“Time will show that this is the most important law in our culture over the last 40 years,” USA Today columnist Christine Brennan wrote recently.

The most important? That must be some kind of law!

Brennan is a sports columnist specifically, and like it or not — and there are plenty in both camps — the law to which she refers has profoundly changed the nation’s sports scene.

Yet the word “sports” never appears in its language.

The law, passed in 1972, is known as “Title IX.” It was one of the amendments to what is now called the “Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act,” after its author, the late Hawai`i congresswoman who as a young woman had faced several obstacles in her quest for a college degree. A few days ago at the White House, various speakers marked Title IX’s 37th anniversary.

“No person in the U.S. shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded in participation in, or denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving federal aid,” Title IX reads.

|

| Most American high school and college team photos were a strictly male affair from early days until not too long ago |

In 1972, according to the National Women’s Law Center, fewer than 32,000 women participated in intercollegiate athletics, and women’s sports programs received just 2 percent, nationwide, of colleges’ athletic budgets when the law was signed. In the eyes of the bill’s backers, this was an obvious and raging inequity. And since just about all colleges and public school systems receive federal funding, the national government was in a position to try to correct it.

Nothing less than fully equal opportunities for both sexes would be acceptable.

When it came to sports, the U.S. Department of Education interpreted the mandate to mean that young women should have the same level of equipment, practice time, quality of coaching, facilities and housing, and even publicity. And of most concern to the women athletes, they should have the same access to financial assistance in the form of athletic scholarships as well.

|

| College and even high school football are expensive, but lucrative, spectacles. This is a Clemson University game |

Since football, in particular, is played almost exclusively by men and is a terribly expensive sport to field, the government did not require an absolute 50-50 split of all athletic expenditures on college and high-school campuses. But schools could not use the high cost of football to justify denying women full access to sports of their choice. In fact, the law demanded:

|

| Title IX is predicated on women and girls’ right to experience the satisfaction and joy of athletic competition |

• “athletic opportunities that are substantially proportionate to the student enrollment” — an enormous hurdle for institutions where lots of women are enrolled but which had barely given women’s sports a thought;

• OR “continual expansion of athletic opportunities for the underrepresented sex” (women, almost always) — a bit more do-able;

• OR “full and effective accommodation of the interest and ability of the underrepresented sex” — open to considerable interpretation.

|

| Title IX had no impact on the number of cheerleaders, pep squad members, and majorettes, of which there were already plenty |

After several class-action lawsuits and demands by the education department, the average U.S. college now offers women the opportunity to participate in nine different sports, including basketball, volleyball, and soccer. In a letter to women’s-advocacy groups a month before his election, Barack Obama wrote that Title IX had made “an enormous impact on women’s opportunities and participation in sports.” Two months into his term as president, he signed an executive order creating a new Council on Women and Girls “to ensure that American women and girls are treated fairly in all matters of public policy.”

In the view of one woman — my middle daughter, Dr. Juliette Landphair, who is dean of Westhampton College, the college for undergraduate women at the University of Richmond in Virginia — Title IX “has been hugely successful. So much so that the female varsity student-athletes at UR have no idea about it and just assume athletics has always been some sort of ‘right.’ It has made athletics a part of middle-class U.S. culture for girls as well as boys. Many other societies (e.g., Mexico) where, say, soccer is huge, do not have girls playing at a younger age the way the U.S. does.”

|

| Local soccer leagues and Little League softball are no longer the end of the athletic line for girls |

Girls who play sports are more confident, Juliette believes. “They are healthier (fewer occasions/desire to do drugs, drink). They find great friends and are exposed to opportunities they would never have had without sports.”

One “would be hard-pressed to find parents these days who do not want their girls playing some sort of sport,” Dean Landphair concludes.

