Those of us who write for the internationally targeted Voice of America have learned to keep a few things in mind:

|

| Not all homes in America look like this. In fact, not very many do |

One is that our reality is not the reality of many places to which we communicate. We need to be sensitive when writing about American fashion or food fads, for instance. We recognize there is severe poverty and hunger in many parts of the world, and that some among our audience will know of such privations first hand. It doesn’t mean that we hide America’s good fortune. But it should not surprise us if those who hear or read our words construe a story about mouth-watering steaks, or luxury cars in a celebrity’s garage, as flaunting our society’s excesses.

|

| This is Seattle’s skyline. That’s Mount Ranier off in the distance |

Nor can we take for granted that our audience is familiar with American places. If I write about Seattle, Washington, American readers – or most of them, I fervently hope – know at a minimum that it’s “out there somewhere” in the Pacific Northwest. I wouldn’t really even need the “Washington.”

But readers in Nepal may not know Seattle or Washington state, and it’s the height of national chauvinism to expect them to. Where in Syria is Aleppo? Just a hair under 100 percent of Americans wouldn’t have a clue or know there is an Aleppo. So why should we expect a Syrian to pinpoint Seattle?

Here’s a real example: In my last posting, I mentioned the great transcontinental railroad that metaphorically and physically united the country in the mid-19th Century. From the east, that line began in Omaha, Nebraska – railroads having already reached Omaha at the Missouri River. But someone overseas, reading that the new track was “transcontinental,” might logically assume that Omaha and Nebraska lie somewhere on the East Coast.

The third lesson, on which I want to spend some time, has to do with the English language. We in VOA’s Central Features Branch write all our original stories in English, as you’d surely expect, and they are translated into 40-some foreign languages for broadcast to different parts of the world, and broadcast worldwide in English by VOA’s English Service. Our readers, listeners, and viewers understand English to varying degrees. Many tell us that they love to read it and hear it, even though it’s a challenge to keep up. They concur that American English, in particular, has become the dominant international language of youth, science, music, movies, and the Internet.

|

| This looks like a book that could come in handy – for supposedly fluent English speakers as well as those learning the language |

But save for Avi Arditti and Rosanne Skirble’s “Wordmaster” series, to which I link in the archived Wild Words column to the right, most of us don’t spend a lot of time writing about the English language’s nuances. Most English idiosyncrasies don’t appear in Swahili or Uzbek or Amharic, nor do peculiarities of those languages apply to English.

However, one English-language matter has, as my mother would have said, “my liver in a quiver.” If the menace that I’m about to describe spreads to other languages, the world may be doomed!

|

| Lessons in this Saint Augustine, Texas, County school back in 1943 must have been so hard that it took two girls to figure them out! |

Part of the no-big-deal, ever-more-casual nature of American popular culture is a growing disregard for rules of language (not to mention dress and decorum) that used to be drilled into us in school and at home. These days the attitude is, “Rules, schmules. Rules are for fuddy-duddies. Like, chill, you know what I mean?”

No, I don’t know what you mean. Careless and incorrect usage such as, “Things are, like, going well between you and I” make me want to bite my tongue and gnash my teeth, and tear at what’s left of my hair.

|

| Now here’s a series of street signs that got the apostrophe right! Of course, they are in Gibralter, not the United State’s. (That one was just for fun.) |

Most annoying of all to this fuddy-duddy are the deliberate attempts to eliminate the humble apostrophe, on the pretext that this tiny but noble symbol of the possessive form is a waste of time and a bother. John Kelley reports in the Washington Post that two local governments in England have given up putting apostrophes in street names and signs. I can assure him that the apostrophe is long gone from thousands of U.S. places as well. St. Ann’s Court is “St. Anns Court.” Prince George’s County – next door to us in Washington, D.C. – is “Prince Georges” on a lot of maps and signs. Everywhere you look, you see “Freds Cleaners,” “Sals Barber Shop,” and “Riccardis Liquors.”

|

| Here’s an example of a shop sign whose designer who put in an apostrophe, all right, but where none was needed |

Every other American welcome mat reads “The Smiths” or “The Landphair’s.” OK, not the latter one. Americans have become so confused, intimidated, and annoyed by the little apostrophe that we just stick it where it sort of feels right: “The dress was her’s.” Or, as I’ve said, we consider it a nuisance and skip it entirely.

