Before I begin, a quick note: Carol and I will be off on another of our madcap excursions across the country — or part of it — for two weeks or so. One the places we hope to visit is New Orleans, which was devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. I believe it has come back, maybe not all the way, but impressively. And I hope to tell you about it when I return.

Meanwhile, read on here about “Freedom, Expressed.” And later if you like, feel free to fish in the archives in the column to the right and learn about some of my, and Carol’s, other adventures.

—

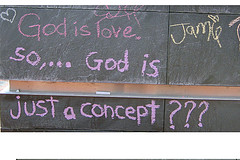

This is about freedom and a wall. And it’s not the Berlin Wall.

To the right, you see two women writing on this wall. They’re Egyptians, and they’re a long way from home. The women visited the United States a couple of weeks ago as part of an adult exchange program called “Friendship Force,” in which travelers — or “ambassadors” as the nonpolitical, nonsectarian organization calls them — stay with hosts in any of 60 countries.

According to its Web site, Friendship Force International “serves those who love to explore the world, meet diverse people, and be with them to learn and understand more about their lives and share their own.”

The Egyptian women were visiting with chapter members in Charlottesville, Virginia. And that’s where freedom and the wall come in.

Charlottesville is the hometown of Thomas Jefferson, the author of America’s Declaration of Independence. His friend James Madison, who wrote the first constitutional amendments called the “Bill of Rights,” also lived nearby.

The First Amendment, guaranteeing freedom of speech, is the only permanent inscription on the wall in question.

It’s a giant, two-sided slate chalkboard — reminiscent of a classroom blackboard but much, much larger — called the “Freedom of Expression Monument,” 2 meters high by 18 meters wide, that stands in a little triangular park at one end of Charlottesville’s pedestrian mall.

A steel podium, like the public soap box at London’s Hyde Park, is built into the monument. The monument directly faces City Hall and sculptures of three American founding fathers from the area: Madison, James Monroe (another “founding father” and president), and Jefferson, whose words are said to have inspired the erection of the wall:

The will of the people is the only legitimate foundation of any government, and to protect its free expression should be our first object.

The idea for what some call the “freedom wall” and others, the “community chalkboard,” originated with the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression. It’s a 21-year-old nonprofit organization based in Charlottesville that sees itself as a watchdog of free speech and press.

Robert O’Neill, a former president of the University of Virginia, was the center’s director at the time the wall was being planned. He said, “To capture a quintessentially Jeffersonian concept, truth should be left free to be pursued, so long as there is the opportunity for refutation, rebuttal, and counter-speech. And that exists in abundance on this physical open forum.”

Seeking an innovative concept for a monument to free expression, the Jefferson Center sponsored a contest. The winner was the community chalkboard design by two Charlottesville architects, Robert Winstead and Peter O’Shea. Winstead has said he and his friend had in mind the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, where people take rubbings of the names of loved ones and leave mementos.

In other words, he told me, they wanted more than something to look at and admire.

We have lots of monuments to heroic figures and to great events in our history. But almost all of them are kind of object monuments meant to be viewed from afar and not really interacted with.

The wall’s creators were unapologetic about the possibility that not just noble speech and civic discourse — but also obscenity and venomous thought might be written for all to see. They’d rather have racism, other hatreds, and outrages — real or imagined — discussed in a public forum, “than have them kind of festering in back yards and back rooms where they can become dangerous,” Winstead told me.

In March of 2001, Blake Caravati, a local builder who was Charlottesville’s part-time mayor and also one of five city council members, voted to approve construction of the freedom wall. So did two other members. One chose not to vote, and the fifth opposed the idea.

Yup. Speech of all types (Jefferson Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression)

“It is a rather courageous thing for a government to get behind — particularly politicians — because this is going to be directly in front of our City Hall,” Mayor Caravati said at the time. “What it’s inviting is speech of all type.”

At public hearings, only two citizens stepped to the microphone to oppose the community chalkboard. They grumbled that plenty of others thought it was a bad idea but didn’t feel they could speak out against free expression in a generally liberal university town such as Charlottesville.

