The image of New Englanders — the folks who live in America’s northeast corner — is one of people who don’t talk a lot. Stoic, quiet types who keep their thoughts to themselves. You’re lucky if you can get an old-time New Englander to say “ay-yup” or “nope.”

Talking's not all that goes on at Warren's town meeting. There's a lot of listening, too. (Courtesy, The Valley Reporter)

But one day a year, the citizens of villages, towns, and mid-sized cities gather in town halls and school auditoriums to talk-talk-talk — sometimes all morning, all afternoon, even late into the night. It’s as if reticent New Englanders save up all their thoughts — about all sorts of things — and get them off their chests on a single day.

Sometimes called “the purest and most democratic form of participatory government,” town meetings are literally open to anyone and everyone in town. It’s a tradition that dates to colonial times more than 235 years ago. As Jeremy Perkins notes on the suite101.com Web site:

The first recorded gathering of voters in America took place in Dorchester, [Massachusetts] in 1633. According to the Dorchester Athenaeum online . . . . the gist of this historic first was that the townsmen, by vote, agreed to meet at regular intervals to see to the “good and well ordering of the affayres of the Plantation.” Soon after, the greater Boston area had begun adopting the process.

And it spread across New England from there.

Here's an idea of how tranquil Warren looks in this quintessential New England scene. (The Valley Reporter)

The traditional date of the town meeting on the first Tuesday of March was chosen because the region’s fierce winter usually moderates a bit by then, and farmers in the area who didn’t see each other often could come because the crops weren’t yet in the field. But bigger communities now often schedule town meetings for an evening or a Saturday, knowing that not everyone can get a weekday away.

Residents of towns such as Warren, Vermont, near the big Sugarbush ski resort in the Green Mountains, get the following notice in the mail:

WARNING FOR TOWN MEETING. RESIDENTS WHO ARE LEGAL VOTERS ARE HEREBY NOTIFIED AND WARNED TO MEET.

Not invited . . . warned! These folks take town meetings seriously. Warren has no mayor; it’s led by five “select board” members — they used to be called “selectmen” until a woman got elected. They and other town officials must get up, explain their plans, and defend their record before the whole town — not as Republicans or Democrats but as neighbors charged with running the place.

On March 1 moderator Robert Messner, a retired engineer, will bring forth agenda items, including the annual budget. This year, for example, Warren — which Vermonters call one of the “gold towns” because it’s one of the state’s wealthier communities — must find $375,000 with which to repave the road to the ski resort.

Attendees don’t walk into the meeting cold. Well, it can be mighty frosty outside. What I mean is that in advance they’re given a thick “town report” summarizing issues sure to be brought to a vote. Of course that doesn’t prevent some citizens from ignoring the prep work and sounding off anyway.

Presumably Mom has already looked through the town booklet, and the little one is just catching up. (John Williams, The Valley Reporter)

That’s why the moderator’s job is tricky and prestigious. The day of the meeting, the following year’s moderator is elected by secret ballot, cast elsewhere in the meeting hall — the elementary school in Warren’s case.

Messner runs the meeting according to a modified version of Robert’s Rules of Order. When open-ended “other business” is announced, the fun begins. People can bring up anything they like — and do. Out the window goes the “laconic New Englander” stereotype.

Just as March is sap-rising time in Vermont’s maple trees, tempers sometimes elevate as well. Messner says he’s rarely surprised about anything that’s brought up, since — in tried-and-true small-town fashion — most everybody already knows everybody else’s business and opinions.

Warren resident Dean Auschlander makes a point at the 2009 Warren town meeting. (John Williams, The Valley Reporter)

About 300 or so folk typically show up at Warren’s town meeting — though the number can get larger if something controversial is on the docket. Years ago, for instance, the hall was packed when many feisty Vermonters were determined to speak out against the nation’s involvement in the war in Iraq, half a world away.

There have also been years in which a Vermont secessionist movement calling for the provocative but unlikely idea — though one that polls show as many as 15 percent of Vermonters endorsing — of withdrawing from the American Union. Likewise, many young adults who moved to Vermont because of its activist environmentalist tradition get worked up about one “green” thing or another and want to talk about it at the town meeting.

