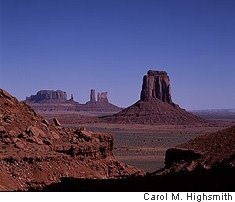

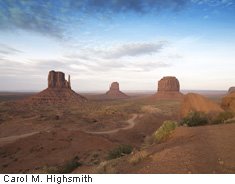

Only one lonely, two-lane highway pierces Monument Valley, a vast natural wonder that straddles the Arizona-Utah border in the Desert Southwest. And then one unpaved, rutted, 27-kilometer [17-mile] loop trail winds through it once you get there.

|

| Stubs of sandstone jut upward like broken lower teeth on Monument Valley’s desert floor |

The air is clear there and often scalding hot, the desert floor still wild, and the red-rock formations that seem to march in review will take your breath away.

Until this spring there was but one motel anywhere nearby – an old lodge that advertises “refrigerated air conditioning,” “iron and ironing boards,” and “bathing amenities.” You can rent John Wayne movies if you stay there. That’s significant, because more than anyone, that rugged star of epic western movies brought attention to this remote, prehistoric time capsule. More about “the Duke” in a bit.

Now that that paved road passes nearby, a new inn has opened right at the entrance to the eroded old loop trail, and people like me have spread the word about the stunning spectacle of buttes and spires, the days of undiscovered desolation for Monument Valley are gone forever.

|

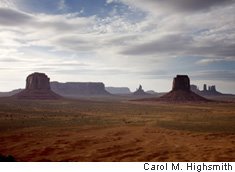

| East and West Mitten buttes take their place among the formations |

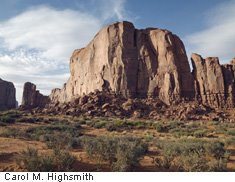

Unlike the Grand Canyon off to the west in Arizona, whose beauty emanates from the cliffsides of a single, awe-inspiring gorge, or Arches National Park to the north in Utah, where one must hike to see many of the amazing formations, Monument Valley’s rocky “Mittens,” “Three Sisters,” and other towers of red rock rise in a staggering panorama that can be visited and photographed up-close as well, via that dusty trail.

|

| The “Three Sisters” spires poke out of the desert |

For Carol and me, it is Monument Valley more than any of the other spectacular parks that pulls us back to the Southwest for another look, and then another, as the sun paints each formation, turning dark silhouettes a dappled sepia, then fiery crimson depending on matters as mercurial as a passing puffy cloud. To the Navajo people who live here, this is a sacred place, a shrine to Mother Earth and Father Sun. To them – and others who come from the world over to behold it – it is Nature’s might and God’s artistry entwined.

“Nowhere in the world can one find a similar effect of nature’s work,” wrote Josef Muench, the German-born photographer whose work turned Arizona Highways from a travel magazine into a catalog of landscape art. “Words alone cannot begin to describe the thousand-foot pyramid and castles, the slender tower, bridges and arches that dominate Monument Valley.”

|

|

Believe it or not, the sandy path that looks like an expanse of beach is the ROAD that ordinary vehicles travel through the heart of Monument Valley |

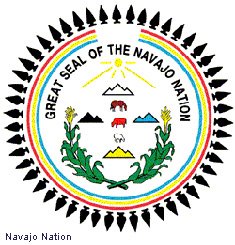

Like the Grand Canyon, Monument Valley is a national park. But the nation is not the United States of America. Monument Valley is the jewel of several Navajo Nation tribal parks within the vast, three-state, largely sovereign homeland of the Diné – “the People” – as the Navajo call themselves. (It’s clear why they use another name: “Navajo,” assigned to the tribe by the Spanish, traces to a word that means “thief.”)

And the story of Monument Valley is tied inextricably to the Navajo people and their history.