I issued an invitation on Facebook to anyone who wanted to comment on the impact of Title IX. Linda Bjorkland replied from St. Paul, Minnesota: “Best thing that ever happened for young women….next to the vote perhaps.”

|

| It used to be an insult to say that someone played “like a girl.” These women could give all but the most muscular men a good game |

Susan Rice, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, wrote on a White House blog that “what I learned from my coaches and teammates” while playing high-school sports “extended well beyond the basketball court. . . . I’m often reminded that in basketball as in diplomacy, you have to know when to throw elbows and when to show finesse.”

Title IX detractors, mostly male, say the law has unleashed a wave of reverse discrimination, forcing institutions to eliminate men’s teams — often golf, wrestling, and track — to pay for all the new women’s sports. To use a sports cliché, Title IX has unevened the playing field, in some people’s view. A fellow with the online name “spikerritz,” for instance, wrote, in the parts that are tame enough to be quoted here, “Title IX is a joke. . . . It cost me personally a wrestling scholarship at the University of Colorado.”

All Title IX did, he continued, “was erase opportunities for men.”

Another man, using the name “DelcoDad,” stated, “Title IX is based on a false premise: that girls are as interested in competitive sports as boys. . . . At the high school level, Title IX often means that the girls’ soccer coach demands as much pay as the boys’ football coach, which is ludicrous on many levels. Count Title IX among the subjects about which one is not permitted to speak the truth.”

The intercollegiate athletic program at Howard University in Washington, D.C., is sometimes brought up as an example of this point of view. In 2007, its student body was two-thirds female, but women made up only 43 percent of the college’s athletes. The university responded by eliminating men’s wrestling and baseball and adding women’s bowling. The impact of Title IX’s proportionality standard “has been disastrous,” Wade Hughes, Howard’s former wrestling coach, wrote on “The Root” Web site, because “far more males than females are seeking to take part in athletics.”

In other words, schools must offer and fund sports programs for women beyond what they even want or need.

The U.S. Department of Education took a look at coaches’ pay at several universities in the year between July 2007 and June 2008. It found a great disparity. At private, Jesuit Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., for instance, coaches of male sports teams earned an average of $125,420 compared to $53,620 for coaches of female teams. The gap was roughly the same at public Syracuse University in New York State. But at Marquette University, another Roman Catholic college in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, coaches of male teams made about four times as much as female teams’ coaches. Virtually all men’s-sport coaches are male; about 52 percent of coaches of women’s teams are male as well.

As you might imagine, this gulf in the compensation of coaches prompted lively debate. Some who commented said that a coach is a coach — teaching, motivating, inspiring — with similar responsibilities and time required to do the job. Equality is equality, these proponents argued. Anything less is un-American. So there’s no excuse for paying the coaches of men’s programs like princes and the coaches of women’s programs like relative paupers.

Others countered that men’s sports are generally more visible, recruiting of athletes is critical and time-consuming if winning is to be achieved, competition for top-flight coaches is more acute, and attendance and fan interest are greater than they are for most women’s sports.

|

| It’s not hard to see why football is the Big Man on Campus when it comes to revenue. This is a North Carolina State Wolfpack crowd |

And this doesn’t even include the “elephant in the room”: the revenue that men’s sports — football and basketball in particular — rake in compared with mostly non-revenue-generating women’s sports. Therefore, goes the argument, coaches of men’s programs richly deserve their higher pay.

|

| Softball is a fast-rising intercollegiate sport. Women at large U.S. universities have competed for a national championship since 1982; men, playing baseball, since 1947 |

Whether one applauds Title IX or not, it has clearly changed the sports landscape. According to a longitudinal “Women in Intercollegiate Sport” study funded by Smith College and Brooklyn College, in 1970, two years before the law was enacted, the average number of women’s sports teams at each U.S. university was 2.5. By 2008, the number had jumped to 8.65 per school. And the study found that 2,755 new women’s-sports teams had been added nationwide just in the decade from 1998 to 2008. Another study, quoted in the Desert Beacon blog in Nevada, looked at the high-school scene. Whereas only 7 percent of high school athletes were female in 1972, the report showed, the figure had grown to 40 percent by this year.

