I love to travel across America . . . by postcard!

When I cannot actually get somewhere – or even if I do – I look for a beautiful picture postcard of the place. Not one of those overly bright and blue-sky-perfect cards made from cheap color slides, either. Even you and I can take better pictures than those. I like a touch of subtlety, a hint of surprise, in my postcard images, if you please.

In other words, I prefer old-fashioned picture postcards with a narrow white border, a grainy texture, and “that certain look” – somewhere between reality and somebody’s idea of art. What that look is, and how it came to be, is a fascinating story with lots of history and a little bit of technology. The history part, I think I can handle. We’ll muddle through the technical part together.

There’s a fancy word for the study and collecting of postcards. Don’t worry, I’m a beer-bottle guy, as you read in my last posting. But I do buy postcards, take a short trip down memory lane while looking at them, and then send them to others to enjoy.

That word for postcard-saving is “deltiology,” from the Greek, meaning a small writing tablet. With or without photos, postcards have always been just that: handy little rectangles of stiff paper on which to dash off a note. Where would the phrases, “Having a wonderful time. Wish you were here” be without them?

But it’s their flip side with the gauzy-looking photographs that’s maybe a touch out of focus – but pleasingly so – that I want to tell you about.

|

| This is art, not a photograph, of the horticultural hall at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. It, and plenty of photos, were made into postcards during and after the fair |

Picture postcards are bits of nostalgia, the size of your hand. Flights of fancy, too. I’ve been to Chicago many times, for instance, but never to the great World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and its “White City” that inspired a nationwide “City Beautiful” movement. But I can go to that great world’s fair via dreamy old postcards of its gleaming pavilions, inviting lagoons, and strolling visitors in old-fashioned bustle skirts and bowler hats and sailor outfits.

Nor, much as I get around, will I ever likely make it to a place like Picnic Rocks on the Kennebunk River in Maine. But I can study an intriguing photo of it, as long and hard as I want to, on an old postcard.

|

| This is the scene at Picnic Rock, at least as it appeared in 1900. There’s probably a four-lane highway or something there now! |

Vintage picture postcards are paper time machines, showing us how buildings and automobiles, cities and towns, and our people looked two turns of the century ago. You have only to look at an early postcard of the Denver skyline, or downtown Los Angeles, or the Model T Fords parked in front of a small-town saloon in 1912 to appreciate how much we’ve changed, if not progressed. And it’s almost as much fun to see that some of the landscape views in postcards of that period – the waterfall on Yosemite National Park’s El Capitan mountain for one – look almost the same today, except for the asphalt over the old dirt roads.

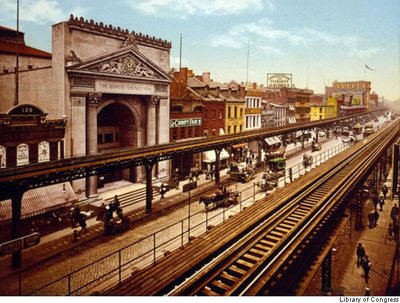

Lingering over the images, I imagine the slower pace of life, general optimism rather than today’s cynicism, the simplicity and gentility of life these cards depict. (And isn’t it interesting, that connection between the words “image” and “imagine”?) Cities seem so clean, the countryside so unspoiled, the people so prosperous and chipper. How carefree are frolickers on the beach in 1900 – at Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York, or Atlantic City, New Jersey – in their modest bathing suits that barely reveal an ankle.

|

| Coney Island, 1902. Nary a bare midriff to be found. |

Until 1898 in the United States, only the government produced “penny postcards,” costing one cent rather than the two cents you’d pay to mail a letter. No one else was allowed to. The business of “posting” at a “post” office was strictly an official matter.

|

| Art cards and advertising cards, like this plug for one company’s Valentine’s Day line, preceded picture postcards. Note the multiracial host of angels – unusual for the times |

But in that year, Congress authorized “private mailing cards,” which could also be sent for just a penny, at the very time that technology allowed incredibly skilled artisans to cover the fronts of these cards with actual photographs, not just woodcut sketches and artistic drawings. Little did Congress know that a stampede for the cards lay dead ahead, in a golden age era in which picture postcards would be sold and sent by the millions. According to the “Postcard & Greeting Card Museum” on the Web site emotionscards.com, “The official figures from the U.S. Post Office for [its] fiscal year ending June 30, 1908 cite 677,777,798 postcards mailed. At that time the total population of the United States was only 88,700,000!” That’s about seven postcards sent per man, woman, child, and even newborn in the country.

