When I first started, twenty years ago, to explore the musics of Africa, recordings of many popular African styles, and detailed information about them, were hard to come by. Today, thanks especially to the generous efforts of dedicated African music bloggers (all of whom are more prolific than I am), there is a wealth of terrific recordings from throughout the continent available at the click of a mouse. However, the history of much of the continent’s popular music still remains to be told. Throughout all of Africa, the 20th century was a time of explosive musical creativity; similar historical processes and cultural interactions saw the birth of countless styles and genres across the continent. Whether you’re a relatively new initiate to the joys and wonders of African music, or have been chasing after recordings for decades, there are still many mysteries left to unfold.

As I have tried, over the years, to grasp the breadth and diversity of African musical expression, studying the intricacies of individual genres, in order, ultimately, to understand the relationships between Africa’s different musical microclimates and a larger creative ecosystem (continental and intercontinental, encompassing both Africa and her Diaspora), I have often been confused and frustrated by ‘fuzzy vocabulary’, by names that have multiple meanings, different histories in different times and places.

For example, what exactly do you call the popular musics of the two Congos? Does the term Rumba refer to all of the popular musics of the last six decades, or does it only refer to the sung verses before the sebene, or both? Does the name Soukous mean anything to music fans in both Congos? Can you appropriately call the Mutuashi recordings of Tshala Muana ‘Rumba’ music? Is the ‘Highlife’ a dance, or does the name refer rather to a context of production (i.e. society dance clubs and concert parties), or to a distinct musically identifiable style? Does the name Highlife mean the same thing in Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Senegal or Cameroun?

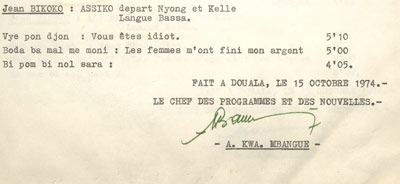

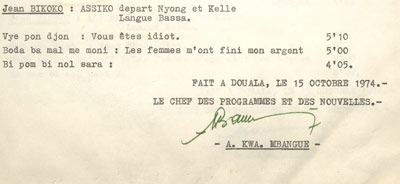

Another example is the ‘Assiko’. I know of a Senegalese percussion style called Assiko, that may have had its roots in Sierra Leone- where I have also heard of Assiko percussion- recently the Gangbe Brass Band from Benin named one of their albums ‘Assiko’, and in Cameroon there have been at least three different genres of Assiko, sung in different languages with different histories and different offshoots. About a month ago I started going through a set of reels that Radio Doula gave us back in 1974 and a large stack of Cameroonian vinyl, and the more I listened (especially to the recordings of one Jean Bikoko Aladin) the more I yearned for taxonomic clarity and a deeper knowledge of Assiko. Now, several weeks of phone calls and interviews later, here is what I learned about Cameroonian Assiko music and especially about the gifted Jean Bikoko Aladin.

Today, to speak of Assiko music in Cameroon is to speak of the music of the Bassa people from Southern Cameroon. The foundations of Bassa Assiko are the interconnected relationships between the glass bottle and the guitar, and between the earth and the feet; the name Assiko is derived from the Bassa words ‘Issi’ for earth and ‘Go’ for foot. Assiko, like so much of 20th century African music is a syncretic form; it developed, probably over one hundred years ago, when the acoustic guitar, first brought to Cameroon by Portuguese sailors, was married to the Ngola rhythm of the Bassa.

Over the first half of the 20th century Assiko music was the rhythm of celebrations throughout Bassa country, performed by guitar players who traveled the Assiko circuit that took them to Eséka, Mésondo and Edéa, and through all of the villages in between, with detours to the Bassa neighborhoods of Douala. These migrant guitar players, accompanied by a percussionist keeping the pulse on a glass bottle beat with two iron rods, kept Bassa audiences dancing late into the night. And it was on this circuit, performing his way through the villages of Bassa land, that Jean Bikoko Aladin cut his teeth.

Considered the father of modern Assiko music, Jean Bikoko Aladin is one of Central Africa’s great unsung guitar masters. He was born around 1939 (his actual date of birth is unknown) in a village not far from Eséka. After a few years of elementary school at the Catholic Mission in Eséka, Jean Bikoko left his family to find work, and while still in his mid-teens was hired as a cook and servant for a logger in the forest village of Bonepoupa, located 65 miles northwest of Eséka. It was in Bonepoupa that Jean Bikoko first tried his hand at the guitar, building his own rudimentary instrument out of bamboo and bark, and studying the techniques of local guitar players Albert Dikoumé and Hiag Henri.