You’ll recall that Title IX never actually mentions athletics, though it has become part of the American sports lexicon because of its effect on athletic competition and competitors. Title IX supporters are not resting on the laurels of girls’ increased participation in sports, or a vast escalation of funding for women’s sports and scholarships; they are beginning to look more closely at girls’ status in education as a whole. President Obama himself has called for “similar, striking advances for women in science and engineering.”

|

| This is graduation day the Virginia Tech University, renowned for its engineering and science program. The picture illustrates the gender imbalance in such fields |

But the idea that girls are somehow neglected or short-changed in academic subjects, even the traditionally male-dominated sciences, is preposterous, Title IX’s critics reply. John Hinderaker, a Minneapolis lawyer, and two other authors of the Power Line Weblog, scoff that “the comparison between female participation in college athletics and female participation in science and engineering is beyond specious.” Sports involve men’s and women’s teams, competing for resources, they say. “But men and women do not compete for slots on the same teams.” In graduate engineering, they continue, “the tracks are the same for both genders. Thus, men and women are in direct competition for the same slots. If the government wants to control that competition, it must override decisions about who the best-qualified competitors are. The analogy in the sports context would be requiring men’s basketball teams to include a certain number of women.”

Participation in college sports is an end in itself, Power Line argues. It is athletes’ reward for superb performance. Thus “a prima facie case can be made for ensuring that participation rates do not favor one gender.” But science is “very different,” the authors maintain. Promoting high-quality science and engineering, and a good livelihood for those who study in these fields, are the primary aim. If the government goes further and, Title IX style, tips the scale in favor of selecting women in the name of promoting equal participation, it will undermine American scientific excellence.”

Christina Hoff Sommers, an American philosopher and resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute — best known for her scathing critiques of feminists in books such as The War Against Boys — has noted that by 2002, women were already earning nearly 60 percent of all bachelor’s degrees and at least half of the Ph.D.s in the humanities, social sciences, life sciences and education, while men retained majorities in fields such as physics, computer science, and engineering. “Badly in need of an advocacy cause just as women were beginning to outnumber men on college campuses, well-funded academic women’s groups alerted their followers that American science education was ‘hostile’ to women,” Hoff Summers wrote. “Soon there were conferences, retreats, summits, a massive ‘Left Out, Left Behind’ letter-writing campaign, dozens of studies and a series of congressional hearings.”

Will a switch of Title IX emphasis to academics help American science as much as it helped women’s basketball? Hoff Summers asked. “Activist leaders of the Title IX campaign are untroubled by this question. Some seem to relish the idea of starkly disrupting what they regard as the excessively male and competitive culture of academic science.”

If you are confused by all this back and forth regarding equity in school sports and school itself, so are most Americans, even though we don’t seem to hesitate to offer our opinions when asked.

So what’s your vote?: Title IX is “the most important law in our culture” (Brennan) or “a bad joke” (Hinderaker and his Power Line co-bloggers).

Bed and Buzz

On the mercifully lighter side . . .

Another relatively obscure person with a fascinating life story has left us at age 92. John Houghtaling was never well known beyond his family and industry, but the product that he invented was an icon of American travel a generation ago.

John Houghtaling is the Magic Fingers man!

He was not a masseur, but his beds were, sort of, in motels all over America. Not sleazy “no tell motels,” either, but entirely respectable Mom and Pop establishments on the main drags of every decent-sized town. Surface travel in the 1960s and 1970s was grueling. Most highways were narrow and dotted with traffic lights and stop signs. Speed limits were modest, and you couldn’t go fast anyway because you were following one truck after another that was moseying down the pike. Then the roads ran right into towns, slowing you to a crawl.

|

| Here’s an old motel on historic U.S. Route 66 out West that might have featured the Magic Fingers experience. Might still today, in fact |

When you finally made it to the Mountain Aire Lodge or Sleep Rite Motel or Carl’s Cozy Cabins, you were bushed and really ready to relax. Many of these little places had no swimming pool, only three or four fuzzy channels on black-and-white TV, and window air-conditioning units that dripped and rattled and put out mere wisps of lukewarm air if they worked at all.

