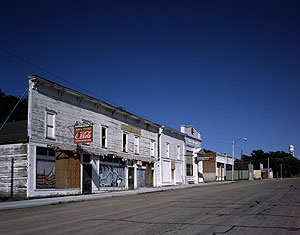

These are gloomy days in much of rural America. One national newspaper described what it called a giant “rural ghetto.” Another’s story, titled “America’s Failed Frontier,” concluded that the farm belt is steadily dying. When we think about ghettos, we picture old, dilapidated inner-city communities. But poverty and decay are rife in the country as well.

By that I mean the country country, where cows and chickens and coyotes, as well as people, live the best they can.

Boom-and-bust cycles are nothing new to rural America, of course. In 1987 two New York academics, Deborah and Frank Popper, found the economic prospects on the Great Plains so grim that they advanced a radical solution that has become a metaphor for a region in steady decline:

Shut the whole place down, the Poppers advocated, and return it to a “buffalo commons,” where tourists could see bison once again and hike the tallgrass prairie.

That was exaggeration for effect. At least I hope so.

But this year, Oklahomans and Texans have lived through the worst drought since the Dust Bowl days of the 1930s. And there’s been a sharp drop in commercial activity in nearly every county — and declining population in several — all the way up to North Dakota at the Canadian border.

In fact, America’s poorest county is nowhere near a big city. Ironically — the Poppers should read this — it’s Buffalo County, South Dakota. Four other counties with the nation’s 20 lowest income levels are in South Dakota, too, and the remaining 15 are in rural parts of Texas, North Dakota, Alaska, Mississippi, Kentucky, Louisiana, and New Mexico.

In hard-pressed rural backwaters, the triple whammy of a shaky national economy, ever-fluctuating farm prices, and continued takeovers by corporate farming enterprises has put thousands of small-scale family farmers out of business.

At the same time, millions of rural, often low-skill, industrial jobs, especially in the South, have fallen prey to the dismal trends in U.S. manufacturing, including downsizing, plant modernization, and the export of jobs overseas. In many Midwest states, Hispanic workers have moved in to take low-paying jobs in mills and processing plants, changing not only employment demographics but also the entire cultural dynamic of what was once a homogeneous — non-Hispanic white — population.

Rural Iowa alone has 12 times as many Hispanic residents as it had a decade earlier.

In that same period, almost one-third of rural Great Plains counties lost 10 percent or more of their people. Meantime, 103 plains counties that include decent-sized cities grew by 12.7 percent.

So what is now America’s age-old flight from farms to big towns has not abated.

It’s easy to understand why. According the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey Institute, which conducts policy research on vulnerable children and families, 46 per cent of America’s rural children live in poverty.

Good news in the country country is hard to find.

I’m a city fella, born and raised and still dwelling. But a few years ago, on an extended visit to Kansas, I got a sobering look at the challenges that rural Americans face.

That's Steve Bacchus in the center, with Chris and Karen Campbell of Leavenworth County, Kansas, on a lobbying trip to Washington. (Kansas Farm Bureau)

Steve Bacchus was, and remains, the farm bureau president there. “There’s a tremendous amount of heartache,” he told me.

My phone rings literally daily — not just from farmers who are losing their land, being forced off the land because they can’t get the money to keep going. But I get phone calls from businesses. And they’re asking, how are they going to stay in business? How do we sell enough cars to stay here, or the insurance companies, how do they sell enough policies to stay on Main Street? There is real concern out in the country now about not just losing the American farm in rural Kansas, but losing rural communities, entire towns simply dying and going away.

Things fluctuate out in the country country from month to month and year to year, depending on crop prices, droughts, and storms. But most economic trend lines keep spiking downward.

At the state’s principal agricultural research center, Kansas State University in Manhattan, economist David Darling has tracked it.

“As they say in Chinese proverbs, ‘May you live in interesting times,’” he said to me. “Well, there are a lot of people in Kansas who are hurting, and there’s no question about it. The question is, what are we going to do about it?”

Darling told me he is in what he calls the “hope business.” He tries to help small towns take advantage of what assets they have. Dr. Darling says survival in hard times calls for a core of optimists willing to develop a vision for their town, then an economic action plan. But more often than not instead, he says, skepticism greets him.

