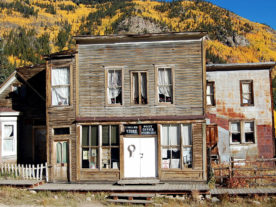

In 2000, teen labor force participation rate was 56 percent, compared to 39 percent in 2014. (Photo by Flickr user Lee Davenport via Creative Commons license)

Over the past 15 years, the number of American teenagers working part-time jobs has decreased dramatically, which is bad news for the U.S. labor market.

In 2014, only 1 in 5 teens in school (22 percent) had a job, down 16 percentage points from 2000, when more than 1 in 3 teens in school (38 percent) worked.

“It’s not worrying for the same reason that you would worry about older people because usually teens don’t need to work to support themselves,” said Martha Ross of the Brookings Institution, who co-authored a paper on the subject. “So the concern is more about how this is going to affect them down the road in the labor market and their ability to make a transition from school to work?”

In 2000, the participation rate of the teen labor force — workers between the ages of 16 and 19 — was 56 percent, compared to just 39 percent in 2014.

In 2000, the participation rate of the teen labor force — workers between the ages of 16 and 19 — was 56 percent, compared to just 39 percent in 2014.

Research shows reduced work experience for high school students, especially those who don’t go on to college immediately after graduation, is associated with lower employment rates and earnings in later years.

In 2014, the 10 largest employment sectors for workers between the ages of 16 and 19 were: eating and drinking establishments, grocery stores, entertainment and recreation services, construction, apparel and accessory stores (excluding shoes), colleges and universities, department stores, child day care services, landscape and horticultural services, and elementary and secondary schools.

Teens can learn a great deal from their first job, where the environment is very different from school where adults are there to focus on helping students learn. Not only are the stakes lower if they make a mistake, but teen workers learn key skills — responsibility, assessing situations, asking for help and receiving feedback — that can only be learned through direct experience.

“The structure of the workplace is very, very different,” Ross said. “For one thing, you have other adults that you can learn from in a different way than you can learn from teachers. And the workplace is not all about you, as a teenager, it is not about your learning. You are generally part of a team and you have to accomplish goals and complete tasks that benefit the business, or the nonprofit or the organization, in some way and that is a different mind set.”

Research shows a positive association between the number of hours a teen worked in the previous year and whether they were currently employed, which demonstrates that previous employment is associated with subsequent employment in teens. (Reuters)

Ross says it’s harder for young people to make the transition from college to a full-time job if they’ve never worked before.

Experts are conflicted about what’s causing the drop in teen employment. Many young people work less as the demands of school — higher level courses as well as extra-curricular sports and club activities — increase.

And, in a faltering economy, teens have the least experience and weakest networks when it comes to finding a job.

However, there is also a decreased labor force participation across all age groups, which suggests there is something going on in the labor force that’s changing the demand for workers.

And that change in demand appears to be hitting youngest workers the hardest.