Almost 13 years ago on a Sunday, I walked into a surreal urban setting that reminded me of one of those science-fiction movie scenes in which everything looks normal but there’s not a human being in sight.

Once a stable, this became the engineering unit’s headquarters building at the facility I’m about to describe. (Chris Hatch, U.S. Navy Naval Ship Systems Engineering Station)

There were manicured lawns and old, beautifully kept red-brick buildings, something like a college campus without the students. Or the professors. Or anyone at all. You could still see machinery inside industrial buildings through windows that were perfectly intact. It was as if the workers had switched off their machines, gone home, and never come back. Or been vaporized.

In a word: spooky!

And it got eerier, because straight ahead of me appeared about 30 giant U.S. Navy warships in battle gray — including a huge battleship and two even larger aircraft carriers, rising and falling ever so slightly on the Delaware River tide. Once again, without a person to be seen on them or ashore.

This all took place in Philadelphia, a great industrial city that once made everything from saws to locomotives to many of those ships.

This is Carol’s shot of what I saw in the Delaware River when I visited the Naval Shipyard. Check out what’s in the distance. (Carol M. Highsmith)

The locale was what was then called the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, which, just eight or nine years earlier, had been Philadelphia’s largest manufacturer. More than 40,000 people at a time once worked there, building mighty ships.

So you can imagine that in 1991, when the government ordered several American military bases closed to save money — and this shipyard was announced as one to be severely curtailed within four years — it was a shocking and sad time for the nation’s fifth-largest city.

My surreal visit occurred after the place had been all but cleared out, with the weekends just about unstaffed.

In a bit, I’ll tell you what happened then, but first some essential background.

Pennsylvania Colony was founded in 1682 by Quakers, including William Penn, for whom it was named. Though pacifists, these folks did not miss the military significance of the location of the colony’s principal city, Philadelphia, along the deep but fresh water of the Delaware River, upstream from the ocean and away from easy attack by foreign powers.

In the mid-1700s, colonial leader — and later revolutionary conspirator — Benjamin Franklin obtained financing for two gun batteries on the river in the borough of Southwark in what is now South Philadelphia. One of them would later become the site of Philly’s first Navy Yard. Private shipbuilders set up shop on the waterfront as well, turning out huge merchant ships.

James Fuller Queen’s painting shows quite a scene on the Delaware River. Imagine how much livelier summertime would have been. (Library of Congress)

As the American Revolution was coming to a boil in 1775, Franklin and others found the funding to convert several merchant ships into the rebellious colonists’ first warships. The British seized Philadelphia and all its shipyards, but only for about a year before being driven from town. Once the colonists’ victory was achieved and a nation was formed following the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the new United States moved military shipbuilding to Boston.

Philadelphia continued to build big merchant ships, however, as well as a class of government vessels called “revenue cutters” used to collect customs duties. But after Barbary pirates attacked U.S. merchant and naval vessels off the coast of Algeria as the 19th Century dawned, demands for a stronger Navy grew. And they intensified with the coming of civil war and the need for fresh water on which to build and store the new iron-hulled warships — rusting being a serious problem in salt water.

The Union’s ironclad “Monitor,” right, engages the southern Confederacy’s “Virginia” in Julian Oliver Davidson’s memorable illustration. (New York Public Library)

Many of the Union Navy’s fabled and frightening steam-powered, ironclad warships were off League Island, to which the Navy gradually moved its entire Philadelphia shipbuilding operations. Lacking much space to expand amid the crowded private shipyards along the Delaware, the Navy shifted operations to this island, which was actually little more than a soggy wetland with a few high spots at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. Once it took full possession after the Civil War, the Navy dumped dirt on the island to build it up and made it its fulltime base of operations.

It included a “reserve basin” for mothballed ships — a concept I’ll delve into shortly — in the island’s back channel as the temporary, and sometimes next-to-last, resting place of warships from previous conflicts.

Before and during World War I, the yard launched several troop ships, including some made from captured and refitted German ships and U.S. vessels that had been bobbing in the reserve basin.

This 1920s League Island postcard view was made from a colorized black-and-white photo. (Library of Congress)

Here’s that behemoth of a crane. It looks big enough to pick up a whole ship. (U.S. Naval History Center)

Some of the Navy’s first women yeomen served as clerks and telephone operators at the yard during that conflict, as did almost 900 other women at an aircraft assembly plant elsewhere on League Island. Over the next few years, what for a time was the world’s largest construction crane — a T-shaped “hammerhead” monster 76 meters (250 feet) tall, capable of lifting 250 tons — was erected in stages. It proceeded to tear apart and help assemble hundreds of ships. It’s still working and is much loved by those who toil at the yard, because of a tinkly series of bells that sound when the crane is rolling down its railroad tracks. Folks at the yard call it “the ice-cream truck.”