John Kelley’s own, renowned newspaper has all but scrapped the apostrophe on its sports pages. Post reporters write about “Capitals owner Ted Leonsis,” the “Redskins touchdown drive,” and the “Wizards foul trouble.” Thankfully, the news section isn’t discussing “New Mexicos senior senator.”

Yet.

|

| Oh no, where does it go? |

These assaults on the possessive form are not mere peccadilloes. They would be outrageous affronts in many other languages. Greek or Persian speakers who tried to turn “the cat’s ball” into “the cats ball,” for instance, would be thought daft – illiterate for sure. They couldn’t do it, because their possessive forms require whole new word endings. It is the ball of the cat, and it takes more than a zippy little apostrophe to make it so. Disregarding the special endings and rearranging of words that make a Greek or Persian word possessive would be akin to writing “the cat ball” in English. It would be nonsense, gibberish.

|

| Are this young texter and others like her responsible for the slow death of the apostrophe? |

John Kelley notes that text messaging is a villain in this piece, as it is in so many other recent assaults on our language. Who, thumbing away on tiny buttons, can be bothered to put an apostrophe in “John Browns body”? As they would write it, “Its not needed.”

Besides, many palm-held texting devices and cell phones don’t even have the apostrophe character. Here at the office, a texter after my own heart told me that she cannot bring herself to debase a good possessive by leaving out the apostrophe. She substitutes a comma.

Bravo, but little does she realize that the language laggards may already have lined up the comma as the next “unnecessary” punctuation mark.

If I gave in to all this linguistic sloppiness, you would be reading quite a different post. Something like:

Ive been following Freddy Featherbooms travel’s in Ecuadors and Perus’ jungle’s. I know the Featherboom’s well. They live right down the street from Carol and I, near Joes Bakery. Weve been to there house many time’s.

|

| When we send this contraption something, we’re “printing it out,” like sending out our laundry |

Two more language bursts:

Why, when we send a computer document to a printer, do we say that we’re “printing it out.” Aren’t we just printing it? If computers could print, would we be printing it in?

And speaking of punctuation, have you seen this brain-teaser? Lynne Truss included it in her #1 best-selling book (in Britain), Eats, Shoots & Leaves. Take the words below and, by using just two punctuation marks, change the meaning completely:

WOMAN WITHOUT HER MAN IS NOTHING.

(Answer at the end of today’s posting.)

With a chuckle in a recent meeting, my Voice of America colleague, the aforementioned Rosanne Skirble, noted that she gets a good deal of mail from overseas listeners, many of whom began tuning in to us on the radio long before VOA had much of a television or Internet footprint. But they had not seen the Voice of America name in written form very often.

So Rosanne reports receiving a good deal of mail addressed to:

“The Boys of America.”

|

| I don’t know if this was my cup or Dorothy’s. More likely, the latter |

The Boys of America story makes me think about Dorothy Jones, who was the office manager of a large Washington, D.C., radio news operation that I directed years ago, around Marconi’s time. She was one of those refined, stern women of some years who, we all knew, ran the place even though she lacked the title to do so.

One day a job seeker sent an inquiry directly to her rather than to me. This pleased her, and she was even prouder to read the address and salutation:

Ms. Dorothy Jones

WMAL News

4400 Jenifer Street NW

Washington, D.C. 20015

Dear Ms. News:

I did not grant the careless applicant an interview, but as you can imagine, Dorothy was “Ms. News” to one and all for the remainder of her distinguished career.

If only this had happened at VOA. She would have been Ms. News at the Boys of America.

|

| If you live in New Orleans, you might want to book a spot here before you die |

• The Times-Picayune, the daily paper in my old stomping grounds of New Orleans, recently published this note:

To post your death notice, please call The /Times/-/Picayune/ at 504-826-3551 or toll-free at 1-800-925-0000 or email funerals@/timespicayune/.com.

As another VOA colleague, Faith Lapidus, pointed out, “Wouldn’t it be a bit late by then?” Or putting it another way, if someone managed to post his own death notice, there’d be no need for an obituary. It would be front-page news.

|

| Good dogs like this are getting less exercise these days in the Detroit area |

• Speaking of death and timing, here’s an interesting follow-up to something I mentioned in an earlier post, that the two “daily” newspapers in the struggling automobile capital of Detroit, Michigan, are in such dire straits that, to save printing and delivery costs, they are now delivered in print form only three days a week, on Thursdays, Fridays, and Sundays.

Daily newspapers have been America’s traditional medium of notification when one of our neighbors dies. Families and funeral homes carefully prepare death notices and tributes. And if the person is at all famous, the paper often writes a news story as well.