From Bonepoupa, Jean Bikoko moved to Songmbenguè, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Edéa, where he hauled cinderblocks on construction sites during the day, and entertained at night with his guitar. Frustrated by the difficulties of making a living in Songmbenguè, Jean Bikoko soon moved to Douala, hoping that fate would smile on him in Cameroon’s economic capital. And fate did, when not too long after his arrival he met Alexandre Ekong, a guitar player who performed regularly on Radio Douala. With Ekong’s guidance, Jean Bikoko made his way into the Radio Douala studios, and in the early 1960s (I can’t confirm the date) made his recording and broadcast debuts. Within a short time his Assiko rhythm was a listener favorite.

Impressed by Bikoko’s guitar playing and the enthusiastic audience response, Radio Douala’s recording engineer Samuel Mpoual joined forces with Joseph Tamla (a businessman with stores in Douala, Yaounde and Bafoussam) to launch the Africambiance record label. The label would release 75 Jean Bikoko Aladin singles; Africambiance also released singles by Anne-Marie Nzié, and a variety of modern and traditional groups from throughout Cameroon. All of Jean Bikoko’s Africambiance singles were recorded at the Radio Douala studios, with the master tapes then sent to a pressing plant in France.

With the revenue from his many singles and residencies at several of the most prestigious nightclubs in Douala and Edéa, the 1960s were a prosperous decade for Jean Bikoko. In a 2003 interview, he told the Cameroonian journalist Noé Ndjebet Massoussi that, ‘I made so much money (in the early 1960s) in Edéa, that I was marrying five women a day. By the time I left the town I had forty seven wives’. In 1972, still flush with cash, Jean Bikoko opened his own hotel and restaurant in his hometown of Eséka. In 1969, he represented Cameroon at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algeria, and in 1977, he participated in the FESTAC in Lagos, Nigeria. Jean Bikoko’s golden years lasted until the end of the decade. In the 1980s, however, a new generation of Assiko stars started to shine, musicians like Samson Chaud Gars and Kon Mbogol Martin, both of whom were inspired by Jean Bikoko Aladin.

Although Jean Bikoko would make a few recordings over the next two decades, with notably a few hits in the 1990s, his time in the limelight had come to an end. By the time Noé Ndjebet Massoussi went looking for Jean Bikoko Aladin in Eséka, in 2003, the Assiko legend was trying to keep the power from getting cut to his now rundown bar where he still played on weekends (the hotel and restaurant he built in 1972 burnt down decades ago). The last half-dozen years have seen, however, the resurgence of Jean Bikoko Aladin (his fretboard wizardry earned him the Aladin nickname). In 2003, the Belgium based producer Victor Bidjocka bi Kon brought Jean Bikoko back into the studio for the first of two releases that have appeared on his Sun City Productions label (the first release is called ‘Ruben Um Nyobé’, and the second is ‘Kel Ma Wo’). And just this summer Jean Bikoko performed in Brussels, Paris (at the Zénith), Lyon, and in Germany; Sun City Productions will be releasing a DVD of the Brussels performance this fall.

This first set of four tracks was given to the Voice of America by Radio Douala back in 1974 and features some of Jean Bikoko’s earliest recordings. I haven’t been able to identify dates for any of these tracks; in the absence of written records, none of my interlocutors could recall when individual songs were recorded. These radio recordings could all have been made in the early 1970s, just as they could be archival recordings that Jean Bikoko made in the 1960s. Regardless, all of these tracks illustrate Bikoko’s effortless virtuosity and rhythmic punch. All of the recordings were made live in the Radio Douala studios with one microphone running into a Nagra, with engineer Samuel Mpoual at the controls (I tried to track down Mr. Mpoual, but it seems he passed away in 2000).

First up is ‘Mawan Na Ndong Len’, which opens with Jean Bikoko saying, ‘these days there are no longer any real friends’. This theme, however, is not developed in the rest of the song. In between guitar riffs Jean Bikoko repeats the question, ‘what am I going to do since I’ve come to this meeting?’ Assiko has always been, first and foremost, dance music, and this track is a good example of how Jean Bikoko got his fans on their feet. Before Jean Bikoko came on the scene the Bassa danced the Assiko with their elbows and their torso, with individual dancers taking turns in front of the musicians. Jean Bikoko was the first Assiko musician to tour with a group of dancers who put on an ‘Assiko show’; a show that featured a new style of dancing that shifted the dancer’s center of gravity south to the hips and buttocks. Jean Bikoko’s dancers were also the first to wear the ‘pagne’-the wraparound skirt-with a rolled waistband, an innovation that accentuated the rocking of the hips.