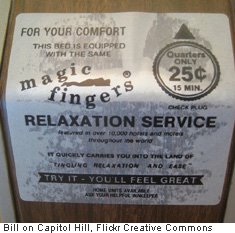

But if you were lucky, a Magic Fingers “relaxation service” — “featured in over 10,000 hotels and motels throughout the world” — was attached to your bed! In fact, there were 250,000 units in hostelries across the United States alone in Magic Fingers’ prime in the 1960s.

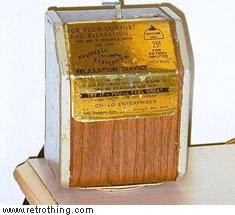

|

| This Magic Fingers box has seen its share of customers |

On your nightstand, you’d find a box about the size of an alarm clock, affixed with a sticker promising that the Magic Fingers would “quickly carry you into the world of relaxation and ease.”

“Try it,” the label urged. “You’ll like it.”

Millions did, by dropping in a quarter that got your entire mattress vibrating for 15 minutes. The idea was that the tingle would gently glide you into a comfy, satisfying sleep. Jimmy Buffett even sings about the sensation, in “This Hotel Room”:

Put in a quarter.

Turn out the light.

Magic Fingers makes you feel all right.

|

| I don’t recall a lot of “tingling relaxation and ease” during my few Magic Fingers moments |

My own experience with these units was that even if the slight jiggles would prompt me to nod off, I’d jolt awake when the unit shut off. This may have been the idea. With just one more quarter, and then another, you might finally settle into the embrace of Morpheus.

John Houghtaling — pronounced “HUFF-tuh-ling” — did not come up with the idea of a vibrating bed, but he simplified it. And the catchy name “Magic Fingers,” which he and his wife devised, didn’t hurt sales. As Houghtaling’s New York Times obituary noted, “The earliest vibrating beds predated the Industrial Revolution and were powered by household servants. Then came steam power, and after that, electricity. Mr. Houghtaling’s great innovation was to separate the motor from the bed.”

The problem with most earlier models, which were vibrating slabs built into mattresses, was that their manufacturers had to peddle the entire bed to motel owners — rumbling slabs and all. This was a hard sell for Mom and Pop proprietors, who had already invested in perfectly good beds and didn’t have $200 to $500 times 20 or 50 or 100 room “units” to spend on new-and-improved shaking beds.

|

| This is the prototype of the Magic Fingers motor unit, packed in what looks like little more than a tin can, then a snazzier cover |

In his basement in Glen Rock, a New Jersey suburb of New York City, Houghtaling tinkered with small motors. “I can’t tell you how many I went through,” he told American Heritage magazine in 2000. “I finally got to about 250th of a horsepower.” In the final prototype, weights were attached, slightly off-center, to a revolving disc that, in turn, was clamped to the motor. The offset weights caused the whole unit to vibrate, and the tricky part was determining exactly the right degree of oscillation. The completed fixture was placed in a can-like casing, then hung upside down and wedged into a space amid four different coils — not in a mattress but in the box spring below. A wire from the coin box set off the shaking.

John Houghtaling sold Magic Fingers to distributors — $2,500 for 80 units and three days of training.

The distributors went town to town, convincing motel owners to test and buy them. Although Houghtaling made a good living, he missed out on a fabulous one, since it was the dealers — not he — who collected the coins, splitting the proceeds, 80/20 with motel proprietors. One of Houghtaling’s sons, Paul, recalls meeting a distributor whose sales territory included six western states. “He’d drive the circuit and come back with $6,000 or $7,000 dollars in quarters” — literally a nice “chunk of change” in 1967 or 1968.

|

| Paul Houghtaling says his father was always tinkering with gadgets, had a cheerful outlook on life, and always preferred to work for himself rather than some big company |

The Houghtalings themselves serviced a few Magic Fingers units in the Miami, Florida, area. Paul remembers scooping up a few stray quarters that had fallen behind the bed or nightstand and been overlooked by motel housekeepers.