At 70,000 square kilometers [27,000 square miles], Navajoland, as the Diné like to refer to what whites once called the Navajo Reservation, is larger than 10 of the 50 U.S. states. It is also the largest Indian nation in both size and population (174,000). Another 75,000 Navajos live elsewhere, including large cities like Arizona’s capital of Phoenix.

|

| These Navajo Code Talkers were photographed on the island of Saipan in 1944 |

People the world around have heard of Navajos because of their singular contribution to the Allied victory in World War II. Navajo Code Talkers joined every landing and parachute jump by U.S. Marines in the Pacific theater of war. Once ashore they transmitted messages by telephone and radio in their native language, baffling the Japanese, who mistook it for a secret code that they never succeeded in cracking.

|

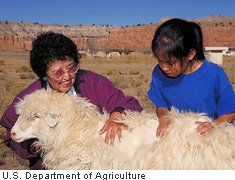

| A Navajo mother and daughter inspect the long, thick fleece of a Churro sheep |

But the world is coming to know the Navajos of Monument Valley as well. “Navajos are nomads and adaptors,” writes K.C. DenDooven, publisher of the “Story Behind the Scenery” series of interpretive books, including a new one on Monument Valley. “They live by their rules and at their own pace – both of which in many ways are distinctly different from the white man’s. Sheep and wool [and the intricate Navajo rugs made from wool] are one of the main forms of industry throughout the entire Navajoland. Sheep wander. Navajos wander.”

|

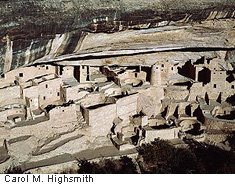

| The ancient Anasazi built cliff dwellings throughout the Four Corners area. This one can be found at Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado |

Their ancestors, Athabascan people who first crossed the Bering Strait from Asia into present-day Alaska and Canada 35,000 years ago, eventually migrated southward into barren lands that are boiling hot each summer and cold enough to dust the sandstone with snow each winter. Like us today, they came upon remnants of an earlier, mysterious native culture that we have named the Anasazi – Navajo for “ancient ones” – who built homes on the cliffsides, carved rock engravings called petroglyphs, and created painted pictographs.

Then they disappeared without a trace. Driven to starvation by the harsh conditions perhaps, or driven out by marauders.

|

| It’s hard to believe this “painting” is made of loose sand |

The Navajo paint, too, in sand paintings using bright pigments ground from the rocks, as part of the healing ceremonies of medicine men. When the rituals are completed, the paintings are destroyed and the sand disbursed.

|

| Navajos weave and dye their own woolen rugs in a multitude of hues |

Navajo clans dotted the remote hills of what is now northern Arizona and New Mexico with little cohesive government. That changed with the coming of Spaniards in the 1500s. Bent on colonizing the area for New Spain (Spanish-controlled Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean and the distant Philippines, run as a viceroyalty from Mexico City), the Spanish sent out soldiers and missionaries. But the nomadic Navajos proved to be elusive converts, resisting Christianity, the Spanish language, and any notion that they would meekly settle down and tend to crops. The Spaniards’ fortunes dimmed further when the Navajo stole their horses – they were thieves indeed in that instance – and used them skillfully to elude and bedevil their would-be conquerors. When the Spanish proposed treaties, not one Navajo entity or spokesman could be found to agree.

So the Navajo held out, beyond Spanish control or that of the Mexican Empire that succeeded New Spain in 1821.

But the U.S. territorial government that came next had greater resources, and therefore better luck, in its series of “Indian Wars” against the Navajo and Apaches. In 1862, Gen. James H. Carleton, commanding U.S. forces in Arizona and New Mexico, decided that it was time to put an end to the “Indian troubles.” As the SouthernNewMexico.com Web site puts it, “His plan was to put [native peoples] on a reservation under military guard, teach them farming and livestock raising to encourage self-sufficiency.” Carleton ordered Col. Christopher “Kit” Carson, a legendary western scout and frontiersman who thought he had settled into peaceful retirement in New Mexico, to round up Navajos and Apaches, kill any who resisted, and bring the captives to Fort Sumner at Bosque Redondo (“Round Wood”), an Indian reservation and trading post in southern New Mexico.

|

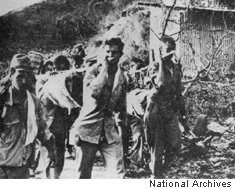

| It’s estimated that one in four U.S. and Filipino soldiers driven along the Bataan Death March did not survive the brutal ordeal |

White soldiers killed the livestock of each Navajo family, who were then ordered to chop down every tree and cut their wheat and corn. Starved into submission, the Navajo were marched at gunpoint in what the Diné call “The Long Walk” from their homeland to Bosque Redondo. It was a journey that one day would be compared to the earlier Trail of Tears following the “Indian Removal Act” of 1831 that uprooted eastern Indians and prodded them on foot to reservations in Oklahoma, and to the Bataan Death March of captured Americans and Filipinos by Japanese soldiers in the Philippines during World War II.

