FILE – The annual Steuben Parade, in New York celebrates German-American culture and is billed as a symbol of friendship between the two countries. (AP Photo)

People with German ancestry have long dominated the U.S. melting pot yet their stamp on American culture — once so proud and robust — seems to have all but disappeared.

MORE ABOUT AMERICA

People of German Ancestry Dominate the US Melting Pot

This US Ethnic Group Makes the Most Money

Why So Many US Koreans Are Dry Cleaners While Arabs Are Grocers

There are more than 49 million Americans — 16 percent of the population — with German ancestry, according to Ancestry and Ethnicity in America, which used data from the 2010 Census and the 2006-2010 American Community Survey.

At the turn of the century, just before the United States entered World War I, German Americans accounted for about 10 percent of the population and their presence was keenly felt.

“They were very proud and they clung to their culture very strongly. They still spoke German everywhere…They were almost arrogantly proud of what they thought was a superior German culture and a lot of them didn’t want to integrate and assimilate in the United States,” said Erik Kirschbaum, author of Burning Beethoven: The Eradication of German Culture in the United States during World War I. “They wanted to preserve their culture and keep it intact as long as they could.”

German immigrants flocked to New York and Chicago, and residents in numerous small Midwestern towns spoke German almost exclusively. German-language newspapers, theaters and churches flourished.

In some of these areas, the German influence was so pervasive that other non-German settlers ended up learning German so they could communicate with fellow residents. Germans helped establish General Electric and designed New York’s Brooklyn Bridge. They dominated the beer industry and that influence lingers in name brands like Busch, Miller and Pabst.

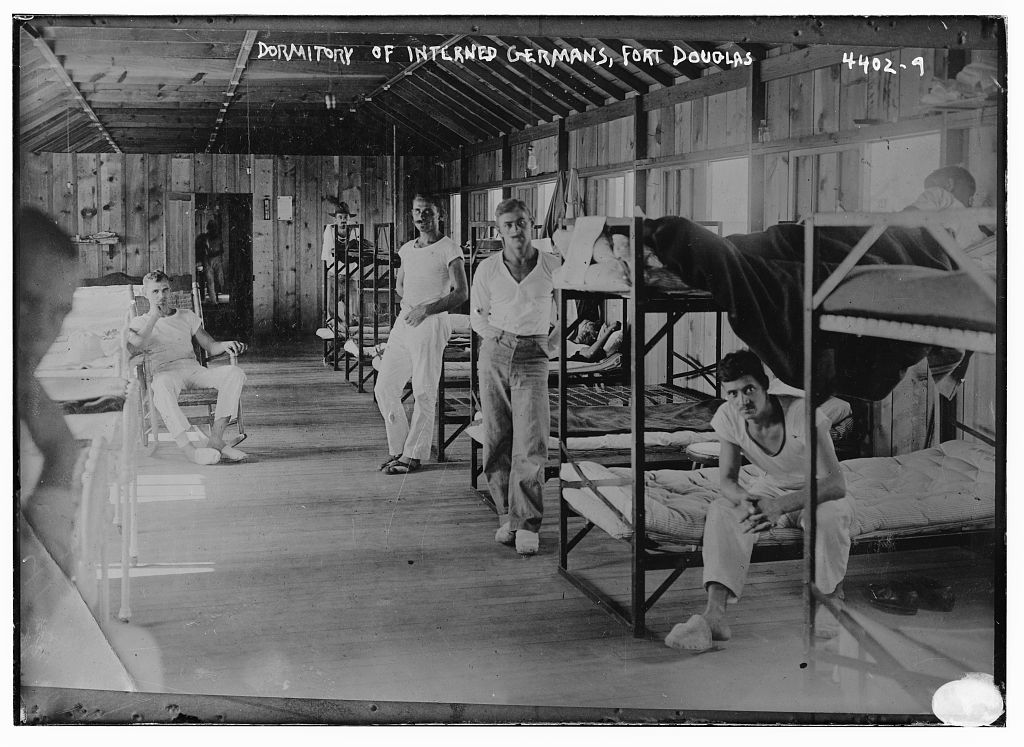

Dormitory for interned Germans at Fort Douglas, Utah. (Library of Congress)

The situation took a dark turn for German Americans when the United States entered World War I. Suddenly, as anti-German hysteria swept the country, America’s largest, most powerful minority was considered suspect.

“A lot of people thought the country was filled with spies and saboteurs and actually 30 Germans were killed by mobs and lynch mobs,” said Kirschbaum, whose own grandfather grew up speaking German but refused to speak in the language in his later years.

Shortly after declaring war on Germany, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson required about 250,000 German-born men — aged fourteen and older — to register their address and employment at their local post office. Within a year, that order was expanded to include women. About 6,000 of these people were arrested and 2,000 of them, who were deemed “dangerous”, were sent to internment camps.

German language books were taken out of schools and libraries and burned by so-called patriotic organizations that wanted to make sure German was eradicated from the American landscape. Kirschbaum says German Americans, who saw Germany as their mother and America as their wife, felt they had to make a choice.