But right now in Detroit, as Jeffrey Zaslow points out in the Wall Street Journal, “you won’t want to die on the wrong day. People may never get word that you’re gone.” If Detroiters have the nerve to die on a Sunday or Monday or Tuesday, and their funerals are set for Wednesday or Thursday, a whole lot of folks who might otherwise have made a point of attending simply won’t know about it because the next newspaper won’t arrive until Thursday morning.

|

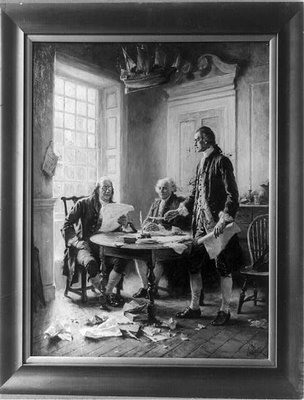

| That’s John Adams, middle, and Thomas Jefferson, standing, to whom Benjamin Franklin is reading a copy of the Declaration of Independence in this 1921 illustration by Jean Leon Ferris |

It’s enough to make the dying hold on for a day or two, as U.S. presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson are said to have done. They passed away on the same day – July 4, 1826 – not so much because they wanted to travel to heaven together, but because, it is said, that date would mark the 50th anniversary of the signing of the nation’s Declaration of Independence, which Jefferson had written.

July 4, 1826 was a Tuesday. Good thing neither Adams nor Jefferson lived in Detroit.

• And one last death note: Have you heard comedian Steven Wright’s line?: “I intend to live forever. So far, so good.”

On February 24th, a reader named Lindsay left a thoughtful comment about New Orleans on one of my archived postings. The 24th was “Fat Tuesday,” a rough translation from the French of “Mardi Gras” – the last Tuesday of Carnival revelry before the solemn Christian Lenten season in New Orleans; Mobile, Alabama; and smaller cities in French-speaking Acadian country of Louisiana and Texas.

|

| This is the sort of fun I missed at Mardi Gras this year. Sigh |

On the radio on that Tuesday, I heard Rex, the costumed King of Mardi Gras, make the ceremonial request of New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin that serious endeavors be suspended for the day in favor of masquing, parading, fancy balls, general merriment, and a drink or two or ten. (They don’t call the club that sponsors one of the big New Orleans Carnival parades “the Krewe of Bacchus” for nothing.)

Nagin assented with a flourish. I’m sure President Obama would also suspend serious work for our financially beleaguered nation for a time if he could.

Here was Lindsay’s comment:

|

| This is the photo of the Hibernia Tower to which Lindsay refers. It was taken from Bourbon Street in the heart of the French Quarter. Sigh, again |

“I happened across this blog because I was looking for a picture of the Hibernia Tower [a venerable bank landmark in New Orleans] bathed in Mardi Gras color,” Lindsay wrote, “and your blog contains a great photograph of it [by Carol]. It’s 3:45 Mardi Gras morning and I’m many miles from the Avenue where my heart longs to be – your photo let me go home for a little bit.”

I don’t know where you are, Lindsay, but I, too, pine for a whiff of sultry Louisiana air on a late winter’s morning. As I write this, I’m wearing a strand of cheap, gaudy, plastic Mardi Gras beads of the sort that Bacchus and other krewes toss by the thousands to the multitudes on Napoleon and St. Charles avenues and on Canal Street. The beads look truly dorky on me, but what can I say?

|

| Legendary 19th- and 20th-Century photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston, who has been Carol’s beau ideal, took this moody shot in the French Quarter in the late 1930s |

I’d make a Mardi Gras brandy milk punch for old times’ sake, but all we have in the office fridge is low-fat milk and no brandy.

Mardi Gras wouldn’t work in Washington anyway. There’d be 10,000 cops on the street on overtime, masks would be prohibited as a security risk, lobbyists would see to it that every parade float carried advertising, Republicans would boycott it if King Rex were a Democrat, and vice versa. Besides, the congressional commission studying the advantages and drawbacks of the event would not finish in time for the good times to roll.

|

| Here’s the National Museum of the American Indian in one of Carol’s photos taken before the “Indian/Not Indian” sign appeared |

The Voice of America’s offices sit directly across Independence Avenue from the four-year-old Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Hanging above its entrance is a flag that intrigued me. It turns out that another of my VOA colleagues, Susan Logue Koster, wrote about the three words on that flag, but I thought I’d share a bit about them here as well.

