being torn up and torn down and carted off to landfills, great terminals that formed the nodes of the nation’s passenger-rail system are coming to life — albeit, often, with museums, shopping plazas, and performance venues as their star attractions.

I’ll introduce some of them using photographs, occasionally preferring to show you a historic image rather than a modern one.

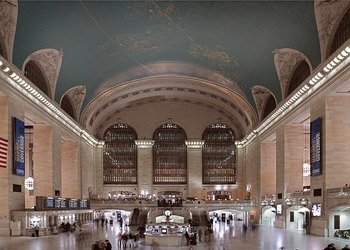

Refurbished Grand Central Terminal (Carol M. Highsmith)

One American train terminal, at the prestigious intersection of Park Avenue and 42nd Street in New York City, is so iconic that a cliché has grown out of it. When people bump into someone in a crowd, they sometimes remark, “Whattaya think this is, Grand Central Station?” The world’s largest train station as measured by number of boarding platforms (44), Grand Central is the city’s principal commuter terminal. Across town, Penn Station, beneath the Madison Square Garden sports arena, serves intercity passengers.

The first Grand Central was built at the behest of “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, owner of the sprawling New York Central Railroad, in 1871. Over half a century, until the forces of suburbanization sucked away its passenger lifeblood, it became the gateway to mighty Manhattan.

But Grand Central was destined for the wrecker’s ball, in favor of yet another office building, until the U.S. Supreme Court in 1993 upheld New York City’s landmarks law that saved it. Not only that, the terminal underwent a wholesale renovation to what its developers called “its 1903 splendor.”

The renovation must have worked: According to Travel + Leisure magazine, Grand Central is now the world’s sixth-leading tourist site, attracting more than 21 million visitors annually — presumably not including the train commuters.

Philadelphia’s Reading Terminal, named for one of the railroads that served it, in 1937. (Library of Congress)

I want to mention one more station that handles commuter rather than long-distance trains.

Ochs Bros.’ butcher counter at Reading Terminal Market. (Carol M. Highsmith)

It’s Reading Terminal in Philadelphia, into which regional trains from all directions once deposited passengers each day.

To Philadelphians and visitors such as Carol and me, the destination was even more famous as the location of the Reading Terminal Market, a giant indoor festival of delicacies, where one could gorge on Philly cheese steaks, fresh Jersey tomatoes, and soft “Pennsylvania Dutch” pretzels.

With ridership declining, the last train served Reading Terminal in 1984.

But a few years later, the building was transformed into a giant convention center, with a few remnants of its train décor remaining.

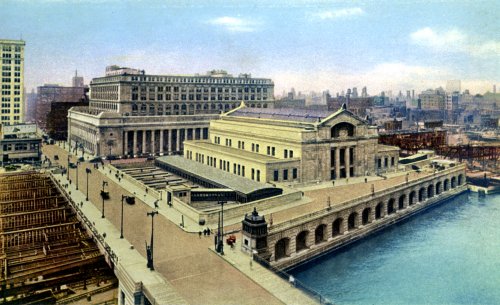

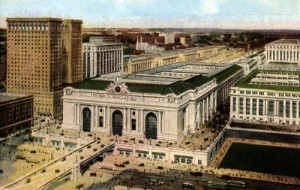

An early view of Chicago Union Station. (Library of Congress)

Chicago Union Station is a classic example of a “double-stub” terminal, meaning that trains approached the station from two directions, but most did not continue through, underneath the terminal.

Built for five different railroads in 1925, the station featured a Great Hall that covers a city block and includes two admired statues of human figures: one, holding a rooster, depicts day, and the other, grasping an owl, night.

This Union Station enjoyed a $32-million facelift in the early 1990s that included the removal of black paint that had covered the terminal’s skylights as a precaution against potential air raids during World War II; this seems extreme in hindsight, considering Chicago’s distance from Berlin (7,000 kilometers) and Tokyo (7,600 km).

Kansas City’s Union Terminal today. (Carol M. Highsmith)

When the Beaux Arts Kansas City Union Station, designed by City Beautiful proponent Jarvis Hunt, opened in 1914, it was the nation’s third-largest train terminal. It included 10 levels and 900 rooms — among them a Grand Hall illuminated by three chandeliers weighing 1,600 kilograms apiece.