“They suddenly realized they can’t be both German and American,” he said. “And after the war, a lot of them felt they had to assimilate, there was no choice and a lot of them did. A lot of them became thoroughly American. They stopped speaking German. They stopped teaching their children German. They stopped reading German newspapers and they became whole-hearted Americans.”

And in doing so, much of the German culture they’d proudly held onto for so long, slowly vanished from the American landscape.

Today, Kirschbaum sees disturbing parallels between the anti-German sentiment that swept the nation a century ago and the rise of anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment in the U.S. since the September 11, 2001 attacks.

“There’s definitely a parallel between the United States government turning sauerkraut into liberty cabbage during World War I and some people in Congress trying to change the term French fries into freedom fries after 9/11,” he said. “It’s another sad chapter in American history that perhaps could have been prevented or avoided if more Americans knew about the history and the way they persecuted German Americans 100 years ago.”

(Teaser photo by Flickr user momentcaptured1 via Creative Commons license)

This US Ethnic Group Makes the Most Money

This US Ethnic Group Makes the Most Money Why So Many US Koreans Are Dry Cleaners While Arabs Are Grocers

Why So Many US Koreans Are Dry Cleaners While Arabs Are Grocers

Shameful comparison by Kirschbaum: “Freedom Fries” was not “anti-Arab” or “Anti-Muslim” sentiment, but anti-French. It was an attack against France when France did the right thing: it rejected the illegal immoral 2003 bombing and invasion of Iraq which as we now know were based on lies. Instead of thanking France, they attacked France.

Second, the phrase “freedom fries” became widely know when the Republican Chairman of the Committee on House Administration, Bob Ney, renamed the menu item in three Congressional cafeterias in response to France’s opposition to the proposed invasion of Iraq. So its prominence was started by a politician for political reasons (pro-invasion) and was a change in the cafeterias in Congress – politicians acting. In WWI on the other hand it was not spearheaded by politicians but just small businesses afraid that the U.S. public would not buy anything from them if they sold it with a German name, hence “freedom cabbage”

But even if we put aside the distinction of who spearheaded the re-naming, the basic parallel is wrong: In WWI it was a re-name that, agree with it or disagree, this is just a fact — was re-naming it away from the country a U.S. was at war with, Germany. Completely different in 2003: the U.S. was not at war with France, the country that was targeted by the rename away from “French Fries”. It’s absurd to suggest the two are somehow very similar.

I have German blood – Jewish German blood, in my ancestry, and I have no problem defending German rights, or criticizing, like Dr. Gregory Stanton, lawyer and president of Genocide Watch, things like the WWII firebombing of Dresden, for example. But liberty cabbage? Please. We owe France (and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians) an apology and more for 2003 but “liberty cabbage” was the same? I don’t think so.

ED. That was a concise and brilliantly written critique. Thank You.

I have to agree with you. Thank you ED.

Liberal idiots permanently blame America for Iraq invasion when less than 50 000 Iraqies died.Today liberal Obama instigated ME disaster that currently costs more than 200 000 , and the end is not seen.

Dear PermBleeder,

1. You’re starting off in the wrong direction with “Liberal idiots permanently blame America for Iraq invasion” because it is America’s fault that America invaded Iraq.

2. Where do you get the 50,000 Iraqi deaths figure? Most studies have concluded 174,000 dead between 2003 and 2013.

3. I don’t speak conservative-douche, so you’ll have to explain ME (you might want to take a course on how to write clearly).

PermReader you may remember that one of the key reasons for Obama’s 2008 election was because he promised to withdraw from Iraq. Good or bad, he was fulfilling the U.S. electorate’s desire for withdrawal. So you should probably aim your shotgun at the American people in general.

Evidently, you have forgotten that during the Irag war, the US found out about a backdoor deal France and Germany had with Saddam to buy oil outside of EU.

But now can the Americans persecute the Muslims?

It is understandable that immigrants may suddenly find themselves in a situation in which they have to decide between their new homeland and their old one. That is their choice, and it is necessary that everyone be aware of this and take the proper precautions. No immigrant should be offended that people are aware that this decision can be difficult, but it is a decision that necessarily has to be made at times when loyalty to both countries becomes impossible.

America tried to persecute its own citizens only because they had German roots! the people of German origin turned narrow minded Cowboys and Yankees into civilized industrialists and they got prosecuted for it. that is criminal act of treason against humanity and the US will pay for it by losing its superpower status in the world today. Treacherous Anglo would like to think that the German nation is lost forever after mass killings of Dresden in which they tried to annihilate cultural aspects of mankind in this planet and now the German nation is more powerful than ever. May the god strike enemies of human civilization.

Solaris,

Yes. America will lose its superpower status.But not because of what we did to Germans. That stain doesn’t compare to what we did to Native Americans, Africans (and African-Americans), Chinese, Japanese, Irish, etc. America has mistreated those considered lesser for far too long.

If you look at our standing in the 21st century. From Terrorism committed on U.S. Soil (Homegrown and groups we trained) to the 2009 financial breakdown of our own doing to the fact that our congress has been the biggest impediment to restoring America’s stability… We’re our worst enemies.

