Over the last five decades the Islamic Republic of Mauritania has gone through profound climatic and demographic changes. In 1960, when Mauritania won her independence from France, over 60% of all Mauritanians were nomads, and the capital city of Nouakchott was home to only 500 persons. (The first president of Mauritania, Moktar ould Daddah, initially lived in a khaima, a traditional tent, which he had installed on the grounds of what is now the Presidential Palace). Today, only 5% of Mauritanians remain nomads, and the population of Nouakchott has mushroomed to around one million people. This rapid sedentarization, caused by a series of lengthy droughts that started in the late 1960s, had dramatic economic and social consequences. Nomadic patrilineages, which for generations had lived off their camel herds and date palms, spread throughout West and Central Africa, supporting their families with dry-goods stores. Other tribes, who for centuries survived through ‘razzias’ (cattle raids) and their military prowess, took over Nouakchott’s black market in foreign currency, while still others monopolized the trade in imported cars.

These deep changes in Mauritanian life over the last half-century have been accompanied by important transformations in the form, content and context of Moorish music. In 1960, most Moorish griots were still attached to the rural ‘tents’ of warrior chiefs. (The three principal warrior emirates, or tribal confederations, were located in the Hodh [eastern Mauritania], in the Tagant [central Mauritania], and in the Trarza/Brakna [southwest Mauritania], and the majority of griot families have roots in these regions). Today, the overwhelming majority of all Moorish griots live in Nouakchott, and the electric guitar has replaced the tidinit (5-string lute).

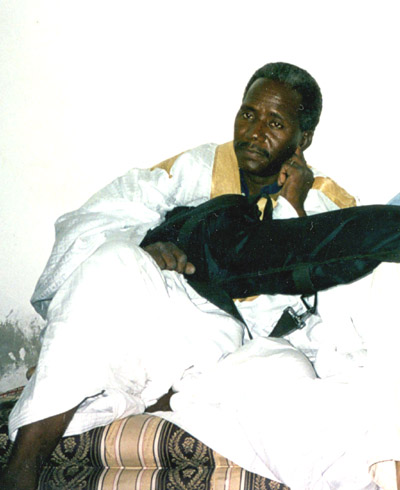

Few musicians have been as central to these changes as Hammadi ould Nana. Hammadi was born in the winter of 1957/1958 in Tidjikja, the capital of the Tagant region, and was named after his paternal grandfather, who came to Tidjikja from eastern Mauritania, sometime in the 1920s. The young Hammadi was initiated to the secrets of the tidinit by his father Khalife, who had himself, mastered the instrument during his years of apprenticeship in Néma, the capital of the Hodh Ech Chargui region. (The griots of the two Hodhs, the regions closest to the Malian border, are generally considered to be the best tidinit players in Mauritania). Another of Hammadi’s earliest musical influences was his paternal grandmother, who led a group of three female singers, who performed a repertoire of very rhythmic dance songs.

By the age of 9, Hammadi was accompanying Khalife to weddings and naming-ceremonies, and by the age of 17, he had started performing throughout Tidjikja with his sister Nibqiha, and a chorus of female singers. And although Hammadi had learned a good deal of the traditional tidinit repertoire, (which consists of hundreds of ‘songs’/melodies, often with set lyrics, and regional associations) he was more inspired by the dance rhythms of Haratin ‘folk’ music. (The Haratines, or ‘black Moors’, are the descendants of the sub-Saharan slaves who were the vassals of the Bidan, or ‘white Moors’. The Haratines speak the same language as the Bidan [Hassaniya], and share much of their culture, but have their own rich ‘folk’ music tradition).

In the late 1960s, Hammadi discovered the six-string guitar. One of his cousins had come to Tidjikja from Néma, to study the tidinit with Khalife, and had brought the strange new instrument with him. When his cousin left Tidjikja several months later, the guitar did not leave with him. Over the next couple of years Hammadi started to develop a unique repertoire of guitar melodies; a repertoire that both conformed to the strict modal structures of Moorish music, and drew on Haratin folk rhythms. Running his acoustic guitar through a radio amplifier, and accompanied by his sister, several percussionists, and a chorus of female singers, Hammadi was starting to develop the sound that would make his name.

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_two.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana playing amplified acoustic guitar

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_three.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana playing amplified acoustic guitar

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_six.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana & Nibqiha mint Nana

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_eight.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana & Nibqiha mint Nana

In 1974, Hammadi left Tidjikja and moved to Nouakchott. One night, several months after his arrival in the capital, a car stopped in front of the house and two men asked for Hammadi. They were organizing a small party and wanted Hammadi to perform for their guests; this performance was his first recording. Two years later, one of Hammadi’s ‘relatives’ (a member of his Idaw ‘Ali tribe from Tidjikja), brought Hammadi an electric guitar and an amplifier. Hammadi found in the sonic qualities of the electric guitar (sustain, controlled distortion) the final ingredients he needed to spice up his ‘hot’ dance repertoire.

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_four.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_five.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_seven.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_ten.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana

By the late 1970s, Hammadi had become one of the most in-demand musicians in Mauritania, and his guitar repertoire had become the blueprint for the next generation of griots. In 1982, however, a terrible car accident almost brought Hammadi’s career to an end; he lost both of his parents in the crash, and didn’t return to performing for several years. Encouraged by his fans, Hammadi eventually returned to performing; although he hasn’t sung publicly since the accident. Today, Hammadi lives in Nouakchott and continues to perform throughout Mauritania.

Hammadi has made virtually no recordings for Mauritanian radio or television, but there are dozens of his recordings available in Nouakchott’s cassette stalls (these are all copies of cassettes that were made at weddings), and possibly hundreds of private recordings owned by his patrons. All of the tracks presented here, with one exception (this next track, which I recorded), were taken from cassettes purchased in Nouakchott’s market stalls.

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/hammadi_nine.Mp3] Hammadi ould Nana

The biographical outline presented here is drawn from a long interview I conducted with Hammadi in Nouakchott, on May 21, 2003.