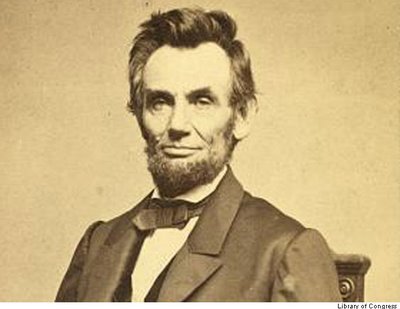

These pictures of which I speak were black-and-white at first. True color photography was in its infancy and far too expensive to translate to cheap mailing instruments. But evocative black-and-white photographs had been around since the 1860s and the daguerreotype era of the American Civil War, which we treasure today through the studio portraits and battlefield photos of Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and their cohorts.

|

| This was a portrait photo President Abraham Lincoln, taken in Mathew Brady’s studio in New York in 1864 |

In the 1880s Hans Jakob Schmid, a Zurich, Switzerland, printer, founded a company that licensed a process called “photochrom” (without the “e”) that enabled his fellow printers to produce a sort of color print. You’ll see why I say “sort of” in a bit.

|

| This is the rather modest entrance to a mighty business empire: the offices and plant of the Detroit Photographic Company, which produced the lion’s share of quality photochrom postcards |

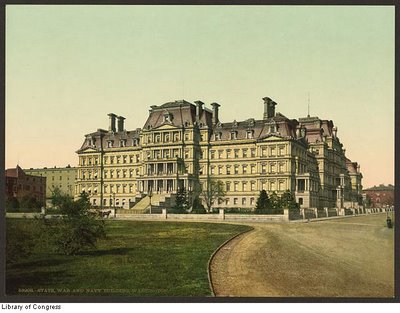

One of the most important photochrom licensees was the Detroit Photographic Company in the U.S. city of the same name. In some years during the picture-postcard boom, Detroit Photographic would produce as many as seven million prints of thousands of views from as many as 40,000 negatives. Some of them were destined for store catalogs, calendars, and advertisements.

But Detroit Photographic’s “bread and butter” was the production of postcards, which it sold mostly to gift shops and souvenir stands at popular tourist destinations, and to makers of catalogs aimed at what the Library of Congress calls “globe trotters, armchair travelers, educators, and others to preserve in albums or put on display.” Boxes resembling volumes of fancy bound books were available to store one’s photochroms.

|

| Detroit Photogaphic did not just make postcards of city and landscape scenes. It produced this photochrom of a bunch of California poppies |

Some were reproductions of works of art, but many were “scenics” of exotic locations to which only the most intrepid Americans would ever go. Detroit Photographic wisely bought the vast collection of images shot by an adventurous explorer and photographer named William Henry Jackson. He had been a government surveyor in the uncharted West, and he took along his camera. This was no easy matter, and not just because of the rugged terrain. Jackson’s cameras were bulky, heavy, and required fragile glass plates that he had to coat with gunk on the spot, out in the wild. Some of his 80,000 images of the American West, including one showing mist and fog caressing Colorado’s Mount of the Holy Cross, became postcard classics.

|

| The mustachioed fellow on the right in this family photo is William Henry Jackson – obviously duded up from his usual rugged outfit that he wore into the wilds |

Let me say that again: Working with cumbersome equipment in crude conditions, this one man produced 80 thousand images of the vast American West. He could not hop a flight to Cheyenne, rent a car, drive up paved roads to a comfortable vantage point – stopping at cozy roadhouses, comfy motels, and fast-food joints along the way. Horses were his rental cars. Logging roads were his highways. Bedrolls beneath the junipers were his sleeping quarters. Each photo-shoot site was many days from “civilization.”

|

| This is one of Jackson’s burro shots. These surefooted animals hauled all sorts of materials up and down the Rocky Mountains |

And Detroit Photographic sent him out again. He brought back more images of cowboys, American Indians, and animals, including burros dragging lumber into mining camps, high in the Rockies. Jackson got no credit on any of the picture postcards, but hard-core postcard aficionados knew him and his work well.