Growth, blossoming, and death is not only the cycle of life. It is also the cycle of politics and nations. America’s power has crested. We could maintain our status in the world for a short while longer, but America is blinded by its own lies; We believe we are not racist, we refuse to heal our sick (horrible healthcare), we give tax breaks only to the rich –thereby depriving our working class the ability to survive–, we refuse to give our children an education (School systems are being shutdown even as I write this), and rather than doing what’s right, zealots in office refuse to do their jobs because they want to make a political point.

That’s no way to maintain superpower status. Many countries have already surpassed us in most respects.

Thank you for sharing your brilliant opinion, if the US listened to real patriotic ones like you it could go hand in hand with Nike until the end of the world.

Thanks Captain Sarcasm.

The truth is alweays the specific one.Great German culture posessed the features that brought Germany to nazism, but had the great potential of self-purification.This helped the German-origin Americans to give back their proud of German culture,I think.But the common “anti-imperialistic” howl of leftist support of Muslim immigrants is the pure deceit. Capitalism-hate of the left turnes them against their culture to the Muslim medieval darkness and anti-humanism. Defend Europe realy progressive,non leftist culture.

I know well that the craven liberal censure will ban my comments as the “liberals” always do with the heterodox oppinions.

Of course, “Freedom fries” was ridiculous. But to my knowledge, neither McDonald’s or the tens of thousands of restaurants that serve French fries ever changed the name.

If the subject of this discussion is about the real role of german origin people in US, I think they didn`t vanished from the none of real life, including culture. But their real role you could see if you regard the structure of the US Congress by names of senators and congressmen, and even more if you see the names of owners of the bigest US companies.

I did not like this piece, and I question VOA’s motive behind it. German culture has not “vanished” in the United States, as the headline and narrative suggest. There are German-American associations in most all major cities in the East, and where Germans settled. Likewise, German restaurants. Likewise, Lutheran churches. German language and culture is still taught in universities; although Arabic and Chinese languages overtook The German as a fad, and as a means for enhancing chances of future employment. Kirschbaum and the author of this VOA article, Mekouar, missed much of this. As for the general theme of this piece, the reason German culture in the USA is less apparent today is staring us all in the face – – there are decidedly less immigrants coming to the United States from Germany. Secondly, the German culture is more akin to assimilation where traditional European and Western values are held dear, in contrast to other peoples arriving in the USA today whose cultures have no chance, or desire, to assimilate, and whose community leaders are attempting to use all measures, legal and otherwise, to maintain segregation and ensure they do not.

I think it`s very important for the american people. i.e. american nation, to be really multicultural nation, based on the diversified traditional and cultural routes from all over the world.

There used to be an area on the Upper Eastside on 86th Street which was the denominator when I was growing up for Germantown. Some of it went along 3rd and 2nd Avenues as well. It was populated with German restaurants and butcher shops and other food stores, as well as apothecaries along 86th from west to east from Park to First Avenue and that was in the late 1960s and still well into the start of the 1980s when it quickly dissipated to other parts of New York and the metropolitan area. It ought to be remembered as well that much of Long Island is of German ancestry, which is why there is still nude bathing at Robert Moses State Park, as a cultural holdover of Germanic tradition.

Sorry, but more Americans are of British of German ancestry. True, among whites, “German” is the largest self-reported ancestry (15% in 2000), followed by “Irish” (11%) but this is deceptive. Recent U.S. censuses include, in addition to English, Welsh, Scottish, Scotch-Irish, and Cornish, the option to identify as “American.” Those who self-identify as “American” (7% in 2000) tend to be whites from Appalachia and the South, and their ancestry tends to be overwhelmingly, even exclusively, British (mostly English, but also Scotch-Irish). Taken as a whole, then, Americans of primarily British stock constitute more than 20% of the population. Moreover, many Americans who self-identify as “Irish” are, in fact, of Protestant Scotch-Irish (Ulster Scots) descent.

It is not about which ancestry is the largest, it is about criminal action against humanity and I am sorry for you, meanwhile if you are from English ancestry, I do hope the other Brits are not like you especially in justifying inhumanity through ancestry percentage.Killing one innocent is as criminal as mass killings of many, no matter how many the motive is the same. Arabs and Muslim may find your comment interesting since they do love British Empire and terrorism.

British is not ethnicity, German is

And this is exactly how it should be. The melting pot is not about bringing your culture to America and preserving it. Its about becoming American. My father came over from Italy, and while he still loved many Italian things, he considered himself American. We spoke English at home and I never even learned Italian. I was no different than the kids of Irish descent in my neighborhood. THAT is the melting pot; not coming to America and keeping your own culture. Otherwise, why are you here? Its not just a piece of land for people to come and set up their Mexican or Irish or Japanese settlement on. Its a country, a culture. America absolutely has culture and a way of life. Love it or leave it.

Main stream euro-American culture also assimilated German culture. Much of what we think of as “American” is actually German or strongly influenced by old German cultural values. Seeing as there was not always a unified Germany, but rather many German states, the German cultural influence on American main-stream society can include Belgium through the Netherlands and on into the Eastern State (Austria) and Prussia.