This is the story of a remarkable, and I mean remarkable, man named O.J. Brigance. I will take some time to introduce him so that you fully grasp the enormity of the battle he is fighting.

His enemy, vile and always victorious, is ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the cruel agent of death that took Lou Gehrig, about whom every American sports fan knows.

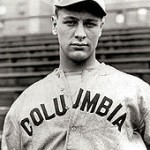

The son of German immigrants living in New York City, Ludwig Heinrich Gehrig was a strapping slugger for the Columbia University baseball team in town. His majestic homeruns caught the eye of the hometown New York Yankees, who in 1923 signed him to a contract and whisked him to the major leagues.

Two years later, Gehrig took over the first-base position, and it would be 14 years before he relinquished it. He played in 2,130 straight games — a record that would stand for 55 years. For good reason, they called him “The Iron Horse.”

But as baseball historian Harvey Frommer relates, Gehrig’s extraordinary career came to a sudden, unexpected, and tragic end:

It was said that “nothing short of a locomotive will stop Lou Gehrig; he will go on forever.” But near the final one-third of the 1938 season the three-time American League [Most Valuable Player] began to falter. As the season ended, no one really knew what was wrong with him. But it was clear that his great strength was waning. His zestful, energetic performance on the playing field had become dulled, muted and lethargic.

The next season, Gehrig was no better. Once, he bent to tie his shoelaces and toppled over. Yet he played on.

But on May 2, 1939, still confused about what had overtaken him, Gehrig benched himself and never played another game. Again, Frommer:

The great Gehrig would tarry a while like a bowed oak. He was still the captain, still the Pride of the Yankees. He brought the lineup card out to umpires before each game, and then from his corner seat in the dugout watched others play baseball.

On June 19th, his 36th birthday, Gehrig got a grim diagnosis at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota: He had ALS, which afflicts just 1 in 50,000 people.

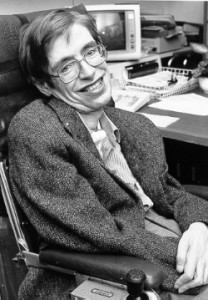

ALS is inexorable and irreversible. The elderly or frail often succumb within months of their first symptoms. Others have survived two decades or more — celebrated British theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, for one, has lived 46 years with the disease, almost totally paralyzed but still functional.

But most ALS patients are dead within five years after the onset of symptoms.

The disease’s very name, broken into parts, explains what befalls them: a: without myo: muscle trophic: nourishment lateral: side (of the spinal cord) sclerosis: hardening or scarring

As KidsHealth online magazine explains, “amyotrophic means that the muscles have lost their nourishment. When this happens, they become smaller and weaker. . . . [T]he disease affects the sides of the spinal cord, where the nerves that nourish the muscles are located; and . . . the diseased part of the spinal cord develops hardened or scarred tissue in place of healthy nerves.”

For reasons not yet fully understood — though there’s a 5- to 10-percent family predisposition to ALS that scientists are studying frantically — motor neurons in the brain that control muscle movements shrink to the point of worthlessness.

ALS patients soon lose the ability to walk, move their limbs, speak, or control many bodily functions. The indignities can be overwhelming to endure and wrenching for friends and loved ones to observe.

“It is not a kind disease,” writes Dudley Clendenin, once a gifted national correspondent for the New York Times, who developed ALS at age 66. “The nerves and muscles pulse and twitch, and progressively, they die. From the outside, it looks like the ripple of piano keys in the muscles under my skin. From the inside, it feels like anxious butterflies, trying to get out.”

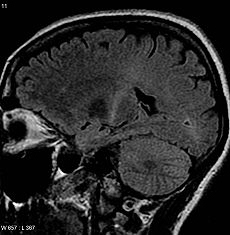

An MRI image of an ALS patient shows increased activity, and not of a good kind, in the motor cortex. (Wikipedia Commons)

One day, ALS patients simply stop breathing because withered thoracic muscles haven’t the strength to properly inflate their lungs. The volume of clean air diminishes to 20-percent levels or less, carbon dioxide fills the lungs, and the patient slips into a sort of narcotic state and dies, usually peacefully. Some ALS patients die earlier from falls or infections.

And at a rate six times higher than in the general population, ALS patients who cannot abide the diminution of life and joy commit suicide, with or without help.

Dudley Clendenin is among the ALS victims who intend to take their lives. “I just have to act while my hands still work,” he writes. “The gun, narcotics, sharp blades, a plastic bag, a fast car, over-the-counter drugs, oleander tea (the polite Southern way), carbon monoxide, even helium. That would give me a really funny voice at the end.

“I have found the way. Not a gun. A way that’s quiet and calm.”

In and of itself, ALS is not painful. But its complications — cramps, burning eyes, pressure sores — can be. Even toward the end, ALS patients can see, hear, feel sensations, and, in most cases, think fully and clearly.

