Many history majors have a hard time landing good jobs — or any jobs at all — out of college. Today’s big guns — business and entertainment — don’t pay much mind to what happened long ago.

But it’s a good thing a few historians did find jobs and are fact-checking our tales about the past, many of which have been muddled, botched, exaggerated, or simply made up to suit whatever story we’re telling.

I remember playing a party game called “Telephone” as a kid. It calls for several people. The first person tells the second a short story. I might, for instance, have mentioned the time I put a rubber band around my cocker spaniel’s stub of a tail and promptly forgot about it, leading to a painful infection for Taffy and a visit to the veterinarian.

The second person in line whispered the story to the third, and so on.

By the time each person had mis-remembered — and then mistold — one detail and then another, Taffy had become a cat, the rubber band was a mousetrap, and the poor, dying creature never made it to the vet.

Add to this problem of historical fuzziness the desire to put one’s own spin on a story — especially when there’s a buck to be made — and villains become heroes, events move far from where they happened, and characters who weren’t even there show up.

Thankfully, there are a few good historians around to prevent or correct it.

Ah, a golden-brown, stuffed and plump turkey: a delicious Thanksgiving tradition, but a relatively recent one.

And speaking of thanks, the classic case of historical reversioning is our country’s Thanksgiving celebration — the very favorite annual holiday of many of us, including me.

Next Thursday, we will gather around a lavish dinner for family and friends that begins with a prayer of thanks for our blessings. Some of us will cook a big meal for those at shelters and soup kitchens, or give money to send the warm trappings of Thanksgiving — emotionally and literally — to U.S. military personnel serving abroad.

This celebration is modeled after harvest-home feasts — especially what’s been called the “First Thanksgiving” in colonial Massachusetts. It’s the pleasant story of a cold, late-fall day almost 400 years ago, when about 50 pious English settlers called “Pilgrims,” who had barely survived their first year in the New World, shared a feast with their neighbors, the friendly Wampanoag Indians.

Here’s a lovely decoration, perhaps a placemat. And two of its components — corn and a pumpkin — may actually have been present at the “First Thanksgiving.”

Trouble is, according to curators at Plimoth Plantation — a living-history museum in the same settlement where the Pilgrims and Indians marked that harvest in 1621 — the Thanksgiving story is more fable than fact.

For one thing, the event likely took place in October, closer to the corn harvest.

For another, while the skimpy records from 1621 mention fowl, these were likely geese and ducks. They were certainly not the plump, domesticated turkeys that American families stuff and roast today. Apparently the Wampanoags went off and shot five deer as their contribution to the meal.

And you can forget the yarns about cheery First Thanksgiving illustrations of long tables piled high with breads and pumpkin pies. The Pilgrims had neither the sugar nor the wheat flour and ovens needed to make those baked goods.

There were cranberries around in Massachusetts — still are. Bogs full of them. But the Pilgrims sure didn’t serve cranberry sauce or the kind of wiggly cranberry gel you buy in cans. No sugar to make them with, remember?

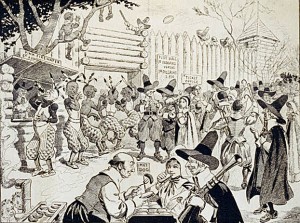

The First Thanksgiving isn’t just misrepresented. Sometimes it’s even ridiculed. This caricature shows Pilgrims eating hot dogs and Indians drinking “firewater.” Note the sign that reads, “foot ball ye Indians versus ye Pilgrims 2 p.m.” (Library of Congress.)

A food historian at Plimoth Plantation told me that Chief Massasoit and about 90 other Indian men — there’s no record of Wampanoag women coming along, so their participation may be a myth, too — conferred with the Pilgrims for a full three days. It wasn’t a single feast, but rather an ongoing conference at which food laid on tree stumps and crude tables was sort of available for munching.

Grazing, we call it today.

There were no plates, either — at least no fancy, ceramic ones — and probably no kitchen knives and forks and spoons. People cut meat with hunting knives and tugged at the carcasses with their hands, wiping them on anything that was handy.

And it’s unlikely anyone called the event “Thanksgiving.” A harvest, even a modest one, was something you’d expect to happen, not something amazing. As the food historian told me, “The defeat of the Spanish Armada back home in England — now THAT would have been an occasion for a Thanksgiving.”

There’s probably another myth lurking in the story of the Pilgrims. Although they did land in Plymouth, it probably wasn’t on this very “Plymouth Rock” of legend, preserved as a tourist attraction. In fact, it was likely clear across Cape Cod Bay, in what became Provincetown. (Library of Congress)

Nor, as our children are sometimes taught in school, were the Pilgrims up-tight religious fanatics who prayed all the time and went “tut, tut” to anyone who had a little fun. People confuse these Pilgrims with Puritans, a sterner, joyless lot that came to Massachusetts, also from England, a little later. They were the witch-burning crowd.

Pilgrims, by contrast, upheld the “merry” part of “merry, old England,” my Plimoth contact told me. Beer- and wine-drinking and feasting were part of their lives, assuming they could find something to shoot and eat.

And ignore the myth that this was the first of many happy Thanksgivings celebrated with native people who had willingly accepted colonization, and who joined the white Pilgrims in toasts to peace, prosperity, and happiness ever after.

The Wampanoags were rightly suspicious of the Pilgrims and their intentions. The white settlers soon enough broke treaties with the Indians, and their alliance lasted just 50 years before war broke out between them.

Discount, too, images you might have seen of men in Pilgrim costumes — fine coats, shiny shoes, and tall hats with big buckles above their wide brims. That was aristocratic garb. The struggling Pilgrims wore beaver hats and deerskin coats.

