On our latest trip, Carol and I headed west from Washington, D.C., through states such as West Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana en route to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Then we turned south toward our ultimate destination: New Orleans, Louisiana, about which I wrote last time.

No sooner did we begin to discuss the return trip to Washington than Carol started lamenting, rather plaintively if I do say so, that we hadn’t had the time to stop in Columbus on our way down. Could we somehow get there going home?

Do you think little Columbus, Indiana, would have towering buildings? This is the Ohio Columbus, and that little rotunda-looking thing is the Ohio capitol. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Columbus — Ohio’s capital? I asked her. We’d been there a dozen times.

No, she said. Columbus, Indiana.

I have traveled to every U.S. state, every big city, most middling ones, and hundreds of small towns, and I’ve read about nearly every other American place worth knowing. But I had to confess: I didn’t know there was a Columbus, Indiana.

“It’s a dream place,” Carol assured me. Or so she’d heard. A dream place if you’re an architectural photographer, which she had been before she expanded her palette to include just about anything remarkable across the country.

A fact check followed: Columbus, population 44,000. That makes it the 20th-largest city in Indiana, which isn’t saying much. It’s a farming and industrial town on the White River, where they used to make cars and where giant Cummins, Inc., still produces big diesel engines.

“Doesn’t sound dreamy to me,” I scoffed.

It’s “the Athens of the Prairie!” Carol insisted.

So we detoured from our usual route and stopped there on our way home. And stunningly, our experience matched that of a Saturday Evening Post writer who had passed through in 1964. In fact he called his story “Athens of the Prairie.” I later learned that the compliment had first been bestowed upon little Columbus right about then, by no less than Lady Bird Johnson, the nation’s new first lady and a one-woman force for city beautification.

This is pretty much how the Saturday Evening Post reporter would have seen the Bartholomew County Courthouse and tower 47 years ago. (Columbus, Indiana, Convention and Visitors Bureau)

Here’s how the Saturday Evening Post story began: As a motorist rolls toward Columbus, Indiana, he will see little that distinguishes it from other Midwestern towns. From across the lonely cornland, the belfry of the county courthouse possesses an antique prairie charm. The countryside yields to the usual commercial blight — a nondescript shopping center, a roadhouse circled by skittering neon lights that spell out “Bob-o-link,” and a snack stand shaped like a root-beer mug.

Then, predictably, there are the old homes and the humdrum ranch-style houses.

But suddenly, the unexpected: one building, then another that seems to have been plucked from a city of the future. The townspeople view all this architectural splendor with a mixture of pride, bewilderment, annoyance, and bemusement.

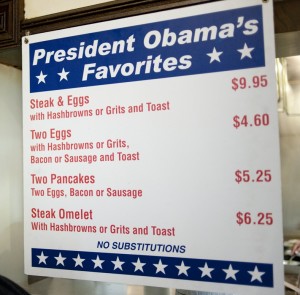

Eero Saarinen's 1954 bank building in Columbus. (Columbus, Indiana, Convention and Visitors Bureau)

The roof of a modernistic bank by Eero Saarinen is topped with inverted cups that look like halved tennis balls. Hoosiers have labeled it “The Brassiere Factory.”

As a whole, Columbus will never be a delight to the eye. But one way people learn the difference between the mediocre and the imaginative is to live with both. Today the citizens of Columbus are in a better position than most Americans to make that distinction.

That story went on to describe a veritable miracle of modern architecture in those “cornlands”: It has since grown to include 70 distinctive buildings and public-art pieces by legendary architects, including Saarinen, the Finnish-American best known for his dramatic designs of the soaring, stainless-steel Gateway Arch in St. Louis and the futurist passenger terminal at Dulles International Airport outside Washington.

I.M. Pei, Cesar Pelli, Harry Weese, Robert Venturi, landscape architect Dan Kiley, sculptor Henry Moore, and Eero Saarinen’s father Eliel, too. If you know a lot about modern architecture and art — I don’t profess to — you know the magnificent scope of these men’s work. I actually met Harry Weese when he and his associates completed a grand restoration of what had been the forlorn Union Station train terminal here in Washington.

OK, so maybe Columbus is Athens-of-the-Prairie-like. But that begs an obvious question:

How in the world did a little town of 12,000 — its population in 1942 when Eliel Saarinen led the grand parade of architects — become such a modernist showplace? Why there, in the tall corn, of all places? And why then, when most Midwest towns considered even television and nylon stockings to be suspiciously newfangled?

In that year, 1942, the First Christian Church in Columbus needed a new sanctuary. It could have built a traditional Gothic one, with a high steeple and abundant stained glass. But the congregation — especially one of its most prominent parishioners, J. Irwin Miller, the general manager of Cummins Engine and a modern-architecture buff — had other ideas. The church went radical by corntown standards, reaching out to the Finn Eliel Saarinen, designer of Helsinki’s Marble Palace, who had moved to the United States and was teaching at the University of Michigan.

The dramatically different First Christian Church. Go to the end of this posting for a gallery of large images of other Columbus delights that Carol photographed. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Saarinen turned them down flat. But Miller went to plead with him, noting that he and his Columbus friends genuinely sought a structure that would reflect “a rich inner life but a simple outer life.” Saarinen relented and came up with a building that looks, to my eyes, more like a fire station with a bell tower than a church.

But I already told you how little I know about modern design. The congregation loved it, and their neighbors learned to tolerate it.

Perhaps that softened local sensibilities for what was to come. The modernist dike broke a decade later, in the 1950s, beginning with Miller’s own residence of what one source calls “flat and flowing” design by Saarinen’s son, Eero.

Then came Irwin Union Bank and Trust, also by the younger Saarinen, whose heavy-on-the-glass design shockingly exposed the bank’s work areas for all the world to see. It was almost greenhouse-like, in an era when banks preferred the mysterious fortress look. Read the rest of this entry »