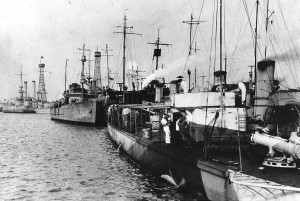

Looks like there might be an active ship among the mothballed ones at League Island immediately following World War I. (U.S. Naval History Center)

Following the Great War, part of the channel between League Island the mainland was filled in to create an airfield as aircraft production increased, and a number of warships were mothballed as part of a global arms-limitation agreement. All that would change, however, in the run-up to World War II, for which two of the world’s largest drydocks at the Navy Yard turned out 48 new and 600 or so refurbished ships. Keel layings and ship launches became huge civic occasions. Some of the celebrants came from the tens of thousands of workers at the Navy’s ship and airplane facilities.

Coming out of World War II, several ships that had been borrowed from private shippers were “de-outfitted” and returned to those companies. And as Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union mounted, many submarines were re-equipped with top-secret snorkel and sonar devices. Other ships were rebuilt for service in the Vietnam War, but questions about the yard’s usefulness were beginning to be heard as the Navy centralized commands at a bigger base in Norfolk, Virginia. It didn’t help the old Philly yard’s profile when 800 pipefitters, welders, and others were sickened by asbestos poisoning, leading to expensive abatement operations involving tons of asbestos-related debris.

An exquisite birds’-eye-view of the “reserve basin,” taken in 1938. (U.S. Naval History Center)

The Yard kept cranking for a time, though, thanks to the Navy’s decision to extend the normal service life of six giant aircraft carriers. Work on them took 16 years. Then, in 1991, came the dreaded BRAC hammer: the military-wide Base Realignment and Closure program, aimed at cutting the nation’s defense spending. Save for its foundry and propeller shop, mothballed fleet maintenance, and engineering research functions, the Navy Yard was told it would be no more.

One September day in 1995, the John F. Kennedy — the Navy’s last conventionally powered aircraft carrier and the last great ship built at the Philadelphia yard — put to sea. As the ship pulled away, she turned broadside, perpendicular to the pier, and fired off an 11-gun salute to the shipyard, an unprecedented gesture there.

At that point, as Bob Gorgone, who was director of civilian operations at the yard then, told me, “All the workers turned to each other, started shaking hands, said, ‘Have a nice life’ to each other, and went home.”

These are some old Philadelphia Naval Shipyard warehouses a few years after the facility closed. (getoutphilly.org)

Rear Admiral Louise Wilmot, the first woman to command any U.S. Navy base and the first to shut one down, presided over the official closing of the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard a year later, on Sept. 27, 1996. As had been the custom for 120 years, an entry was recorded in the facility’s station log:

Shipyard commander arrived, observed morning colors, commenced closure ceremony; shipyard commander orders the watch secured and Philadelphia Naval Shipyard closed; secured the watch; Philadelphia Naval Shipyard closed; no later entries this log.

The shipyard had been extremely productive, but it had one fatal disadvantage. By 1990 U.S. submarines and many aircraft carriers had gone nuclear, but the City of Philadelphia wanted no part of large-scale work involving nuclear materials within its borders.

Left behind when the base closed were several ships — part of the mothballed “inactive fleet.”

My guess is that every one of these decommissioned destroyers, shown in 1919, is now a fish habitat or a museum, if there’s anything left of them at all. (U.S. Naval History Center)

Some mothballed ships are destined for scuttling as manmade reefs, or use as target practice for crews of newer ships. Needless to say, neither prospect pleases those who once served on these rustbuckets.

Other mothballed ships end up in a nautical junkyard in Brownsville, Texas, to be ripped apart for components and scrap metal. One fellow at Philadelphia’s Navy Yard told me, in fact, that if I shave with a Gillette razor, I might well have scraped my stubble with a piece of metal salvaged from a Navy vessel that the company purchased. Recycling on a grand scale!

But other ships at the Navy’s “inactive maintenance facility” come to life again as floating museums or are sold to other governments and remain in service. Some stay right there in the reserve basin — sealed, lightly air-conditioned, and electrically charged to deter rusting — in case they’re needed to fight a new, large-scale war. Two mothballed ships in Philadelphia are giant aircraft carriers, including the aforementioned U.S.S. John F. Kennedy. Several cities have expressed interest in it as a museum. From what I’m hearing, the other carrier, the U.S.S. Forrestal, will likely be heading to Davy Jones’s locker for reef duty.

When a military base closes, the Navy, in this case, must first offer the property to the other armed services: the Army, Marines, and Air Force. They all said thanks but no thanks. So did other federal-government agencies next in line.

But before the base and its unclassified equipment could be auctioned off to private investors, the local community gets the last crack.

Bingo! Philadelphia said yes, it would love the property as an industrial and research park —a gigantic 445-hectare parcel that’s bigger than downtown Philly.

Urban Outfitters did some amazing rehabbing of old structures at the Navy Yard. Here are a couple of them. (Pennsylvania Industrial Development Corporation)

No massive clean-up or demolition was needed. The site at the foot of the city’s most famous street was well-maintained, fenced in, tree-lined, and ideally suited just five minutes from the Philadelphia airport and right next to lines of three freight railroads. And it was secure. Guards at the main gate at the foot of Broad Street weren’t going anywhere, because the Navy still had about 2,500 people at work on about one-eighth of the property. They just switched from armed seamen to private security guards.