The flag reads: “Indian/Not Indian.” I assumed, incorrectly, that this had something to do with the terms “American Indian” and “Native American,” which to the country at large mean pretty much the same thing. But inside the community whose culture the museum displays, these terms have quite different connotations. My reading of the matter is that the former, “American Indian,” has greater currency these days, “Native American” being seen as an overly inclusive bureaucratic term invented by the Bureau of

|

| This is the kind of “noble savage” image of American Indians that Fritz Scholder detested |

Indian Affairs in the 1960s. Lakota activist Russell Means has written that he “abhors” the Native American designation. “We were enslaved as American Indians, we were colonized as American Indians, and we will gain our freedom as American Indians,” he wrote.

Here’s the genesis of the “Indian/Not Indian” message:

It is the title of two retrospective exhibits – one here and one at the museum’s gallery in New York – of the work of expressionist artist Fritz Scholder, who died in 2005. As Susan wrote, Scholder (rhymes with “shoulder”) “was the most influential figure in the history of American Indian art.”

“Indian/Not Indian” was the way Scholder – who was one quarter each French, German, English, and American Indian – described himself. At first he vowed to never paint Indian figures or scenes, since he objected to the idealized, stereotyped ways in which they are often depicted. But when he moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and experienced the reality of Indian life, he changed his mind. His vivid, brutally frank paintings of such images as a drunken Indian staggering down a street ignited controversies that simmer to this day.

Similar quandaries over one’s identity abound elsewhere in this multiracial country. One son of a white American mother and a black Kenyan father, President Barack Obama – who has lived in such culturally diverse places as Indonesia, Hawaii, and Chicago, Illinois – has described his own identity confusion at various points in his life. As he found out when others sought to label him during rough patches of his run for president, a flag marked “Black/Not Black” could easily have hung from his own front porch. Once he settled into identifying himself as a black man, others even began to ask if he were “black enough.”

Obama’s multiracial, multicultural life reminds us that we are a nation of many races and cultures, but Americans all. And as Russell Means would no doubt point out, American Indians were here first.

Finally, on what is turning into my “Mention Your Fellow Workers Day,” Faith Lapidus, of whom I spoke earlier, just told me a delightful story that I want to share.

When she identifies herself on the phone or leaves a message, she often begins, “This is Faith Lapidus at the Voice of America. Faith, like ‘faith, hope, and charity.’”

|

| Paul, later Saint Paul, was a Jew in Jerusalem who converted to Christianity and then worked to convert many others throughout the Middle East |

That makes perfect sense to those of us “of a certain age.” It traces to the Christian bible’s New Testament. Jesus’s disciple Paul is said to have preached, “Now abideth faith, hope, charity. These three, but the greatest of these is charity.”

Increasingly, Faith says, those on the other end of the phone react with a “huh?” as if she had spoken nonsense words, like, “Hi, I’m Faith Lapidus, as in Ogsfaith Prylob Znork.” More and more people have never heard “faith,” “hope,” and “charity” strung together. (Nor have they heard of Saint Paul.)

So Faith is testing other approaches. She tried “Faith, as in Faith Hill.” That draws blanks, too, from people who are not into country music.

She now reports somewhat greater success with this approach: “Faith, as in ‘You gotta have . . .’” – picking up lyrics from a 2006 George Michael song. (He being way cooler than the Apostle Paul.)

The next thing you know, Faith will be doing it like Michael does: “Hi, this is Faith Lapidus, ’cause I gotta have faith-a-faith-a-faith.”

That should take care of her first-name recognition. But no one that I know of – not George Michael, not Beyonce, not Coldplay, not even Frank Sinatra for us geezers – has put out a song with “Lapidus” in it.

WOMAN. WITHOUT HER, MAN IS NOTHING.

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Consternation. Frustration and confusion. It’s easy to be consternated by an overly wordy and tangled explanation of something.

Dork. This is not something you want to be called. A dork is a loser, an incompetent and even stupid person. Believe it or not, the word dates to the early 20th Century.

Fuddy-Duddy. A fuddy-duddy – usually referred to as an old fuddy-duddy, is an old-fashioned, stuffy, stuck-in-the-past dullard. Nobody can quite lock onto the term’s origin, but we know that a “dud” is a dull disappointment. A fuddy-duddy’s a bit like an old fogey, and neither is a compliment.

Peccadillo. A small sin or indiscretion, not worth getting too worked up about.