Any trust that the Indian people of the American Southwest had invested in whites before Bosque Redondo was replaced by hatred, suspicion, and defiance – attitudes that linger, in varying degrees, to this day.

Only 6,000 Navajos survived the Long Walk, though others fled to hide in the Grand Canyon and elsewhere. The captives faced a difficult choice between accepting “civilization” and white ways, or extinction. Exclusion and segregation onto reservations, not assimilation into the larger culture, were official U.S. policy for the “red man.”

An unidentified Navajo, quoted on SouthernNewMexico.com, wrote in 1865:

|

| Indians who survived the Long Walk gather near the Bosque Redondo trading post |

Cage the badger and he will try to break from his prison and regain his native hole. Chain the eagle to the ground – he will strive to gain his freedom, and though he fails, he will lift his head and look up at the sky which is its home – and we want to return to our mountains and plains, where we used to plant corn, wheat, and beans.

So many Navajos died of dysentery, malnutrition, and, metaphorically, heartbreak at Bosque Redondo that the U.S. Government abandoned its attempt to “civilize” them. The government signed a peace treaty releasing the captives. At dawn on June 18, 1868, a column of 7,000 Indians, 1,500 horses and mules, 50 Army wagons, and 2,000 sheep stretching 16 kilometers [10 miles] long left Fort Sumner. It was the Navajos’ Long Walk in reverse, this time without hostile armed escort, back to their homeland in northwestern New Mexico and northeastern Arizona.

|

| This Navajo brother and sister were photographed, reluctantly it would seem, in 1915 |

There, they would have the hard land much to themselves for decades to come. An occasional prospector passed through, unsuccessfully looking for gold or silver. Archaeologists and anthropologists descended upon Anasazi cliff dwellings. And collectors’ agents plundered the ancient sites. But the region’s harsh climate and nearly bone-dry terrain held no long-term appeal to white settlers.

|

| Did we say “harsh”? Of course, Carol’s photo was shot on infrared film, which exaggerates the terrain’s extremes |

In 1923, a white sheep rancher named Harry Goulding and his wife, whom everyone called “Mike,” moved into the valley. They would build a trading post from which to sell supplies, Indian rugs and jewelry, including rings and necklaces made of turquoise, the robin’s-egg-blue gemstone that is one of the Navajos’ sacred stones. For centuries, Navajo hunters have worn turquoise to bring success, shepherds donned it to assure the fertility of the flock, and warriors carried it to inspire victory.

|

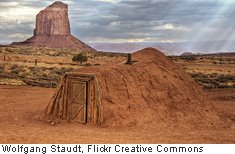

| The hogan is the pragmatic but extremely modest traditional Navajo home. It’s made from the crude and scarce materials available |

According to K.C. DenDooven’s account, the Navajos who helped Harry Goulding construct his lodge had never before seen a two-story stone building; their people lived in hogans – always east-facing toward the morning sun – made of wooden poles, tree bark, and mud. Navajos would later move into modest trailers or small houses, but they continue to build hogans for religious ceremonies and tourist demonstrations.

The Gouldings’ trading post still stands, more as a museum next to the old motel that I mentioned. But the Navajos’ wool, once delivered to Harry’s place by horse and wagon, is now carried to fair-sized towns by pickup truck. From time to time, sheep and goats are also herded along the park’s sand dunes for the benefit of tourist photographers.

Business was anything but brisk at Goulding’s Trading Post in the 1930s. The only roads were old, pitted trails. Monument Valley lay unnoticed to just about all whites except the Gouldings and Muench the photographer.

But one day, Harry Goulding told Muench that they should gather some of his black-and-white photos – the technology to produce today’s stunning color shots hadn’t yet been perfected – and drive to Hollywood, over in California. And that they did. There, they spread a photo album before producers who had been filming barely-believable “westerns” in the California desert or on contrived back lots. Surely, Goulding and Muench told the movie moguls, a rugged-rock backdrop of the real West would be an improvement.

