This is the story of a remarkable, and I mean remarkable, man named O.J. Brigance. I will take some time to introduce him so that you fully grasp the enormity of the battle he is fighting.

His enemy, vile and always victorious, is ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the cruel agent of death that took Lou Gehrig, about whom every American sports fan knows.

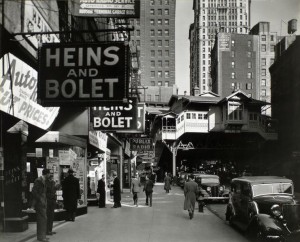

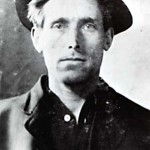

The son of German immigrants living in New York City, Ludwig Heinrich Gehrig was a strapping slugger for the Columbia University baseball team in town. His majestic homeruns caught the eye of the hometown New York Yankees, who in 1923 signed him to a contract and whisked him to the major leagues.

Two years later, Gehrig took over the first-base position, and it would be 14 years before he relinquished it. He played in 2,130 straight games — a record that would stand for 55 years. For good reason, they called him “The Iron Horse.”

But as baseball historian Harvey Frommer relates, Gehrig’s extraordinary career came to a sudden, unexpected, and tragic end:

It was said that “nothing short of a locomotive will stop Lou Gehrig; he will go on forever.” But near the final one-third of the 1938 season the three-time American League [Most Valuable Player] began to falter. As the season ended, no one really knew what was wrong with him. But it was clear that his great strength was waning. His zestful, energetic performance on the playing field had become dulled, muted and lethargic.

The next season, Gehrig was no better. Once, he bent to tie his shoelaces and toppled over. Yet he played on.

But on May 2, 1939, still confused about what had overtaken him, Gehrig benched himself and never played another game. Again, Frommer:

The great Gehrig would tarry a while like a bowed oak. He was still the captain, still the Pride of the Yankees. He brought the lineup card out to umpires before each game, and then from his corner seat in the dugout watched others play baseball.

On June 19th, his 36th birthday, Gehrig got a grim diagnosis at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota: He had ALS, which afflicts just 1 in 50,000 people.

ALS is inexorable and irreversible. The elderly or frail often succumb within months of their first symptoms. Others have survived two decades or more — celebrated British theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, for one, has lived 46 years with the disease, almost totally paralyzed but still functional.

But most ALS patients are dead within five years after the onset of symptoms.

The disease’s very name, broken into parts, explains what befalls them: a: without myo: muscle trophic: nourishment lateral: side (of the spinal cord) sclerosis: hardening or scarring

As KidsHealth online magazine explains, “amyotrophic means that the muscles have lost their nourishment. When this happens, they become smaller and weaker. . . . [T]he disease affects the sides of the spinal cord, where the nerves that nourish the muscles are located; and . . . the diseased part of the spinal cord develops hardened or scarred tissue in place of healthy nerves.”

For reasons not yet fully understood — though there’s a 5- to 10-percent family predisposition to ALS that scientists are studying frantically — motor neurons in the brain that control muscle movements shrink to the point of worthlessness.

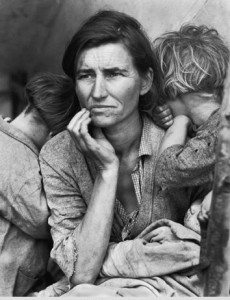

ALS patients soon lose the ability to walk, move their limbs, speak, or control many bodily functions. The indignities can be overwhelming to endure and wrenching for friends and loved ones to observe.

“It is not a kind disease,” writes Dudley Clendenin, once a gifted national correspondent for the New York Times, who developed ALS at age 66. “The nerves and muscles pulse and twitch, and progressively, they die. From the outside, it looks like the ripple of piano keys in the muscles under my skin. From the inside, it feels like anxious butterflies, trying to get out.”

An MRI image of an ALS patient shows increased activity, and not of a good kind, in the motor cortex. (Wikipedia Commons)

One day, ALS patients simply stop breathing because withered thoracic muscles haven’t the strength to properly inflate their lungs. The volume of clean air diminishes to 20-percent levels or less, carbon dioxide fills the lungs, and the patient slips into a sort of narcotic state and dies, usually peacefully. Some ALS patients die earlier from falls or infections.

And at a rate six times higher than in the general population, ALS patients who cannot abide the diminution of life and joy commit suicide, with or without help.

Dudley Clendenin is among the ALS victims who intend to take their lives. “I just have to act while my hands still work,” he writes. “The gun, narcotics, sharp blades, a plastic bag, a fast car, over-the-counter drugs, oleander tea (the polite Southern way), carbon monoxide, even helium. That would give me a really funny voice at the end.

“I have found the way. Not a gun. A way that’s quiet and calm.”

In and of itself, ALS is not painful. But its complications — cramps, burning eyes, pressure sores — can be. Even toward the end, ALS patients can see, hear, feel sensations, and, in most cases, think fully and clearly.

Thinking, tormentedly thinking, day and night, as clearly and intently as you and I.

ALS victims’ lives can be prolonged. Some take the drug Riluzole, which slows the progress of the disease by suppressing and, in effect, sucking up excess toxic glutamate levels in the neurons that are wasting away.

Riluzole only delays the inevitable, however. There is no known cure.

Ventilators can also add months to life, but they require a tracheotomy — an incision into the neck through which a tube is inserted. Patients who choose this option lose the ability to speak, and they require even more caregiver attention.

About 95 percent of ALS patients choose not to go the tracheotomy and ventilator route. They simply cannot afford the crushing costs.

In a scene portrayed by actor Gary Cooper in the 1942 movie “Pride of the Yankees,” Lou Gehrig was honored in a ceremony at Yankee Stadium on July 4th — Independence Day — 1939, about two weeks after his diagnosis. He was embraced by his manager, Miller Huggins, and the team’s other superstar, Babe Ruth. Read the rest of this entry »