Children’s first exposure to the freedoms that Americans cherish sometimes comes not from kindly parents or wise teachers, but from an obnoxious jerk insulting someone or cursing at something. Ranting till the veins bulge in his neck.

If confronted, the loudmouth snaps back, “Yeah, well, it’s a free country.”

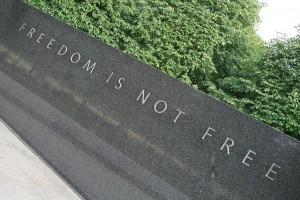

Indeed it is, as we reminded ourselves and the world during our Independence Day festivities this past weekend. Not only do we treasure — and millions elsewhere long to enjoy — our freedoms, but our heroes all too often die to preserve them.

As a simple statement, etched on a wall abutting the contemplative Pool of Remembrance at the Korean War Veterans Memorial here in Washington reminds us, “Freedom is Not Free.”

Before all else, the Bill of Rights appended to the U.S. Constitution guarantees Americans’ freedom of speech. But tension is growing between that right and words that offend — or used to offend when we were less tolerant of gutter talk and lewd behavior.

In 1919, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that while freedom of speech is exalted, it is not unlimited. We may not shout “Fire!” in a crowded theater. Nor, according to a later ruling, may we legally burn a cross on a person’s lawn or incite a crowd to violence.

Yet burning an American flag, equally loathsome to some, is considered a permissible exercise of free speech.

Some anti-gay protestors have chosen the funerals of U.S. service members at which to make their point. (@mjb-fl, Flickr Creative Commons)

In the 1970s, hate-spewing neo-Nazis were given the OK to march through Skokie, Illinois — where one in six residents was a Holocaust survivor. The Nazis never showed up, but the Reverend Fred Phelps and his followers are much in evidence in equally volatile surroundings today. Phelps is a disbarred lawyer and self-styled Baptist preacher — self-styled because no Baptist denomination recognizes him. He and his followers despise gay people. “God hates fags,” they scream — most provocatively and insensitively at the funerals of U.S. servicemen and women killed abroad.

Whether or not the soldiers are thought to be gay, the Phelps brigade attributes their deaths to God’s wrath against Americans for tolerating homosexuality.

And into this volatile mix have roared muscular motorcyclists, calling themselves the “Patriot Guard Riders.” They menace Reverend Phelps and his crowd — escalating already-raw emotions at what were supposed to be solemn farewells to the nation’s heroes.

Neo-Nazis marched on the federal building in Phoenix, Arizona, last year to protest a judge's decision to weaken anti-immigrant legislation. (JohnKit, Flickr Creative Commons)

Courts have steadfastly protected Reverend Phelps and his followers’ right to assemble and speak, however vilely. But in many cases they have imposed a no-picketing buffer zone between the Phelps crowd and mourners. Nonetheless, one cannot miss their coarse chanting at 46 meters (150 feet).

Just how hateful can speech be and still be protected? Read on.

In 2006, a federal appeals court in Philadelphia struck down a law aimed at shielding children from Internet pornography. The court affirmed earlier decisions that even though pornography offends most people, porn on the Web is free speech, protected by the First Amendment.

In many Internet mailboxes — including some easily accessed by children — what used to be a trickle of unsolicited porn advertisements has turned into a torrent. In part, that’s because the Internet has become a plum market for pornographers. A few years ago, Datamonitor, a New York-based research company, estimated that Internet users spend more than $3 billion a year paying to see porn on increasingly explicit websites.

Looking for still more customers, porn website owners are inundating the Net with what is called “porn spam” — often laced with graphic sexual photographs — as a tease to visit paid sex websites. They fire off spam like a random shotgun blast to millions of e-mail addresses at once. Read the rest of this entry »