Thinking, tormentedly thinking, day and night, as clearly and intently as you and I.

ALS victims’ lives can be prolonged. Some take the drug Riluzole, which slows the progress of the disease by suppressing and, in effect, sucking up excess toxic glutamate levels in the neurons that are wasting away.

Riluzole only delays the inevitable, however. There is no known cure.

Ventilators can also add months to life, but they require a tracheotomy — an incision into the neck through which a tube is inserted. Patients who choose this option lose the ability to speak, and they require even more caregiver attention.

About 95 percent of ALS patients choose not to go the tracheotomy and ventilator route. They simply cannot afford the crushing costs.

In a scene portrayed by actor Gary Cooper in the 1942 movie “Pride of the Yankees,” Lou Gehrig was honored in a ceremony at Yankee Stadium on July 4th — Independence Day — 1939, about two weeks after his diagnosis. He was embraced by his manager, Miller Huggins, and the team’s other superstar, Babe Ruth.

Then Gehrig walked stiffly to a microphone and spoke, haltingly, to the 60,000 fans in attendance, many of whom wept openly:

“For the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break,” the reticent athlete told the crowd. “Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the Earth.”

Lou Gehrig choked up often during his brief remarks to the crowd that bid him farewell. So did the fans. (AP Photo/Murray Becker)

Gehrig thanked his teammates, the Yankees’ rivals, and his wife, Eleanor. Then he concluded, “I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”

The Iron Horse refused treatment for his disease — not that there was much beyond making a patient comfortable in those days. He remained with the team through the 1939 season, was elected the following season to baseball’s Hall of Fame — which waived the customary five-year waiting period — and even served briefly as a New York City parole commissioner.

“I intend to hold on as long as possible and then if the inevitable comes, I will accept it philosophically and hope for the best,” he told his friends.

When it did come, in his Bronx, New York, home on June 2, 1941, less than two years after his last game with the Yankees, Gehrig was 37 years old.

Before long throughout the United States, ALS was known as “Lou Gehrig’s Disease.”

That was Lou Gehrig, and this is O.J. Brigance:

As a player, O.J. Brigance was a sparkplug, an optimist, a leader. He still is. (www.BriganceBrigade.org)

Now 41, Orenthal James Brigance, a Texan and graduate of Rice University in Houston, was a star football player — a bruising, somewhat undersized linebacker. He played on both National Football League Super Bowl and Canadian Football League champions in the same city: Baltimore, Maryland. His job was clear and violent: he was one of the blockers called on to “sacrifice their bodies,” as they say in the rugged parlance of American football, covering kicks on what are called “special teams.”

Brigance closed out his career with teams in other cities in 2001 and 2002, but the Baltimore Ravens thought enough of the enthusiastic player to bring him back as player-development director, a liaison position between the coaching staff and players.

All was well — superb, in fact — until 2007, when O.J. Brigance began to experience undue fatigue and muscular weakening as he played racquetball with friends and Ravens’ players. The stunning, staggering, inconceivable diagnosis of ALS followed.

From the start, neither O.J. nor Chanda, his wife of 17 years, shrank from the challenge that lay before them. With the Ravens’ encouragement, Brigance not only stuck with his job, he stood before the team to explain what he confronted.

On that day, as ESPN’s “Outside the Lines” program recounted in a profile in 2009, Brigance was more concerned about the staff and players’ feelings than his own. “They were going to have one of the toughest jobs in the league,” he told the sports network. “They had to watch a man walk out of life, right in front of their eyes.”

Think about that comment, which perfectly describes the awful journey of those who must watch the victims of ALS “walk out of life in front of their eyes.”

For a time, Brigance was a terror on wheels. (www.BriganceBrigade.org)

As the disease progressed, Brigance stayed at his post, zipping up and down the corridors at Ravens’ headquarters in a motorized wheelchair to which is attached a portable ventilator, the size of a toaster, that keeps him alive and breathing. Brigance got the wheelchair up to 3.7 mph [5.9 kpm], prompting assistant coach and practical joker Wilbert Montgomery to post “speed limit” signs throughout the building.

Four years into his bout with ALS, Brigance can no longer speak in the usual sense. But two weeks ago, he gave a lengthy, moving, interview to the Baltimore Sun’s Mike Klingaman, in which he conversed via DynaVox, a device whose computer screen displays a typewriter keyboard that O.J. can use, via blinks of his eyes, to converse in words and sentences.

Although Ravens’ head coach John Harbaugh calls O.J. Brigance “the strongest man in the building,” Brigance deflects the compliment. He told the Sun, “I would have to defer to the men and women I see at the facility who, despite their apprehensions about seeing me fight this battle before their eyes, still treat me the same.”

On the blog of the Brigance Brigade — an organization that I’ll explain in a bit — O.J. wrote an entry entitled, “To Bee or Not to Bee.” He began by citing a famous, anonymous quote about a bee, which is aerodynamically too fat to fly but flies anyway because nobody told it it couldn’t. “Unfortunately,” Brigance wrote, “we aren’t bees, so we will always get discouraging reports and run into roadblocks. See them for what they are — opportunities for promotion. Don’t let what you see take your vision.”