Jackson lived to be 99. In his last years, he painted murals in government buildings, including scenes of (you guessed it) the Old West on the walls of the Interior Department Building here in Washington. One of the last surviving Civil War veterans, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River in Virginia.

Let me remind you of something. Jackson’s shots – indeed the whole archive from which Detroit Photographic produced pretty postcards – were in black-and-white. It took the miracle of the photochrom process – at least I consider it miraculous – to turn those images into the vivid, color picture postcards I and many others love today.

|

| This is a before (b&W) and after (color) look at the same image of American flag-maker Betsy Ross’s house in Philadelphia |

So get out your pencils for the technical lesson on how this was done, at least as I, hardly Mr. Science, understand it. I am guided by, and borrow heavily from, what might be called a “Lithography for Dummies” short course, genially delivered by telephone by Terry Belanger, director of the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia.

Belanger asks us to picture a piece of “shirt cardboard.” Not the kind you’ll find inside a new, folded man’s shirt when you buy it at the store, but a thicker, absorbent cardboard around which commercial laundries used to fold shirts. He then directs us to imagine a big “X” drawn on that cardboard with a wax candle. Next, we wet the cardboard thoroughly. We will quickly note that the water soaks into most of the cardboard but – on the old “oil and water don’t mix” principle – is repelled by the waxy “X.” If we then take a spongy roller, soaked in oily ink, and roll it all over our piece of cardboard, then press a piece of paper against it, a pretty good image of the letter X will appear on the paper. We can repeat this process over and over again to make multiple copies of our X.

Pay attention now. It gets trickier, but more interesting. The same principle applied to making photochromatic postcards using “stone lithography.” (Here we go again with the Greek: lithography from “Lithos,” or stone, and “graphein,” meaning to write. Lithography is writing in stone!) Instead of our shirt cardboard, the folks at Detroit Photographic started with a flat surface made of porous limestone that they coated with a sticky, black, hydrocarbon substance called bitumen, thinned with benzene to make it spreadable. (Imagine the fumes!)

This porous limestone slab is the lithographic stone.

Bitumen is highly light-sensitive. The black goo hardens in direct proportion to the length of time, and intensity, of exposure to light. Next, a black-and-white photographic negative – say one of William Henry Jackson’s big, 20×25-centimeter beauties – was pressed against the gooey stone, and the whole thing taken outside into the daylight. There it all sat for just minutes under a hot summer sun, but sometimes hours on a gloomy winter day.

The daylight “did its thing”: hardening the bitumen underneath the film. Remember, these were negatives; reversed. Dark places on the film – say a tree trunk – would be nearly clear, allowing lots of light to get through to the bitumen. Light places like a bright sky would be dark, so less light would shine through to the concoction on the stone. The stone would cook in the light until the bitumen in the dark spots (that tree trunk) had fully hardened, while the sky and other lighter parts had not fully hardened.

The negative was then removed, and the bitumen coating washed in a turpentine solution. This removed all the glop, leaving some bitumen where it had not completely hardened, and all of it where had turned solid. The result was a finished stone, of which Detroit Photographic had thousands, each numbered and stored in racks, all around its production floor.