Everyone gets a chance to speak — up to a point. Bob Messner has what he calls “cutoff mechanisms,” but they’re not employed just to cool off hotheads and windbags. Everyone has an eye on the clock for two other reasons:

It would be unfair, but not entirely untrue, to say that the potluck lunch is more of a draw to some than the town's business. (John Williams, The Valley Reporter)

The school board, which has a larger budget than the town, meets in the afternoon — though that hasn’t always kept the town meeting from running long when sparks are flying. More often it’s the scents from the kitchen — emanating from home-cooked casserole dishes, pies, cakes, and other treats that people bring to the closing “pot-luck” lunch — that put a zipper on proceedings.

“When my wife was asked to make a warm dish for the town meeting, we felt we’d arrived,” Frank Partsch, the owner of one of Warren’s bed-and-breakfast inns once told me, a year after he moved to town. “You may not a ‘real Vermonter’ yet in everyone’s eyes, but you’re OK.”

Partch called town meetings “Vermont’s dinner theater.”

By the way, if you’re intrigued by the town-meeting process, you can follow coverage of Warren’s event in the area newspaper, The Valley Reporter, which, as you may have noticed, graciously allowed me to use some of its photos from previous years in this posting.

I didn't want us to leave New England without showing you another iconic shot of Vermont. (Carol M. Highsmith)

****

The Devil Made Him Do It

The owner of the Washington Redskins professional football team, Daniel Snyder, is not a particularly popular fellow.

Dan Snyder and his top coaches have been known to use Snyder's jet to fly in highly recruited prospects. (drewski2121, Flickr Creative Commons)

He’s young (45), rich, and successful — at least in his other enterprises. He sold his advertising and marketing company to a French firm for stock valued at $2 billion and has since purchased radio stations, a chain of theme parks, and a television production company owned by legendary TV personality Dick Clark.

For that, he’s admired and envied. For his stewardship of the football team, however, he’s widely disliked, even hated.

In that realm Snyder has raised ticket, food and beer, and parking prices at his team’s games — played at the second-largest stadium in the National Football League — and, according to his many media critics, heartlessly fired several long-term employees of the team. But worst of all in the eyes of those who hate him, his once-dominant football team has posted losing records in all but three seasons since Snyder bought the team in 1999.

This hot-air version of a Redskins' helmet appears to have collapsed. Critics would say the image mirrors the team's recent seasons. (dukiekirsten3, Flickr Creative Commons)

Against this backdrop, on November 19th a free, alternative newspaper called the Washington City Paper published a scathing article about him. Called “The Cranky Redskins Fan’s Guide to Dan Snyder,” it recapped his football team’s many years of futility and recounted some of Snyder’s business dealings in caustic terms.

To top it off, the article was accompanied by a photograph of Snyder on which an illustrator — imitating the style of a graffiti artist who might have come across the billionaire businessman’s image — scrawled a crude mustache, goatee, and devil’s horns.

Snyder was none too pleased. According to his spokespeople, he demanded an apology from the newspaper and a retraction of material in the story that Synder characterized as “lies.”

When he got neither, he filed a lawsuit against the newspaper and its parent companies on February 3rd, accusing them of “lies, half-truths, innuendo, and anti-Semitic imagery to smear, malign, defame, and slander” him and his wife, Tanya.

This, in turn, prompted a media backlash that may have surprised even Snyder, who is certainly used to criticism. The fusillade was aimed at Snyder’s sensitivity about the doctored photo, in particular.

The lawsuit asserts that “in its cover art, the Washington City Paper depicted the Jewish Mr. Snyder in a blatantly anti-Semitic way, complete with horns [and] bushy eyebrows.” It was, the suit asserts, “precisely the type of imagery used historically, including in Nazi Germany, to dehumanize and vilify the Jewish people and associate them with a litany of libels over the last 2,000 years.”

No, most columnists who saw the image and read Snyder’s complaint responded, it looked exactly like the work of a street tagger who didn’t care for the fellow in the picture.

But that wasn’t the bulk of the blowback to Snyder’s lawsuit.