For quite a while on weekends, however, the Navy Yard was that veritable ghost town that I described.

But as I walked it those many years ago, I knew that it had the makings of something grand. Already in my hometown of Cleveland, the once-deserted wasteland of factories, steel mills, and breweries called The Flats became the hottest destination in town, filled with new and renovated buildings, white-collar businesses, and trendy restaurants and bars.

Philadelphia offered a much cleaner and safer site, and it brought in a public-private entity called PIDC — the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation, founded in 1958 — to act as the recruiter of private businesses, landlord of some of the old buildings rented by new tenants, and overseer of the lion’s share of the yard not in the Navy’s hands.

In the distance beyond Aker’s shipbuilding facilities, is a good view of the Philadelphia Skyline. (Aker Philadelphia Shipyard)

One of its first takers was Kvaerner, Europe’s largest shipbuilder. It installed millions of dollars’ worth of modern facilities but kept the enormous drydock that the Navy had used to build aircraft carriers. In 1995, after creating four humongous container ships, Kvaener sold the operation to Aker American Shipping, which split off what’s now called Aker Philadelphia Shipyard as a subsidiary that makes tanker ships for Aker’s operational division. Ten tankers to date, with one in drydock right now.

Tasty Baking’s gleaming facility at Philadelphia’s Navy Yard is quite a bakery! I hope all the “green” technology hasn’t squelched the wonderful smells. (Pennsylvania Industrial Development Corporation)

And there’s another product, quite different from monster ships, leaving the loading platforms at today’s Navy Yard. It’s Butterscotch Krimpets, not to mention chocolate-covered donuts and yummy fruit pies. That’s because a revered Philadelphia institution had closed elsewhere in town. The Tasty Baking Company began baking the small, butterscotch-frosted cakes in 1918 and pioneered the idea of individually packaged, lunchbox-ready snack pies in the 1930s. After shuttering its 1922-vintage, six-story North Philadelphia plant, Tasty Baking moved its operations to a 32,000-m2, one-floor, “green” bakery at the Navy Yard. This plant may have energy-efficient ovens, but it can really crank out the crumbly snacks: 4 million Tastykake items each day.

Not far away at the revived yard is another showplace property. Urban Outfitters, the trendy “lifestyle designer” and clothing manufacturer, also left older spaces in downtown Philly for a new corporate campus at the Navy Yard. The company occupied and revived several of the century-old warehouses and factory buildings that give the yard its quaint, Victorian flavor.

The naval personnel who remain at the Navy Yard aren’t just watching over old, abandoned ships.

Smelters are still firing at a bustling, secretive Navy foundry. What’s so secret? The molten metal is fashioned into submarine propellers that run as close to silently as any on earth. Deep within the sea, silent means safe. And secret.

And a Navy outfit called the Ship Systems Engineering Station stayed put as well. It involves about 1,600 engineers, scientists, and technicians who — for 100 years precisely since the time when the unit was busy converting the Navy’s fleet from coal to oil power — have designed propulsion systems and sophisticated nautical gear. “Green” technology, especially, these days, including hybrid drive systems and alternative fuels. Gas turbine engines and electric auxiliary propulsion systems designed in Philly, for instance, helped the U.S.S. Makin Island — an assault ship that can deploy U.S. Marine helicopter and land forces — save $1.6 million in fuel costs on a single voyage around South America’s Cape Horn.

One can only imagine the total fuel bill for that trip, even with the savings.

All in all, Philadelphia’s Navy Yard waterfront development includes more than 511,000 m2 of newly occupied business buildings, the Navy’s foundry and engineering facilities, a number of sycamore-lined “pocket parks” for strolling, and — for 8,000 employees and untold visitors alike — old, gray ships, rocking gently as a backdrop.

You’re welcome to visit — on weekdays. But gates are down and security is in place after sunset and on weekends. If you want to check out the mothballed ships then, you’ll have to peer across the Delaware from New Jersey.

The stylish gateway sign needs a mermaid or something. (Pennsylvania Industrial Development Corporation)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Davy Jones’s locker. Another name, or euphemism, for the sea bottom, the graveyard of dead sailors and sunken ships. In early sea lore, Davy Jones was the devil, or the evil spirit of the sea.

Veritable. Close to the real thing. Something that is a “veritable gold mine,” for instance, isn’t a mine, but it’s extremely valuable.

4 responses to “Out of Mothballs”

The virtual tourism is appreciated.

I really enjoyed this article. As a white hat (enlisted sailor) I worked in the building first shown in this article and identified as a former stable. The 4nd PAMI (Personel Accounting Machine Installation) was housed here where I was stationed in 1955 and 1956. Thanks for the update and info on the Phila Naval Yard.

LCDR Keith Meakins, SC, USNR, RET

I noticed a website yesteday which seemed a lot similar to this, are everyone sure somebody is not copying this web-site?

Send me the url of the “similar Web site” and I’ll see whether it’s a copy. They say “anything goes” in the blogosphere, but I don’t believe it should include plagiarism.