If the printers had been satisfied to stop at this black-and-white stage, that would have been pretty much it. They could have inked up the stone, run paper across it, and out would have come lovely prints that looked just positive versions of the images in the negatives – with one interesting exception:

They would be backward! If a moose in the photograph were looking off toward the right, it would be looking left on the print. If the entrance to a building were on the right as you faced it in real life, it would be on the left on your page. It took me about 20 minutes to completely figure out why. You don’t have the time. The bottom line is that when it mattered that right was right and left was left, the printers simply flipped the negative when they first put them on the goopy stones. Then the prints came out just as the scene looked through the photographer’s lens.

The big question before us, though, is: How did the printers produce color, when everything including the film was in black-and-white? I take it you’re ready for the advanced class!

Employees at Detroit Photographic would make six or so different stones. One would be the full, black-inked one that we’ve described. But they would also look carefully at the black-and-white image and single out parts of it that were, for example, likely green in real life. Grass. Leaves, that sort of thing.

I say likely, because some of this was guesswork, since these fellows had almost certainly never laid eyes on the places shown. They were pretty sure, though, that grass was green, the sky blue or grayish blue, deer and dogs brown, and so on. Doors and clothes, advertising signs and the color of people’s eyes? That was educated guesswork, and a chance for a little creativity.

Having already made the image on the lithographic stone, the artisans would make several impressions of it on paper, using water-based black ink. Then on six or seven smooth, clean stones, they’d lay those damp impressions, transferring the impressions of the entire scene to each of those stones.

Let’s suppose that in, say, a photograph of Pikes Peak in the Colorado Rockies, only a tiny piece was yellow. The ball of the sun, we’ll say. Bending over one of the wet stones containing the entire image of Pikes Peak and environs, the printer would apply a dab of oil-based bitumen in that little spot and that spot alone. After the bitumen dried, he’d wash the water-based ink off the stone. Only the dot of oily bitumen where the sun appears in the photo was left. The printers would do the same thing with other parts of the scene, excising all but the sky and a lake, we’ll say, on the blue stone, and so on.

Then it was time to print, using all six or seven stones. They’d coat the “yellow” stone – the one on which only the dot for the sun remained – and run or press paper over it. All that would show on that paper was little dab of yellow. Then the paper was pressed to the red and blue and green stones, etc., with their partial images. Last came the run with full image in black.

The result was a surprisingly vivid spectrum of color, all in the right places. This was tricky on several fronts, not only making the color as realistic as possible. It was also tough to run the same paper over so many stones, none of which was precisely the same dimension, and produce a clear and unblurred final image. If one stone, say the one inked in red, was a hair out of alignment, the result could be a postcard that looked out of focus. Thus, there many test runs. And clarity or fuzziness would become one barometer to tell quality work from slipshod efforts.

Since these early photochroms from which postcards were printed were not true to life but were interpretations, they have a look all their own. I happen to love their unnaturally lemon suns, their extra-black stormy skies, and their unusually bright-pink flowers. The effect is not so contrived as to be jarring. Instead, it’s a remarkable achievement, as you may agree when you look at the ones on this page. It’s hard enough to imagine “colorizing” a black-and-white picture by hand in the sort of “paint by number” fashion. It’s quite another to realize that these artisans brought out subtle color differences in complex scenes using a big-old printing press.

|

| Check out the beautiful color of this 1903 photochrom of a Ojibwa Indian named “Arrowmaker.” Remember, this started as a black-and-white photograph |

In today’s times of ultra-reality, multi-megabyte photographic fidelity, and high-definition TV, you may find old postcards cheesy and amateurish. But I can assure you that the millions of people who bought and sent them in 1900 and a few years beyond thought they were state of the art.

Several developments damaged, but did not entirely kill, the picture-postcard business. Many of the most desirable cards had come from Europe and showed exotic foreign scenes. With the advent of World War I in the 19-teens, that source was greatly diminished. Wartime at home cut into the printers’ workforce and the quality of the cards. And most of all, the telephone replaced the simple postcard as the preferred method of quick communication.

“Real-photo” postcards, the first that were photographic reproductions, not layered and colorized prints of black-and-white photos, came along. But as I said early-on, to me they look like something Cousin Bill would produce with his Kodak, rather than creative works of the printing art.