David Toscano, a lawyer and former Charlottesville mayor, was the lone council member to vote against the chalkboard proposal. He said he was not thrilled with the monument’s proposed style and scale. “It’s too big and too modern” for a city that has carefully preserved a colonial look, he said at the time.

The nature of the structure being built may lend itself more to being a graffiti board than a monument to the First Amendment. It will take a lot of public resources to manage what might end up being a rather chaotic scene, right in front of City Hall.

Toscano also said he feared that the wall would be a magnet for confrontation. “What will happen if a racial hate group decides it wants to adopt that board and just put up racial epithets on a daily basis?” he worried.

Creativity comes in all forms and sizes. (Jefferson Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression)

Most of the people I’ve talked with in Charlottesville tell me that in the years since the Freedom of Expression Monument finally rose in 2006, there have indeed been a few sexually graphic drawings, some homophobic and teenage-angst “Joe loves Sally” messages, and some of what many observers would charitably call graffiti “art” mixed in with well-thought-out points of view.

But no confrontations of any note.

“I don’t think any minority person in this country is going to be surprised that there is in fact racism in our country,” Josh Wheeler, Jefferson Center’s former associate director (and its new director as of April), remarked shortly after the Freedom of Expression Monument was approved. “They may in fact be surprised to see how many people don’t agree with that kind of view. And so I think the monument will serve a very positive function, even when some speech is offensive.”

Most observers I’ve talked with since say the people in Thomas Jefferson’s town know the difference between smaller message boards, where people advertise rooms for rent and stick up notices about political gatherings, and a monument to freedom. Rude, crude, and otherwise offensive content, while part of the mélange of messages, doesn’t stay in view too long. It disappears when the board is erased and washed by Jefferson Center workers, but those who find it unpalatable sometimes walk up and erase it themselves.

That’s free expression, too, the monument’s supporters say.

One of the surprising aspects of the community chalkboard, in the eyes of some observers, is the city’s pledge that no Charlottesville official — not the mayor, not a police officer, not a maintenance worker — will touch the board in an official capacity.

Except for one incident in which a new city manager ordered something wiped clean, that agreement has by all accounts been kept.

The folks at the Jefferson Center and others assumed that there’d be a lot of interest in the monument for the first six months or so. Then, they worried, it would sit virtually empty of messages and become an eyesore.

Sometimes people go on and on with their chalk because they feel strongly about what they're writing. (Jefferson Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression)

“Oh no,” Josh Wheeler told me this week. “It fills up to the point that there’s hardly space to write. Yet people do anyway, even if you can’t really read what they’re saying. It’s not a whim. It’s as if they have a real need to express themselves. Sometimes we have to clean the board two or three times a week. Someone we’ll have cleaned one side and be working on the other, and people come up and start writing on the clean side while it’s still damp.”

I asked him if the monument has meant something beyond its function as a place to vent.

“It’s brought a lot of attention to Charlottesville as a center for free expression,” he said. “It’s been a connection between the public and nonprofit organizations doing good works — shelters, advocates for the homeless, that sort of thing. And it’s been a place where our community can come together, as in the days after the Virginia Tech shooting, when people by the hundreds stepped forward to express condolences.”

Peter O'Shea, one of the designers of the Freedom Wall, drew this tribute to the Virginia Tech shooting victims. (Jefferson Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression)

He’s referring to the 2007 massacre of 32 people and wounding of 25 others by an international student enrolled at the university down the road in southwest Virginia, which, incidentally, is the University of Virginia’s biggest rival.

I regret that I was not on hand to ask the two Egyptian women what they were thinking when they wrote their nation’s name in English, drew the figure of a bright sun, and added other messages that the photo does not capture. I do know from Barbara Drinkwater, one of their Friendship Force hosts in Charlottesville, that the women told her they would take the free-expression chalkboard idea back to Cairo.

And I wonder what I might write there, if anything, the next time I’m in Charlottesville.

What would you write?

A message for the season! (Jefferson Center for the Protection of Freedom of Expression)