How dare the owner who had defended the “Redskins” nickname over and over again as not the least bit insensitive to American Indians dredge up the “Nazi card” and cry anti-Semitism, they said.

The Redskins are one of two NFL teams with marching bands. Those in the other one don't wear Indian headdresses. (littlerottenrobin, Flickr Creative Commons)

“Dan, every major Native American organization in the country supports the lawsuits that have been filed against your team seeking revocation of that racist trademark,” wrote Courtland Milloy in the Washington Post. “Thousands of public schools and colleges throughout the country have stopped using Native American images as sports mascots.”

Milloy is right about that. The Stanford University “Indians” are now the “Cardinal” — the color, not the bird. St. John’s “Redmen” are the “Red Storm.” The Miami (Ohio) Redskins became “Red Hawks,” and so on.

But the Washington pro football team is still the Redskins. “The name is not meant to be offensive,” Dan Snyder reiterated to a local radio station. “To compare that to [the illustration of him] is silly.”

But Ken Stern, director of anti-Semitism and extremism for the American Jewish Committee, begged to differ. He told Milloy, “Say, instead of Washington Redskins, we had a football team called the New York Jews that had a logo with an image of an Orthodox Jew [the Redskins’ logo depicts an Indian warrior wearing two feathers] and used paraphernalia that trivialized Jewish religious symbols. I’m sure many would find that unacceptable.”

And John Feinstein, a prominent, nationally syndicated sports columnist who is Jewish, lashed out at Snyder’s use of what Feinstein called “the Jew card.”

He and his minions found a Rabbi at The Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles who was willing to call the cartoon anti-semitic. Oh please. A newspaper ran a cartoon depicting [Duke University basketball coach] Mike Krzyzewski as the devil during last year’s Final Four [tournament]. Was it in poor taste? Sure. But was it anti-Polish? Of course not. No one is anti-semitic here. They are anti-Dan Snyder. Period.

Two days after Snyder filed suit, David Friedman, director of the Anti-Defamation League’s Washington region, told the Washington Jewish Week newspaper and Web site that even though the City Paper article never identifies Snyder as a Jew, when he took offense to the “devil” caricature the paper should have apologized. But Friedman said filing suit was taking his pique too far. The Redskins’ owner is “being demonized because people are angry about his ownership, not because he’s a Jew,” he said.

Separately, Washington Jewish Week, which has covered the area’s Jewish community for 80 years, reprinted the “Snyder as Devil” photo and reported the results of a survey of its online audience on the matter. Of those who responded over three days, 94 percent said the Washington City Paper article was not anti-Semitic.

Several stories pointed out that defamation or libel lawsuits brought by public figures are historically difficult to win, since criticism of them is accepted as part of American free speech.

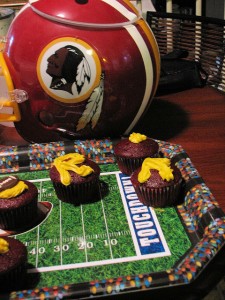

This Redskins helmet, with its Tuscan-red-colored warrior logo, is a centerpiece of this creative and tasty-looking display. (littlerottenrobin, Flickr Creative Commons)

In a letter to the City Paper’s parent company, Redskins’ general counsel David Donovan made it clear that his wealthy client had plenty of wherewithal to carry the lawsuit forward. He wrote, “Indeed, the cost of litigation would presumably quickly outstrip the asset value of the Washington City Paper.”

For sure, defending such a suit is costly. But as columnists across the country quickly pointed out, the Washington City Paper, a theretofore obscure local giveaway sheet, was reaping unimaginably valuable publicity as a result of the suit, as were the individuals and groups who oppose “Indian” nicknames.

Many writers who have exhibited no particular grudge or venom against Daniel Snyder have written that while the football team owner has every right to redress perceived wrongs to his reputation, the lawsuit is a mistake, since it reinforces the owner’s reputation as a bully.

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Fusillade. A rapid-fire, overwhelming volley of shots.

Laconic. Terse, succinct. People of “few words” are said to be laconic.

Windbag. A speaker who talks on and on, filling the air with overblown statements and promises.