This next song ‘Bi Pom Bi Nol Sara’ may have been recorded in the early 1970s. Jean Bikoko mourns his friend Sara who was killed in unusual circumstances, and asks the police to open an investigation. Traditionally, Assiko guitarists played both the bass and lead parts; Jean Bikoko was the first to bring in another instrument to provide the low-end foundation. At various times he experimented with a bass xylophone, a large three-key sanza or bass-box, and an upright string bass. It sounds to me like these radio recordings all feature the bass-box.

‘Vye Pon Djon’ is a particularly enjoyable track. This song was originally composed by the Assiko guitar player Minka, from the district of Bot Makak, which is about thirty miles north of Eséka. Jean Bikoko sings, ‘he is really foolish. He doesn’t know me’.

- [audio:http://www.voanews.com/MediaAssets2/projects/african_music_treasures_blog/JEAN_BIKOKO_ALADIN_R_Vye_Pon_Djon.Mp3] Jean Bikoko ‘Vye Pon Djon’

‘Boda Ba Mal Me Moni’ is another lamentation. Jean Bikoko tells the story of the day he was robbed. He sings, ‘I was robbed for no reason. What I am going to do? I am wallowing in misery. I was robbed for no reason’.

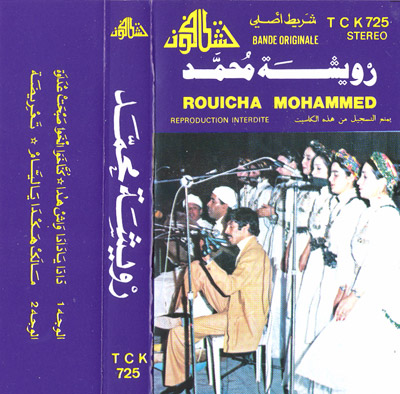

This next group of songs were also recorded by Samuel Mpoual at the Radio Douala studios, and then commercially released on the Disque Africambiance label. As a whole they sound a little more saturated than the radio recordings but feature some terrific playing (we have a couple dozen Africambiance singles and many of them are pretty terrible pressings). If you look at the record labels you’ll notice they list ‘Jean Bikoko et son Ensemble Federal 67’. I don’t know if the group’s name refers to the year these recordings were made.

In ‘Bonlana Man Ma Nan’ Jean Bikoko remembers and mourns the Cameroonian nationalist leader Ruben Um Nyobé. Although today overshadowed by the likes of Nkrumah, Kenyatta, and Lumumba, Ruben Um Nyobé was one of pre-independence Africa’s great nationalist leaders; and he is in particular a hero to the Bassa people. Um Nyobé was born in 1913, in the village of Song Peck, in the Eséka district and went on to become one of the leaders of the UPC (l’Union des Populations du Cameroun), a political party that fought politically, and eventually militarily, for Cameroon’s total independence from France and Great Britain. Ruben Um Nyobé was killed by the French army in September of 1958, and remains a hero to the Bassa people.

‘A Ma Wanda Boga Bes’ was probably composed soon after Um Nyobé was killed. The title can be translated as ‘let’s go out of the forest’ and this song calls all of the UPC freedom fighters, who were hiding and fighting in the forests of Bassa land with Um Nyobé, to come out of the forests and return to their villages, to continue the struggle for independence through political means.

These final two tracks are more lighthearted. In ‘Nje A Gwe Lilog Li Man?’ Jean Bikoko expresses his astonishment at the health and beauty of a young baby. He sings, ‘who does this chubby little baby belong to?’ And in the final track ‘Papa Ngono Njok’ Jean Bikoko jumps from theme to theme, singing about the beauty of a young girl, and the beauty of nature. This is another showcase for his driving guitar and pulsing Assiko groove.

Jean Bikoko Aladin’s music continues to influence a new generation of Assiko artists, from the Paris based Assiko player Kristo Numpuby and the Douala based Yvette Bassoga, to the successful ‘crossover’ Bassa singer Blick Bassy. But perhaps even more than his guitar playing it is his showmanship that has changed Assiko music. Today, Assiko dance performances are a mainstay of Cameroonian cultural festivals, and specialized Assiko clubs in Douala and Yaoundé feature very popular acrobatic Assiko dance troupes. (To get an idea of the modern Assiko dance show check out the videos of the Olivier de Clovis Assiko group on Youtube).

This post was based on interviews with Francois Bingono Bingono, Blick Bassy, and Noé Djebet Massoussi (a lot of the biographical detail on Jean Bikoko’s life comes from a 2003 feature that Noé published in ‘Le Messager’). A very special thanks to Mr. Paul Bikoi for his help translating the songs, and for sharing his memories of Jean Bikoko Aladin’s golden era with me.