John Ford, already a noted screenwriter and director who had delivered a silent western spectacular, “The Iron Horse,” about an early railroad across the West, and his production chief, Walter Wanger, were sold on the spot. (However, after Goulding and Muench left, Ford dispatched an aide to fly over the area to verify that the valley looked as astounding in situ as it did on film.) By the time Goulding and Muench reached Williams, Arizona, 300 kilometers (186 miles) from Monument Valley, on their trip back home, crews had already descended, buying food and other supplies for the first film shoot.

|

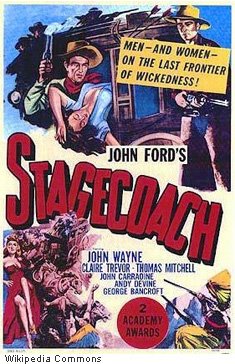

| Besides John Wayne, notable “western” regulars Thomas Mitchell, Andy Devine, and John Carradine appeared in “Stagecoach,” along with several Monument Valley scenic shots |

The result was the classic 1939 western “Stagecoach,” starring John Wayne in his breakthrough role as the Ringo Kid. It was Ford’s first “talkie” western and the first of ten he would film on location in Monument Valley. The plot concerned “men and women on the last frontier of wickedness!” enduring a harrowing trip by stage across dangerous Apache – not Navajo – land. (“These hills here are full of Apaches. They’ve burnt every ranch building in sight!”) The surroundings looked appropriately stark.

In the long run, Monument Valley’s panoramas, as much as famous actors, were the stars of “Stagecoach” and other movies filmed there, bringing the park’s red-rock splendor from obscurity into the world’s imagination. There’s now a “John Ford Point” in Monument Valley, marking a spot from a scene from “The Searchers,” supposedly set in Texas but filmed in Ford’s favorite Navajo valley. Jack Nicholson and Dennis Hopper rumble through Monument Valley on their motorcycles in the 1969 counter-culture

|

| Many a Hollywood actor, or perhaps a stunt man or woman “double,” has driven one sort of vehicle or another down the dusty road through Monument Valley |

classic, “Easy Rider.” In “National Lampoon’s Vacation,” the Griswold family’s station wagon falls apart in a most unfortunate place: forbidding Monument Valley. Stanley Kubrick picked a perfect spot for an alien planet’s bleak terrain in his “2001: A Space Odyssey.” It was, of course, Monument Valley. Tom Cruise even climbs a Monument Valley spire in “Mission Impossible II,” a practice that in real life is sternly prohibited by the Navajos in this sacred place.

Lots of TV shows and music videos have been shot in the valley as well, all thanks to Harry Goulding and Josef Muench’s sales pitch.

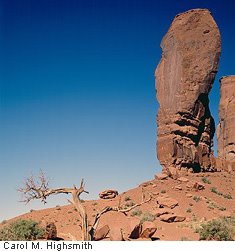

Some of the visuals shot in Monument Valley, including those of visitors lucky enough to arrive in early spring, show the rabbitbrush, cliffrose, aptly named snakewood bush (rattlers, you know), scarce cottonwood trees, and the purple sage – after which Zane Grey’s best-known western novel and the country-rock group “New Riders of the Purple Sage” are named – are in vivid bloom. Many of them spring to life again, fleetingly, after a summer deluge and flash flood. Otherwise, they lie dormant beneath the sizzling sun.

But the red rock, blue sky, white clouds and occasional snow, raging black thunderheads, and flat-green brush supply plenty of color without them.

|

|

Monument Valley sunsets are worth waiting for |

Monument Valley is, of course, a prime geological exhibit. For hundreds of millions of years, sediment eroded from surrounding mountains coagulated into a vast table of solid sandstone, 300 meters [1,000 feet] deep, spread over 259 square kilometers [100 square miles]. Then came a slow geological uplift that turned what had been a basin into a

|

| You can see many geological folds, layers, and striations in this up-close view of a Monument Valley formation |

high plateau. And once again millions more years of erosion followed. They left behind the hardest slabs and slivers of rock, looming as pinnacles, buttes, and arches above the land that we know as Monument Valley. I say “know as,” because it’s not really a valley at all! It’s a sweeping plain without many surrounding mountains but punctuated with those magnificent red-rock formations.