Besides Chanda, Lora Clawson, a nurse-practitioner and director of ALS clinical services at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, has been Brigance’s principal caregiver.

“O.J. has decided to live and to fight, to seize the gift of time, and to make every day more meaningful,” she says. “Because of his hopeful idealism, he is a hero to other ALS patients, who otherwise would find it easy to give up and give in.”

Give up? Give in? Not O.J. Brigance. “I actually have good laughs daily,” he told the Sun. “Without the ability to speak, I have become a bit more observant. People are funny about how they approach life.” He has cried just twice, he said. “Back when I was diagnosed, the weight of the diagnosis and possible outcome was hard to accept. The second time was a few months ago, when it was just one of those tough days.”

Every day is a tough day for patients in the advanced stages of ALS. Still, Brigance wrote on the Brigance Brigade blog, “My moment of direction and clarity from my personal despair came while watching the 9/11 memorial service [at Washington’s National Cathedral, following the terrorist attacks in 2001], when President G.W. Bush said, ‘Adversity introduces us to ourselves.’”

And what is the Brigance Brigade? It’s a foundation, begun by O.J. and Chanda Brigance, that partners with the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins. To date, it has raised more than $500,000 to support ALS research and provide some of the frightfully expensive medications, equipment, and support services to patients and their families at the Hopkins ALS Clinic.

And what is the Brigance Brigade? It’s a foundation, begun by O.J. and Chanda Brigance, that partners with the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins. To date, it has raised more than $500,000 to support ALS research and provide some of the frightfully expensive medications, equipment, and support services to patients and their families at the Hopkins ALS Clinic.

Eventually, inevitably, O.J. Brigance could not keep up with all the duties of the player-development job. But, as a senior adviser to his successor, he still goes to his office at the Ravens’ complex four or five times a week, still relates to former teammates and newcomers, and still inspires those around him.

And he still gets around on the motorized wheelchair, although, he jokes, “they took away the keys.” Fact is, Chanda or a nurse must guide him, since he no longer has control of his hands.

Ask yourself if you, in O.J. Brigance’s position four years into the ALS ordeal — my word; Brigance would never use it — if you could look a reporter in the eye and tell him, as O.J. did Mike Klingaman two weeks ago, that you have a “bucket list” of adventures and accomplishments you intend to achieve. “I would like to go to Africa on safari,” he said. And “see Mount Rushmore and write a book.”

He said this, remember, with the blink of an eye.

Even before you know his story, O.J.'s smile is inspiring. (www.BriganceBrigade.org)

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Indignity. A humiliating or degrading experience or remark.

Inexorable. Impossible to stop. Relentless.

Vile. Repulsive, disgusting, horribly unpleasant.

7 responses to “ALS Conquers, but Does Not Diminish, All”

[…] Voice of America (blog) […]

You might want to look at this: http://www.cnn.com/2011/09/28/health/early-als-trial-results-encouraging/index.html?hpt=he_c2

Dear Brendon,

I have indeed looked at the story whose url you sent along, and I urge my readers to do so as well. It’s a report about a promising trial involving ALS, on too small a scale to be labeled a breakthrough as yet, but a sign that researchers might be closer to identifying a — I hesitate to use the word cure — against the terrible disease.

Ted

You wrote beautifully until you talked about ventilators. It doesn’t add months but in most cases many years. You’re also incorrect about speech because if someone can speak before the procedure there is no reason they cannot after. Typically the reason this happens is bad assumptions by their doctors. I know because I have ALS and have been on a vent for nearly 14 years. I also know many people like me who have extremely happy and fulfilling lives.

Dear Jeff,

I certainly bow to your knowledge of the subject and rejoice that you are happy. A lot of people with less confronting them are not. My very best to you.

Ted

O.J. Brigance is a true inspiration. Many are unaware of what ALS is and how much it has an impact on our lives. I commend you for a great visual presentation through words, you gave such a detailed and emotional explanation about the disease and incorporated stories of our heroes. I would love to link your article to my facebook page that advocates to help fight the disease. I am a student of Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This year in my Entrepreneurial Marketing class we have been given an assignment that runs thought the semester to choose an organization of your choice. My team and I have chosen to support the ALS foundation through spreading awareness to our fellow students and the surrounding community. We are holding a series of events and so far we have raised a little over $300.00 to the cause 🙂 !!! This is the link to our facebook page to check out http://www.facebook.com/pages/Temple-ALS-Foundation/221027704622070 !

Just thought you would appreciate our support and you would be interested in our story!

Thanks again for such a great article !

Dear Amanda,

Indeed I do appreciate and applaud your story. Sorry to take so long publishing it. I’ve been away, galloping around the country!

Ted