There’s a lot of hurt in the countryside. They really do have to ask themselves, “How are we doing business? And should we do business a new way?” I was in Ellsworth the other day, and they actually admitted to me that they do not have a coherent plan to move forward. Places that are hurting the most often are their own worst enemy.

The best hope for many rural counties, Darling believes, is a regional approach in which economically sound communities like Salina and Hays become employment, education, and medical hubs, and surrounding counties offer recreation, tourism and agricultural support.

Regionalism is a marvelous idea, agrees Steven Baccus at the state farm bureau, but many Kansans want no part of it. When he speaks of “Minneapolis,” he means a small town, population 1,950, in the center of the state — not the big city up in Minnesota:

There’s a four-lane interstate highway between Minneapolis and Salina. I can leave Minneapolis, and 20 minutes later I’m anywhere I want in Salina. A lot of people in Minneapolis go to Salina to shop. A lot of people live in Minneapolis — it’s a bedroom community — and work in Salina. It seems to me like the City of Salina and Saline County have a responsibility to those outlying areas to keep them strong, keep them viable, keep those people happy, keep ’em healthy with good medical services and everything of that nature.

As to how our people would respond to it: the first response to it would be negative, because they would think that Salina is trying to put its tentacles in and tell them how to run their community.

Like it or not, though, folks on the farm and in small towns are having to accept regionalization — and corporatization — of health care, schools, shopping, and services that used to be a part of every town.

Even modestly sized Salina has a lot more culture to offer than do the towns in the countryside. This is the Steifel Theatre for the Performing Arts. (Salina Convention and Visitors Bureau)

Terry Kastens, who teaches farm management at K-State, said that if his colleague, David Darling, is in the “hope business,” he’s in the “reality business.” Ever-growing, technologically advanced farm operations are going to continue to supplant family farms, he says.

But so what? They bring jobs for farmers as employees. “And a lot of times, those employees are happier than they’ve ever been in their lives.”

They’re no longer starving to death. They still get to do all the things that they enjoy doing as a farmer — operating a tractor and so forth. Even though farms are getting bigger, we’re not necessarily getting rid of people totally. As farms get bigger, they’re going to have to hire people.

And then Terry Kastens said something stark and shocking:

Some rural poverty is by choice.

My own son, who has a master’s degree in geography, and his wife, who does as well, moved back to the farm specifically because they wanted their children to have the same life experiences that they had, growing up in a small, rural community in northwest Kansas. They made that choice being conscious that they probably won’t have the standard of living that they would have had had they stayed in the city. The standard of living is about more than the amount of money you take in.

Things haven't regressed to sod-house days, at least not yet. Yes, that's a cow on the roof. (Library of Congress)

Many articles about the decline of rural America — especially the “brain drain” of young people who leave for Denver or Chicago or Kansas City — grasp at the Internet straw as a possible salvation. People can work at home in the tranquil countryside, the reasoning goes, and build businesses with the same information streams that sophisticates in metro areas have available.

But how can a town like Syracuse, Kansas — 400 kilometers from even a medium-sized city — compete with the nightlife, sports, and cultural options of a Kansas City?

It can’t, and as a result, many small towns across the American Midwest are withering. Steadily losing people and Main Street businesses, they await the coup de grace: the closing of their schools.

I visited such a town.

Delphos, Kansas, has never been more than a dot on a map, up the road from Salina, which isn’t all that big itself. Just 431 people were counted in Delphos and the surrounding countryside in the 2010 census.

In the past 10 years, a nursing home — the town’s largest business besides the grain co-operative — closed for lack of residents. At the time, Greg Berndt and his wife, Carrie, owned Delphos’s only remaining grocery store in a century-old building with tin ceilings, a front screen door that squeaked, and a bell that jingled each time a customer walked in.

“When we opened the store, we had a lot of older residents, up in their 70s and 80s,” Greg told me. “But the older people keep dying off, and when you know all your customers, each one of them, it seems like there’s more passing away than new ones coming in.”

At the same time, young couples and high-school graduates were leaving Delphos — and hundreds of other heartland small towns — in search of better jobs and a livelier social life.

And with them went young children, cutting the enrollment in elementary and middle schools to the point that many have been forced to close.

That a town’s death knell, as I said. Its little gasoline station — usually the only one — relies on income from fuel pumped into school buses. Teachers and students — and parents who pick up their kids after school — make purchases that keep country tores afloat. Post offices close once the population slips below a tipping point. And the “school spirit” that goes along with sports and other activities flags when there is no school, and kids are riding buses to a larger town.