Overly torqued Magic Fingers beds became superb props for slapstick comedy. The gag beds produced teeth-jarring shudders that, no matter how frantically a pajama-clad “guest” clung to the headboard, tossed him or her onto the floor. In the 1987 movie “Planes, Trains & Automobiles,” a Magic Fingers unit vibrates so violently that a beer bottle explodes on the bed.

The dated technology and slightly frowzy connotation of a vibrating bed put an end to most of Magic Fingers’ motel trade, except in a few vintage motor-court-type establishments off the beaten path. As the Daily Finance Web site noted, “By the seventies, the scarred, fake-wood and brass boxes would seem to be a foundational part of the iconic sleazy motel room, as much a requirement as shag carpeting, cheap paneled walls, and unwashed comforters.” Daily Finance adds that the Best Western chain of independently owned motels specifically advised its proprietors not to offer Magic Fingers because they “cheapen the accommodations.”

Magic Fingers lost its customer base, too, because thieves kept breaking into the coin boxes or stealing them entirely. This problem was eventually addressed when Houghtaling devised a card containing a magnetic stripe that the customer would swipe through the pay box in lieu of depositing quarters. It was an early version of today’s debit card or key-entry card used to access hotel and motel rooms today. But the public’s fascination with trembling beds had waned.

Magic Fingers units are still sold on the Web, not to motels but to individuals. Often they’re baby boomers who are nostalgic, truly enjoy the tingle, or are disabled and perceive a bit of therapeutic relief from the unit’s rumblings. And any number of vibrating recliner chairs have borrowed the concept and are selling at a premium price.

Bloggers and their readers who heard about John Houghtaling’s death posted several reminiscences about the Magic Fingers device. One wrote that when, as a kid, he and his family would stop at a bargain-rate place, “usually called the ‘Dew Drop Inn’ or ‘Piney Top Motel,’” he and his brother would invest a quarter “out of our hard-earned allowance and put the quarter in the ‘Magic Fingers’ coin box. 9 times out of 10 it had no power left and would vibrate so slow that it was more annoying than relaxing.” Another online writer recalls being too embarrassed to try the unit. “If it worked, it might make such a racket that the entire motel would know. . . . It might be so old that if I inserted a quarter it would short out the device and sparks would fly and catch the bed on fire, causing the fire department to respond, leaving me to guiltily explain how my depraved actions resulted in the loss of the motel.”

|

| One little quarter would have satisfied a young man’s curiosity about Magic Fingers. Now he’ll have to go a ways to find an operating unit to try |

Now, he says, he regrets not investing that quarter. “I will spend the rest of my life wondering whether I could have enjoyed two nights being blissfully vibrated to la-la-land.”

Fifteen minutes at a time.

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Bushed. Exhausted. Apparently the word traces to the Dutch word for woods or wilderness, traipsing around in which is indeed tiring.

Embrace (or into the Arms) of Morpheus. Morpheus was the son of the Greek god of sleep. But it was a Roman, the poet Ovid, who gave him his own job, as the god of dreams. So it’s zzzz time when you fall into the arms of Morpheus.

Laurels. Awards or honors. Roman heroes were often crowned with stems of the laurel, or bay-leaf, bush. To “rest on one’s laurels” means that you are satisfied with your past achievements and not interested in working particularly hard to earn more.

Mosey. To amble, proceed at an extremely leisurely pace. The word may trace to an Old English word that refers to moving about in a dull, stupid way.

Prima Facie. From the Latin meaning “at first appearance” or examination. When one has a prima facie legal case, it means there’s apparent evidence of guilt that only strong refuting testimony could disprove.