But neither the rocks nor their gorgeous depictions in western movies brought many outsiders to Monument Valley until the 1940s, when the main road from Kayenta, Arizona, up into Utah was finally paved. Miners came to extract uranium but left after 20 years when the veins played out. Still, 11,000 tons of ore containing “yellow-cake uranium” mined there would supply the Manhattan Project – the top-secret, all-too-successful effort to build an atomic bomb in the desert next door in New Mexico.

|

| The Navajo’s traditions and humble lifestyles haven’t changed much since this photo was taken in 1915 |

All the while and afterward, the Navajos stuck to their sheepherding and crafts – a proud but meager existence. Today, according to the Utah Department of Community and Culture, “Despite its significant economic potential, socio-economic conditions on the Navajo Nation are comparable to those found in some underdeveloped third world countries.” About 55 per cent of the Navajo people live below the poverty level compared to 12.8 percent for the United States overall. A Navajo’s average annual per capita income is about $6,000. It’s $47,000 nationally. Unemployment in Navajoland ranges from 36 percent in tourist and crop season to more than 50 percent each winter. And in another measure of the bleakness of one’s days in this barren but beautiful land, there are, even today, just 3,200 kilometers [2,000 miles] of paved roads in all of the Navajo Nation; West Virginia, a relatively remote and rural place of about the same size, has nine times that much good roadage.

As tourists slowly but insistently began to come calling in Navajo land in the late 1960s, the Navajos tightened their organizational structure, changing their designation from Indian tribe to Navajo Nation and asserting even greater control over their economic and political life.

|

The Navajo Nation’s sovereignty from U.S. control, yet coexistence with the states and federal government around it, are embodied in its official seal. It displays 50 arrowheads – representing the U.S. states – in an unbroken circle around a drawing that shows four great mountains that border Navajoland, and three species of livestock.

Responding to increased tourist traffic, the Navajos set up a small souvenir shop and a gatehouse at which a $5 fee to enter the dirt loop road is collected. Tribal members increased their horseback and wagon tours to hidden parts of the park, including a place called “Mystery Valley” that contains Anasazi pueblo ruins and rock art such as a petroglyph of a sheep.

It became clear to many visitors that Monument Valley equals or surpasses the scenic grandeur of better-publicized and more accessible U.S. National Parks, and we have all wondered why it never became one.

The answer traces to Navajos’ national pride, plus their lingering suspicion and defiance of whites.

As I’ve noted, few outsiders had discovered Monument Valley before John Ford and his film crew arrived. But Roger Toll had. He was the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, the original U.S. national park far to the north in Wyoming. In 1931, he was dispatched by federal authorities to traverse the West and identify sites where national parks could be established before developers gobbled up the land. He showed up in Monument Valley and was, not surprisingly, “blown away” – to use today’s vernacular – by what he saw. Toll wrote a report that enthusiastically recommended creation of a vast new national park there. It noted that the State of Arizona and the U.S. Indian Service, predecessor of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, would no doubt be thrilled with this addition to the nation’s scenic attractions.

He said nothing at all about what the Navajos might think.

Toll’s plan proceeded cheerfully through the federal bureaucracy. Patronizingly, it stipulated that local Indians could continue living – no doubt far away from tourists – in the new park, and they could keep their sheep, too. No doubt they’d prosper, relatively speaking, as seasonal park hands.

Congressional approval seemed certain, and the relatively compliant Navajo Tribal Council signaled that it, too, would go along.

|

| Perhaps inspired by this notable upcropping, Roger Toll gave an enthusiastic thumbs-up to the notion of a Monument Valley U.S. park that never materialized |

But in a stroke of truly bad timing, the new U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier, showed up in Tuba City, Arizona, the Navajo Reservation’s largest city, 120 kilometers [75 miles] from Monument Valley. He carried a startling new mandate for the Navajo people. To curb what had become a serious problem of overgrazing in the sparsely vegetated area, Collier ordered a “stock reduction” program. It cut the size of many Navajo sheep herds by half or more, resulting in even greater destitution – and documented starvation – among the Navajo people. As one U.S. Park Service history concluded, “No event since the exile to the Bosque Redondo was more demoralizing. . . . The Navajos became suspicious of any government program . . . as a threat to the Navajo way of life.”

So suspicious that the Navajo Tribal Council angrily rejected the Park Service’s plan to create a dandy new national park in and beyond Monument Valley.

The opening of The View, the Navajo Nation’s new motel and visitor center from which tourists can take decent, if distant, panoramic photos of Monument Valley’s formations, illustrates a predicament for the Navajo people: a tug-of-war between traditional ways geared to livestock herding, rug weaving, and the spiritual power of the surroundings; and the forces of modernity, including tourist money and what it can buy. Even 18 years ago, a report about the U.S. Park Service’s Navajo National Monument, not far away, observed, “A recent trip to Farmington Mall [over the state line in New Mexico] revealed scores of young Navajos in the classic garb of the generic teenager: unlaced tennis shoes with the tongues hanging out and heavy metal T-shirts of popular groups. The demands of the modern world have an overwhelming character. They hegemonize indiscriminately.”