Still, with all of its stresses and shortcomings, rural America has its comforts — psychological and spiritual if not material.

“Runnin’ the store here, if somebody’s sick, they need groceries delivered to ’em, we go into their house, leave the groceries — put ‘em away for ’em, even,” Greg Berndt in Delphos told me. “You can’t find that ever’where.”

Stephen Baccus, the Kansas Farm Bureau president, grew up in Minneapolis — the little one in Kansas — and sent his kids to school in Delphos. “The school system’s enrollment and budget have declined,” he stated the obvious. “You have to make some changes if you’re going to stay a viable, economically sound school system. Delphos is very much aware that [if] you lose your school, that is probably one of the last steps before your community implodes on itself.”

And lose it Delphos did. Its kids now bus to two other towns.

And it lost the Berndts’ general store, too. Greg is now farming in the area.

“Look, if we fail, I can always hold my head up high and say, ‘We tried,’” he told me when I visited years ago. “We’re just bull-headed.”

But the little bell on the squeaky door didn’t tinkle often enough to keep the store open.

You can buy chips and sodas and other snack foods at Delphos’s little gas station, and a new place in the old American Legion hall sells beer and sandwiches and a few other goods. But to do real grocery shopping, the folks in town and the surrounding farms must drive down to Minneapolis, or even farther down U.S. 81 to the larger Salina, 63 kilometers (39 miles) away.

Still, Barry Nelson isn’t despairing. He’s a shepherd of two flocks in Delphos — as the minister at the Living Cornerstone Church and a herder of actual sheep outside of town.

This little town looks prosperous, and it is. But that's because Deadwood, South Dakota, has money to spend that its gambling casinos brought in. (Carol M. Highsmith)

People in the big cities are getting’ tired of the mess that they’re in. And they’re startin’ a migration out of there. They might have to drive in to work n’ stuff, but I think you’re seein’ more and more of that. And I think if we can just hold on, there’s gonna be more people comin’ out of the bigger town gettin’ into the smaller town because it is quieter, there is not as much goin’ on.

They’re not heading to Delphos or hundreds of other little towns in any numbers, though. Not yet, at least.

That’s the reality that led to the Poppers’ extreme metaphor about emptying out the Great Plains and returning it to a “buffalo commons.” Reality has brought hard times to the hope business.

I’ve only touched on what the Carsey Institute calls other “chronically poor” southern communities where people of color are in the majority, or the Appalachian uplands in the East and the Ozark Mountains of Missouri and Arkansas, “where decades of underinvestment have left a legacy of poverty, low education, and broken civic institutions.”

Hard times in the country country are only getting harder there, too.

—

For a terrific visual tour of Delphos, Kansas, via still photographs, check out this compilation on YouTube. You’ll see the town school, now closed, Reverend Nelson’s church, and other places that are quintessential small-town America. All to accompanied by the sound of John Mellancamp’s singing of his “Small Town.”

The Poppers aren't the only one with metaphors for the country country. Ponder this one. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Facetious. Humorous, even flippant, treatment of serious subjects.

Implode. To collapse, or cause something to tumble inward.

Rife. Common, widespread.

One response to “Hard Times in the Country Country”

USA is the greatest brilliant in the world. The nation has had been challenging the universe with new amazing discoveries for the mankind benefit. Why not to build great successive dams in Messesibi river to generate electricity to pull water to the west states rivers to regenerate electricity by building another dams accross those rivers to irrigate the open lands and deserts in the west. There is immpossible in the USA history. I have had loved the USA map since I was student in intermediate school, I kept thinking in some points in the Messesibi river, that we can build the greatest dams. I know that we have had no earthquakes experiences in the great Messesibi river. Whatever the cost is the benefits are greater. Our deserts will be green. I have a dream to pull water from river Zaire to river Nile to Israil and other middle east countries, by building a great dam in some point in the river Zaire, near the river NahrEljur a branch of the White Nile river; the distance is less than 200 km to pull that great water. I have Had another dream to I told for people of Tchad why not to save some of their petrol income to build a great dam in main branch of river Chari, that coming from joint boarders of the two Congos and Central Africa Republic; that is to generate electricity to pull water from the river Zaire to river Chari to save the Lake Tchad. Even that is good for Zaire and the world. The desert is going south fast.