Posted May 24th, 2011 at 7:21 pm (UTC-4)

Like a pesky fly that neither swatter nor sledgehammer can seem to catch and crush — or a hero who lived to fight another day in cliffhanger movie serials a couple of generations ago — undermanned but determined Confederate forces kept eluding certain destruction in the first two years of the American Civil War.

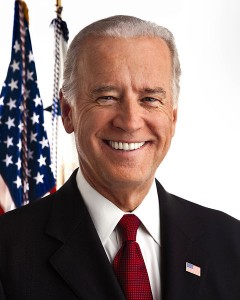

Robert E. Lee and his handsome, gray horse Traveller were unmistakable on the battlefield. (Library of Congress)

When last we left it, the army of General Robert E. Lee had fallen back from a northern incursion at Maryland’s Antietam Creek, and blunted the North’s expected kill shots at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville in Virginia.

Then Lee seemed to disappear while one inadequate Union commander after another lost face and his command, and Yankee forces milled about the environs of Washington wondering where Lee had gone.

Where he was heading was straight for the heart of northern territory once again.

Gettysburg

A hill called Little Round Top, shown here in a painting by Edwin Forbes, was the scene of an unsuccessful Confederate attack at Gettysburg. (Library of Congress)

July 1-3, 1863. What American does not know of this little Pennsylvania town and the momentous battle fought there? One hundred-sixty thousand men engaged. The survival of one nation, indivisible, north and south, in the balance. The Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, the Angle, and Pickett’s Charge, as legendary places where the great armies crashed together on this sprawling battlefield.

When the almost accidental clash of two great armies had played out, 7,000 soldiers lay dead. The Confederates’ last thrust to — as a Georgia private pledged — “let the Yankey Nation feel the sting of the War” ebbed forever in bayonet-to-bayonet combat on Cemetery Ridge.

Gettysburg is the story of Robert E. Lee, wondering after J.E.B. Stuart, his dashing cavalry general who was gallivanting about the countryside; ordering General George Pickett’s suicidal charge with the vow, “I will strike him there”; disconsolately telling survivors, “All this has been my fault”; and sealing the nascent southern nation’s fate by leading his defeated army back south, into Virginia, for a second — and last — time.

Gettysburg would forever be remembered as “the High-Water Mark of the Confederacy.” So pivotal was the battle there that 1,400 monuments and memorials, as well as the resting place of thousands of Union dead, would be consecrated on that field.

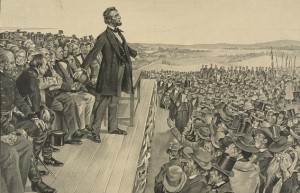

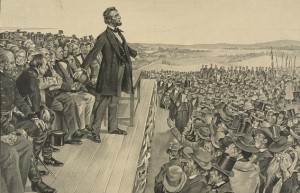

Desperate for a knock-out blow and rejoicing when it came, Washington arranged a day of proud, but somber, speeches for the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg in November.

A fine band and a bombastic orator — former Harvard University president Edward Everett — were booked for the occasion. Almost as an afterthought, squeaky-voiced President Abraham Lincoln was invited to say a few words as well.

They would be few, all right. Lincoln’s 256 words, delivered in just over two minutes to an audience that wasn’t entirely sure the president was even speaking and was astonished to see him done, became some of the most famous remarks in American, perhaps world, history.

Many an American schoolchild has been asked to memorize and recite the entire speech, [1]beginning with Lincoln’s “Four score and seven years ago” reference to the founding of the American nation — and closing, as Lincoln did, with a resolution that the dead who lay buried before him had not died in vain and that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Chickamauga

September 19-20, 1863. Gettysburg may have been the Confederacy’s zenith in what its people called “the War of Northern Aggression,” but “The South’s Last Hurrah” came along a stream called Chickamauga, an Indian word that fittingly means “River of Death.” Having abandoned Chattanooga, Tennessee, on the strategically vital Tennessee River, General Braxton Bragg’s Rebel army faced the Federals in rugged terrain on the Tennessee-Georgia border in the southernmost reaches of the long Appalachian Mountain chain. These battle-hardened forces won the bloody fight and drove the Yankees back to Chattanooga in disarray.

Chattanooga

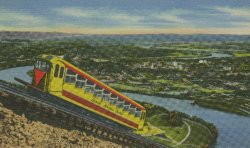

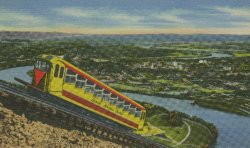

This is a 20th-Century view of an incline railway on Lookout Mountain, but it gives you an idea of the terrain that Yankee soldiers overcame in climbing up and overtaking the enemy artillery that commanded this formidable perch. (Library of Congress)

November 23-25, 1863. After smashing Union general William “Old Rosy” Rosecrans at Chickamauga, Bragg’s Confederate Army of the Tennessee retook Lookout Mountain, an imposing redoubt from which he shelled Federal forces that had captured Chattanooga, 670 meters (2,200 feet) below. But on November 24th, Yankee troops’ brazen and victorious charge up the fog-swept mountain ousted the Confederates and assured continued Union control of the key city on the Tennessee River.

Andersonville

February 1864. This was not a battle site, but rather an unpleasant extension of clashes throughout the campaign. Built to house 10,000 Union captives, it was Andersonville Prison — which the Confederates called “Camp Sumter” after its location in Sumter County, Georgia. Read the rest of this entry »