|

| The Navajo Nation flag was designed by J.R. Degroat, a New Mexico Navajo. It was selected over a 139 competitors in a contest and adopted in 1968 |

Standing on that balcony, watching visitors’ cars inch their way along the torturous dirt road through Monument Valley, Carol and I lamented the day that is almost sure to come, when – for the “convenience” of visitors, that road will be paved, and then widened, and then, perhaps, interspersed with gas stations and convenience stores and a gaudy Indian casino. When that day arrives in a place that is holy to the Navajo and serene to everyone who beholds it, honking cars and lines of campers, crowded overlooks, clouds of CO2, and scraps of litter tossed at the great rocks and stuck in the trees will have turned Monument Valley into America’s latest paradise lost.

While We’re There

I should also mention three other remarkable places to see within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation.

Two are national monuments, administered by the National Park Service.

|

| These cliff-dwelling ruins at Navajo National Monument overlook Betakin Canyon |

Navajo National Monument protects what’s left – after serious erosion and the depredations of relic thieves – of three cliff dwellings of ancient puebloan people. Access is along short, self-guided trails.

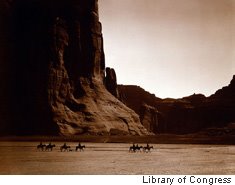

Canyon de Chelly National Monument also features cliffside Anasazi ruins. They can be viewed from the opposite rim, but access to the canyon floor is restricted to tours by park service rangers or Navajo guides. Inside the canyon, two towering sandstone spires that together are called Spider Rock have been the setting for a number of television

|

| Seven Navajo riders and a dog cross the Canyon de Chelly in this photograph, taken about 1904 |

commercials. According to Navajo beliefs, the taller of the two is the home of Spider Woman, sometimes called the “Spider Grandmother,” who threw a web laced with dew into the sky, creating the stars. De Chelly, pronounced “de SHAY,” is a combination of Spanish and Navajo words meaning “inside the rock,” as in finding oneself in a tight canyon surrounded by high, red bluffs.

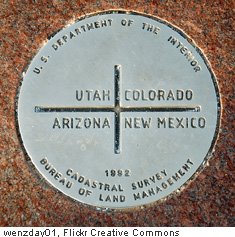

My favorite, outside of Monument Valley, is Four Corners, the only place in America where four states – Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah, touch. It takes forever and half a tank of gas to reach, but it’s one of those places where you feel compelled to get a picture, no matter what it takes to get there.

Even if there isn’t much of a there there.

|

| We’ll show you this tasteful photo of the point where four Southwest states come together, rather than the disgusting one of me trying to position myself in all four at once |

All of the four abutting states would surely have ignored the place had the Navajo not set up a modest monument, ringed by flags of the four states and a few sorry shacks from which one can purchase jewelry, a cold drink, or fried Indian flat bread. Criss-crossed lines on a U.S. Department of the Interior marker denote the convergence point of the four states. Of course, tourists cannot resist turning themselves into quadrupeds, down on “all fours”: left hand in Utah, right hand in Colorado, right foot in New Mexico, left foot in Arizona, and dignity out the window.

I remember my remark to Carol in that circumstance: “Yes, I know I look stupid. Just take the photograph!”

Hold the Croutons

One last thing, completely off the subject:

If you’ve followed these postings, you know that I like to note the passing of those who have done interesting things, whether or not the person has reached the threshold of fame.

Norman Brinker, who died on June 2 at age 78, was such a guy. Norm had an important influence on my life, at least as of late. He is credited with having invented . . . the salad bar! . . . that long table of fruit and veggies that might have been good for you if you hadn’t heaped on bleu cheese dressing, sunflower seeds, bacon bits, and maybe a glop of chocolate pudding from the “dessert bar,” squeezed into a crevice in the mound of food on the plate.

In the 1960s, Brinker started a chain of casual “Steak & Ale” restaurants in which he gave customers the option to fix their own salads or even make a main course of them. So, a tip of the lettuce tongs to Norm!

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Depredations. The ravages left behind by plunderers or marauders.

Forbidding. Stark, rugged, even life-threatening.

In situ. In its full and natural setting. Someone commissioning a photograph of a gate, for instance, might ask that it be captured in situ, including the fence and landscape that surround the gate itself.

Traverse. To cross or pass through a place. The word’s root is the same as the root of “travel.”