K.C.’s station’s decline is a familiar story. In 1985, Amtrak transferred service on the few remaining passenger trains to a smaller downtown building. Various redevelopment plans for the grand terminal stalled or fell flat, but a regional sales-tax increase made a restoration, completed in 1999, possible. A reimagined science museum, called Science City, appeared in the terminal, along with a planetarium, railroad exhibits, and even an Irish museum.

Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Los Angeles’s Art Deco and Spanish Colonial “Union Passenger Terminal,” which debuted in 1939, epitomized the city’s brash grandeur. Passengers proceeded to their trains along polished, terra-cotta tiles past lavish indoor gardens. Often a backdrop in Hollywood films and television commercials, the station has been revitalized as a “multi-modal” transportation center, connecting passengers with regional buses and light-rail trains as well more than 35 long-distance Amtrak trains a day.

Cleveland’s Terminal Tower. (Library of Congress)

I saved Cleveland, Ohio’s “Terminal Tower” for last. As a child, I used to take the streetcar there. The world’s fourth-tallest building when it was dedicated in 1930, this 52-story skyscraper stood above subterranean marble ramps and catacombs leading to train tracks far below. More than 90 intercity trains per day pulled into and out of those tracks during Terminal Tower’s first few years.

But as cars and planes siphoned away business, the last passenger train left in 1977, and the couple of daily Amtrak passenger trains that pass through Cleveland now skirt downtown and stop at a small station on Lake Erie. Terminal Tower has been “repurposed” a number of times. It now holds a hotel and a new casino, which replaced the multi-story Higbee Department Store where my mother would drag me shopping when I was a child. We’d go down and peek at the trains sometimes, but there’s nothing but some light-rail commuter trains to peek at these days.

Trains v. Terminals

As I said many words ago, there are train buffs and there are admirers of train stations, and the two don’t always overlap. Here’s how I learned this:

More Saint-Gaudens statues, this time outside and representing elements such as Fire and More Saint-Gaudens statues, this time outside Washington Union Station. These represent elements such as Fire and Electricity. (Carol M. Highsmith)Electricity. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Years ago, Carol and I produced a book about Washington’s Union Station, and we were invited to sell some at the terminal’s grand reopening in 1988.

We sold 3,500 books that day as people lined up to tour the brightly reappointed station and walk through some nostalgic old steam locomotives and passenger cars.

And when somebody told us that train aficionados from around the nation would be in town a week or two later for a big gathering, we inquired, described our book, and were invited to hawk some there, too.

So we schlepped to the meeting, lugging a few hundred of our books and rubbing our hands in anticipation of another banner sales day.

We sold . . . 10 copies.

It seems that many “train buffs” don’t give a whit about stations. If we’d written the definitive book about classic locomotives, such as the old No. 58 Taunton-built 4-4-0,— we were told, we’d have sold every copy we had.

But we decided to leave such work, and oil cans and red bandanas and model railroads, to others.

One last lovely terminal view, this time inside Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Bandana. A large, brightly colored (often red) handkerchief, often carried by trainmen and other laborers.

Encomium. A speech or written words of tribute or admiration, much like a eulogy for someone departed.

Hawk. We all know to what the noun form refers. As a verb, to “hawk” means to loudly promote one’s wares.

Impresario. A person who organizes large events such as concerts and fairs.

2 responses to “Ode to America’s Transportation Temples”

[…] hard way many years ago. …. This Union Station enjoyed a $ 32-million … Read more on Voice of America (blog) Shocking At-Home Facelift Alternative Powerful Enough To Make Both Men and Women Look Younger In […]

The wonderful Union Station in Columbus, OH, was demolished and replaced with the ugliest convention center you’ve ever seen. For years out Amtrak Station was a trailer. We don’t even have a train station anymore.

During the Civil War, the infamous Confederate raider, John Hunt Morgan, escaped from the Ohio Penitentiary (also gone), walked down the street to Union Station and boarded a train to the south. I can’t remember how far he rode the train but his escape was successful. Sadly, all that remains of that gorgeous building is a single arch which was preserved in a tiny park nearby.