By Barbara Slavin

President Barack Obama’s announcement Monday that the United States is lifting practically all restrictions on the provision of weapons to Vietnam caps a remarkable turnabout in relations between the two former adversaries.

Four decades after U.S. forces retreated in defeat from a bloody and ill-considered war, the United States is now the largest market for Vietnamese exports. Nearly 19,000 Vietnamese are studying in the U.S. and 80,000 visited last year, insuring that links of trade, culture and investment will continue.

Two members of Vietnam’s ruling Politburo were graduate students at U.S. universities, recipients of Fulbright scholarships. On his trip, Obama announced the opening of an American university named for the late senator J. William Fulbright — who created the program of scholarships for foreign students — in Ho Chi Minh City, the former Saigon, capital of what once was South Vietnam.

Vietnam has become an increasingly popular tourist destination for Americans, particularly war veterans eager to see what has become of the place where 58,000 of their compatriots – and more than a million Vietnamese – died in a failed effort to prop up an anti-Communist government in the southern part of the country. Last year, more than half a million Americans traveled to Vietnam.

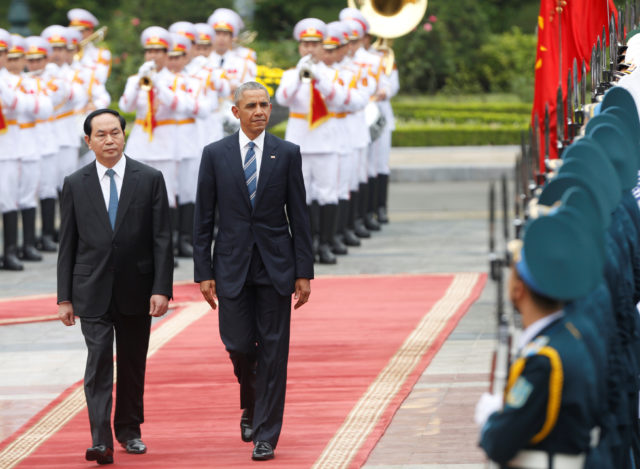

U.S. President Barack Obama (R) and his Vietnamese counterpart Tran Dai Quang review the guard of honour during welcoming ceremony at the Presidential Palace in Hanoi, Vietnam May 23, 2016. (Reuters)

U.S. veterans of the war, including Sen. John McCain of Arizona, who was imprisoned in the infamous Hanoi Hilton after his plane was shot down over North Vietnam, led the way toward reconciliation by convincing Vietnamese authorities to cooperate in the search for remains of Americans still missing in the conflict. Another veteran active in the effort to restore ties, former Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry, is now U.S. Secretary of State and accompanied Obama on his trip. A third veteran, former Nebraska Sen. Bob Kerrey, who lost a leg in the conflict, is chairman of the board of the new Fulbright University.

Obama has thus built on the work of predecessors. The trade embargo was lifted in 1994 and Bill Clinton normalized diplomatic relations with Vietnam in 1995.

Obama has added to the list of former foes, restoring full diplomatic ties with Burma/Myanmar in 2012 and with Cuba last year. In March, he became the first U.S. president to visit Cuba since Calvin Coolidge. American tourists are following in droves to experience the Caribbean nation only 90 miles off U.S. shores.

Obama has also scored a breakthrough with Iran, negotiating a landmark nuclear deal that required unprecedented bilateral contact at senior levels and that created a channel for continued contacts after Obama leaves office.

Full diplomatic relations are not yet realistic given continued hostility in both the U.S. Congress and on the part of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and a powerful faction within the clerical-military establishment. But if the nuclear deal holds, there is at least the prospect of a gradual improvement in ties as Iran slowly reintegrates into the global economy and the generation that orchestrated the 1979 Islamic revolution passes from the scene.

While Iran and the United States differ over many aspects of Middle East policy, particularly regarding Israel and Syria, they share opposition to Sunni Islamic terrorism, much as the Vietnamese seek an American hedge against a rising China. Iran is also eager for foreign investment and may find that without more cordial ties with the United States, it cannot reap the full benefits of the nuclear agreement and satisfy the aspirations of a young, outward-looking population.

When Obama first ran for president in 2008 on a platform of reaching out to hostile nations such as Iran, he was pilloried by some politicians – including Hillary Clinton – for his alleged political naiveté.

Now even Donald Trump appears to have caught the engagement bug, promising, if elected president, to travel the world negotiating deals with the likes of Russian leader Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

Such personal summitry is risky unless it is well prepared by officials lower down the diplomatic food chain. But the impulse to build bridges with adversaries is laudable at a time when the broadest possible coalitions are required to resolve conflicts and deal with transnational crises such as terrorism, climate change and pandemic disease.

Obama, who was warmly received by large crowds in Vietnam, noted that he was only 13 when the Vietnam War ended and that most Vietnamese do not remember the conflict because they were not born until it was long over. With a median age of 29, Vietnam is now a rising economic star in Asia, albeit one still marred by restrictions of freedom of speech and political activity, as Obama noted several times during his trip.

Addressing a huge audience at a convention center in Hanoi on Tuesday, Obama focused on the positive. He said that the example of U.S.-Vietnamese rapprochement “holds lessons for the world. At a time when many conflicts seem intractable, seem as if they will never end, we have shown that hearts can change and that a different future is possible when we refuse to be prisoners of the past,” Obama said. “We’ve shown how peace can be better than war.”