Give me an old photochrom, especially a smudged, canceled one with a century-old message from Bertha that she’s having wonderful time and wished husband James were there.

|

| Talk about a dreamy scene! This photochrom image depicts a riverboat turning the bend on the swampy Oklawaha River in Florida |

Over in the right-hand column this time, instead of the usual gallery of some of Carol M. Highsmith’s current images, Web guru Anne Malinee and I have assembled two related slide shows. The first is a series of photochrom images as captured by the excellent Prints & Photographs Division at the Library of Congress. As I’ve explained, it was these and ones like it from which early color postcards were printed. The second is a series of actual postcards that Carol photographed and digitally scanned. You won’t notice a great deal of difference – a little more fuzziness in the postcard group, perhaps, as they were taken from off the rumpled postcard paper rather than film. We thought you’d enjoy a chance to savor some of the wonderful old scenes, as we do.

One other quick matter this post, and I go there only because it, too, involves impressive old photographs.

During the 1930s, the United States Government, under the auspices of one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” agencies called the Farm Security Administration, sent photographers across the country to document the severe of the Great Depression. Roosevelt wanted ammunition for still more New Deal relief efforts. Many of the classic photos of unemployed workers, and especially farm families displaced by drought conditions, were produced by Dorothea Lange, a onetime San Francisco portrait photographer.

|

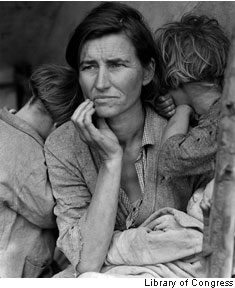

| This the iconic “Migrant Mother” photo that spellbound the nation during the Great Depression. Her daughter Katherine, mentioned in my post, is the little girl on her mother’s right – our left |

Her most famous photo – indeed the shot that became the symbol of those grim times – was taken in 1936 in a California resettlement camp. It showed a woman, Florence Owens Thompson, whom Lange called “Migrant Mother” flanked by two of her young daughters.

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange later wrote. “I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. . . I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

I mention this because not long ago, the American cable-news channel CNN found one of the two daughters shown with their mother in the Migrant Mother photograph. Katherine McIntosh, now 77, was 4 at the time. She says the photo was printed in a local newspaper the next day, but the family of eight – she and her mom and six siblings – had moved on. “The picture came out in the paper to show the people what hard times was,” McIntosh told CNN. “People was starving in that camp. There was no food. We were ashamed of it. We didn’t want no one to know who we were.”

Instead, nearly everyone in America soon knew who they were. In 1998, the image even adorned a 32-cent postage stamp. Thompson had died of cancer and heart ailments 15 years earlier. And the image of her, Katherine, and Katherine’s sister Norma lives on. Original photographs of the “Migrant Mother” image have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars at prestigious auction houses.

Thompson and the kids could have used just a fraction of that amount back in the day.

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Bustle. This has two quite different meanings. To bustle is to move briskly. As a noun, the concept is often paired with a word with which it rhymes. We speak of the “hustle and bustle” of a city. But as used in my posting, a bustle was a wire frame, or a pad, or even a bow, at the back of a woman’s skirt that accentuated its fullness.

Cheesy. Cheap. Poorly made. It derives from an Urdu word adapted by the British to mean showy. From there, the meaning declined even further to reflect something even more derogatory that has nothing at all to do with cheese.

Chipper. Cheerful, upbeat, self-confident. Chipper people break into a whistle from time to time. Those in a less buoyant mood can find them annoying.

Deprivation. Extreme poverty. A state in which one is deprived of even the basics of life. Be careful with this word. “Depravation,” spelled with the “a” instead of the “i,” means moral decay and degeneracy. That version is an offshoot of the word “depraved.”

Please leave a comment.

One response to “Pretty as a Picture . . . Postcard”

fellow..

I’m not an excellent into reading, but somehow I got to look atmany content material within your webpage. Its wonderful how helpful it is for me to go to you incredibly typically.