In 1932, Jean Leon Jerome created this highly romanticized, and terribly inaccurate, painting of the First Thanksgiving. (Library of Congress)

And despite the painting you see over to the right — I’m pretty sure this was the one on the bulletin board in school — Wampanoags did not wear feathered headdresses like those of Plains Indians — even though those of us who played Indians rather than Pilgrims in our school plays wore feathers galore. Wampanoag attire was spare and practical. And for sure, no one was running around New England in the nippy fall in skimpy loincloths.

Maybe the biggest Thanksgiving myth is that the First Thanksgiving was first at all. My friends the historians have pretty much proved that people near what is now El Paso, Texas, 3,300 kilometers [about 2,000 miles] away, staged a Thanksgiving celebration a full 22 years before the Pilgrims even arrived in North America. A Spanish explorer, Juan de Onate, threw the party on the banks of the Rio Grande River after leading a band of settlers across the Mexican desert to get there.

Of course, it would be 3½ centuries before Texas would even be part of the union, so it wasn’t an American Thanksgiving. But Plymouth was a piece of colonial Britain when the Pilgrims invited the Wampanoags over for duck and corn, so what’s the difference?

Not every Thanksgiving myth has percolated through centuries of time. It hasn’t been long at all since a modern one was circulated and widely believed.

Ever hear of the dreaded “tryptophan coma”?

A tryptophan coma, perhaps? More likely, the sheer volume of food and drink conked out this young man in Alice Barber Stephens’s 1896 watercolor, “Over-indulgence — a spoiled Thanksgiving.” (Library of Congress)

Tryptophan is an amino acid — one of the molecules that builds protein. For many years, it was thought that high levels of tryptophan in turkey acted like a sedative, triggering a snooze response in our brains after a big Thanksgiving dinner.

There’s no denying that I can hardly keep my eyes open as I let my belt out a notch following such a banquet. But tryptophan levels are no higher in turkey than in most other meats. And turkey is but a small part of the fare that includes potatoes, bread, stuffing, and sweet potato casserole. It’s those starchy foods, plus sugary delights such as pumpkin pie and whipped cream — and higher-than-normal helpings of beer, wine, and stronger spirits — that conk us out just as the after-dinner football game is about to kick off.

There’s one more Thanksgiving tradition that we could only wish were a myth: the higher readings on the bathroom scale the next morning.

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Percolate. To leach into something, or strain through tiny, porous holes, much as water picks up the color and flavor of ground coffee beans before percolating downward into a pot below.

Yarn. In its most familiar usage, yarn is a collection of interlocking fibers used in making clothing such as sweaters. But a yarn is also an elaborate story, often spoken, and frequently full of embellishments for dramatic effect.

8 responses to “Only in America: Thanksgiving Fact, Fiction”

Hello. We played the same game here except while it is called Telephone over where you are, here it is called Chinese whisper. I might have to dig in order to find out the Chinese thingy in this game. History is important because it tells us where we are from and it guides us to where we are going to. Then it teaches us a lot of things too. These days, we can share with each other our experiences through the internet. These experiences will one day because part of history, especially if the experiences are genuine.

like

Love the piece! I good-naturedly take exception to the idea that: “Many history majors have a hard time landing good jobs — or any jobs at all — out of college.” I have a BA in history – my wife has a PhD in History and we are surrounded by very succesful graduates of history programs. It is a field that yields its benefits gradually over time. So while it may be true that immediately out of college most of us floundered around or went straight to graduate school, the reality is that the skills of research, analysis and reporting, as well as the necessity of learning how to parse sources who often succumbed to ” the desire to put one’s own spin on a story — especially when there’s a buck to be made,” puts us in a very advantageous positions later in our careers. So out of college – over time – we do quite well. Strangely enough the previously-referenced historian’s skills have made me into a top-notch sales agent for residential real estate developments. It’s that no-nonsense mandate of “get the facts; don’t varnish them; present them so everyone can understand them; and then present an opinion of what they signify, oh – and do it on a deadline or you’ll fail the assignment.” It comes straight out of the study of history but puts me head and shoulders above most of my real estate competitors who rely on wishful thinking, fuzzy math and seamingly reliable data that is not reliable when you make the effort to look under the hood. So any young people reading this – pursue that history degree! We need you to and you will benefit!

OBVIOUSLY, anyone who passed the seventh grade would know that they didn’t eat a feast by our standards today. And yes, holidays’ meanings change with the times. Currently, Thanksgiving is a time to meet with family and be thankful. This article was stupid. If you can’t say anything nice (or entertaining) then keep your pen from the paper; I like Thanksgiving and I really, really don’t need you to write a whiney article about how inaccurate it is.

Quick reply to historian Sid Whelan’s comments: I LOVE historians. My middle daughter, Juliette, is a U. of Va. Ph.D. in history who DID find a job and now has a great one, as dean of Westminster College at the University of Richmond. And I concur completely that young people would get a lot out of a history major and degree. But I’ve heard too many horror stories about the lack of jobs for history grads, except in teaching, where there’s not much turnover. Go for that history degree, I say, but with your eyes wide open and a willingness to be flexible in job choice.

Ted Landphair

Not sure whether lela_lela is saying she LIKED the Thanksgiving posting, or was using the infuriating “like” as in, “like, you know, I, like, liked it.” Hope it’s the former. If the latter, I’ll have to fulminate on the “like” epidemic in another blog.

Ted Landphair

Well written article. Usually stumble upon quality articles right on this blog. Thanks much for sharing. I will add this website to my favorites list. One more thing, I was curious about paying for advert spaces on this blog. Looks like a sweet blog to advertise on. Great articles and nice design. Email me the advert info if you’re accepting new advertising. Talk to you soon!!!!

Fortunately from a presentation point of view, no advertising is accepted here. It’s one of the few “advertising-free zones” I know of, and what a blessed relief that is! — Ted Landphair